(单词翻译:单击)

听力文本

This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Christopher Intagliata.

In 1947 the Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl set sail from Peru on a balsa wood raft called Kon-Tiki. As he explained a few years later in the documentary of the same name, Heyerdahl was convinced that Indigenous people from South America had used a similar craft to settle Polynesia.

(CLIP: "The only way to test my theory was to build one of these rafts, launch it into the sea off the coast of Peru, and find out if wind and current would, in fact, waft us ashore on South Pacific islands.")

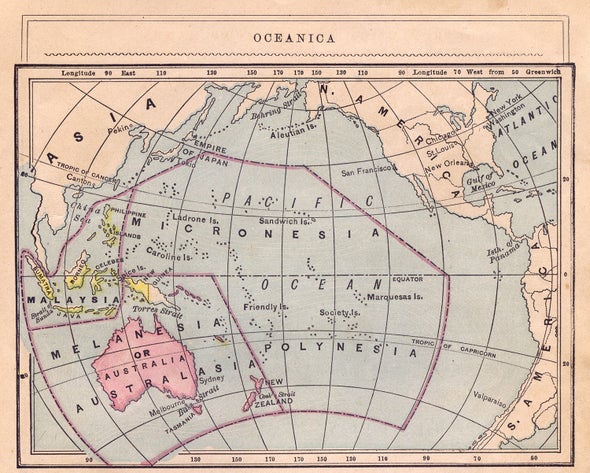

One hundred one days and 4,300 nautical miles later, his raft reached French Polynesia. The expedition didn't really prove anything other than that the feat was possible. And most scholars agreed then and now that the Pacific islands were gradually settled from the other direction, by people traveling from East Asia.

But a new study suggests that almost 900 years ago, Polynesians and Native South Americans did make contact—and traces of that encounter live on in the genes of Polynesians today.

"Whether the people were physically standing on an island in Polynesia when they began mingling—or whether they were on the coast of South America—we can't say."

Alex Ioannidis, a computational scientist and geneticist at Stanford University. His team compared the DNA of 800 individuals from 17 Pacific islands and 15 Pacific Coast Native American groups. And they discovered, within the genomes of modern-day Polynesians, snippets of DNA typically found in Native Americans.

"What we found is: it's actually a very similar sequence of DNA that they all share. That's not explained otherwise than having a common ancestor in recent times."

That ancestor likely came from the region of present-day Colombia or Ecuador, says co-author Andrés Moreno-Estrada of Mexico's National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity. And the similarity of that sequence across Polynesians suggests only a single contact occurred. Based on the lengths of those DNA segments in modern individuals, the scientists were able to pin a possible date on the meeting: around the year 1150.

The study is in the journal Nature.

It's important to note that while the finding does imply the two cultures met, it doesn't say anything about which culture initiated the contact. And it certainly doesn't support Heyerdahl's controversial theory that Polynesian culture derives from settlers from South America.

However, Ioannidis points out that the discovery aligns with some nongenetic observations. For example, the sweet potato—a South American crop—is found in Polynesia, but how it got there is less clear. This study could provide an explanation.

"The other interesting thing about the sweet potato is the word used for it in some of the Polynesian languages is very close to the word used for it in some of the northwestern South American languages. And that's something that has been noticed before people pointed it out. And I think, you know, it's very interesting, given the results we found."

Moreno-Estrada says the findings are valuable to anthropologists, but his primary interest was relaying the results back to the Polynesians who took part in the study.

"They were really excited, knowing about their own history and getting a picture of really what has been preserved in the DNA, in respect to their ancestors."

Thanks for listening for Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

参考译文

这里是科学美国人——60秒科学系列,我是克里斯托弗·因塔格里塔。

1947年,挪威探险家托尔·海尔达尔乘坐“康提基号”轻木筏从秘鲁启航。正如他几年后在同名纪录片中所解释的那样,海尔达尔确信南美土著人就是乘坐类似的木筏到波利尼西亚定居的。

(音频片段:“检验我的理论的唯一方法是建造这样一个木筏,让其在秘鲁沿海海域启航,并确定风和水流是否会将我们吹向南太平洋群岛岸上。”)

在历时101天、航行4300海里之后,他的木筏到达了法属波利尼西亚。这次探险没有证明其他事情,只证明了这项壮举是可能的。当时和现在的大多数学者都认为,逐渐在太平洋岛屿定居的是来自另一个方向的东亚人。

但一项新研究表明,近900年前,波利尼西亚人和南美土著人确实确实有过接触,那次相遇的痕迹如今还存在于波利尼西亚人的基因中。

“无论这些人接触时是站在波利尼西亚某岛屿上,还是身处南美洲海岸,我们都说不清。”

斯坦福大学的计算科学家和遗传学家亚历克斯·伊安尼迪斯说到。他的研究团队比较了来自17个太平洋岛屿和15个太平洋沿岸美洲土著群体的800名个体的DNA。他们发现,现代波利尼西亚人的基因组中常常会发现美洲土著人的DNA片段。

“我们发现:这是一个二者共享的非常相似的DNA序列。这只能说明二者近代的祖先相同。”

该研究的共同作者、墨西哥生物多样性基因组学国家研究室的安德烈斯·莫雷诺-埃斯特拉达表示,这位祖先可能来自如今的哥伦比亚或厄瓜多尔。而在波利尼西亚人之间,这一序列的相似性表明只发生了一次接触。根据现代个体中这些DNA片段的长度,科学家能够确定那次见面可能发生的日期:大约在1150年。

这项研究发表在《自然》期刊上。

值得注意的是,虽然这一发现确实暗示两种文化相遇,但并没有说明哪种文化发起了这种接触。当然,这项研究也不支持海尔达尔具有争议的理论,即波利尼西亚文化起源于南美移民。

然而,伊安尼迪斯指出,这一发现与某些非基因观察结果一致。例如,人们在波利尼西亚发现了一种南美作物——甘薯,但它如何到达该地的尚不清楚。本研究可以提供一种解释。

“有关甘薯的另一个有趣的事是,波利尼西亚某些语言中‘甘薯’的发音,与南美洲西北部某些语言的发音非常相似。在被指出之前,人们就已经注意到了这一点。基于我们的研究结果,我认为这很有趣。”

莫雷诺·埃斯特拉达表示,这些发现对人类学家来说很有价值,但他主要感兴趣的是将研究结果转告参与这项研究的波利尼西亚人。

“他们真的很兴奋,因为他们了解了自己的历史,还知道了自已DNA中至今保留着与祖先有关的东西。”

谢谢大家收听科学美国人——60秒科学。我是克里斯托弗·因塔利亚塔。

译文为可可英语翻译,未经授权请勿转载!

重点讲解

重点讲解:

1. set sail 启航;开船;

He loaded his vessel with another cargo and set sail.

他给自己的船装上另一批货后便启航了。

2. derive from (使)起源于;(使)来自;

Their numerical system, derived from the Babylonians, was based on multiples of the number six.

他们的数制源自古巴比伦人,以数字6的倍数为基数。

3. be close to 近的;接近的;

The children are close to each other in age.

这些儿童彼此的年龄很接近。

4. take part in 参加;参与;

Six theatre companies have been selected to take part in this year's festival.

已选定六个剧团参加今年的戏剧节。