(单词翻译:单击)

听力文本

This is Scientific American's 60-second Science, I'm Eliene Augenbraun.

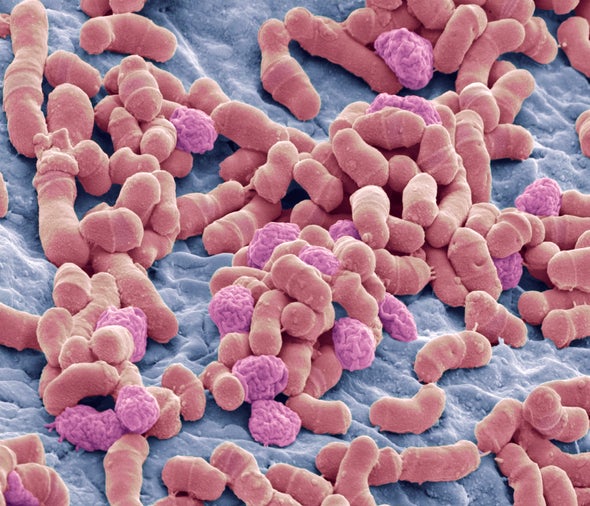

Our microbiomes—the tiny organisms that live on us and in us—can influence our health. And a recent study looked at microbiome composition and diversity, depending on where and how we live, given the same latitude and climate across South America:

"We found, in a gradient of urbanization from jungle houses, huts of Amerindian people living traditional lifestyles, all the way to a modern city like Manaus, was differences in microbes from our houses and from our skin and differences in exposure to chemicals."

Microbiologist Maria Gloria Dominguez Bello from Rutgers University.

She and her colleagues collected samples from people, pets and spaces in homes like the kitchen, bathroom and bedrooms. They analyzed bacteria, fungi, parasites and chemicals. And they found two trends as you go from the rain forest to a farm to a town to the city of Manaus. With increasing population density:

"We are exposed to a higher diversity of fungi. We carry more diversity of fungi in our skin, but in our gut, we lose microbial diversity."

The study is in the journal Nature Microbiology.

Urban homes use more chemical cleaners than do rural or rain forest homes. And they're more likely to be built out of synthetic materials. So city residents are burdened with more chemicals, including metabolites of cleaners, detergents and paints, in and on their bodies.

In addition, the microbes of urban dwellers are far more like each other than they are like the more healthful mix found in the rain forest. Dominguez Bello thinks one reason is that we are too isolated from natural landscapes.

"We have grown, culturally, very anti-dirt. We call dirt 'dirt' and, you know—we call the soil 'dirt,' and that already has a connotation of undesirable."

Perhaps city living could be a bit healthier with fewer chemicals from cleansers and more microbes from what gets cleaned.

For Scientific American's 60-second Science. I'm Eliene Augenbraun.

参考译文

这里是科学美国人――60秒科学系列,我是艾琳·奥根布劳恩。

我们的微生物群——生活在我们体外和体内的微型有机体——可以影响我们的健康。最近的一项研究着眼于微生物群落的组成以及多样性因人类居住地点和生活方式不同而产生的差异,考虑到整个南美的纬度和气候相同:

“我们发现,从过着传统生活的美洲印第安人的丛林住宅和小屋,一直到马瑙斯这样的现代化城市,由于城市化进程存在不同,我们的房屋内和皮肤中的微生物有所差别,我们接触的化学物质也存在差异。”

罗格斯大学的微生物学家玛丽亚·格洛丽亚·多明格斯·贝洛说到。

她和同事从人类、宠物以及厨房、浴室和卧室等家里的空间收集样本。他们分析了细菌、真菌、寄生虫和化学物质。他们发现,从雨林到农场、城镇再到马瑙斯市,结果显示有两种趋势。随着人口密度的增加:

“我们接触的真菌种类越来越多。我们的皮肤携带的真菌种类也在增加,但肠道内的微生物多样性在下降。”

这项研究发表在《自然·微生物学》期刊上。

城市家庭使用的化学清洁剂比乡村或雨林家庭要多。这些清洁剂很有可能是合成材料制成的。因此,城市居民更多地承受化学物质之苦,包括我们体内外的清洁剂、去污剂和涂料和涂料的代谢产物。

此外,与雨林居民身上更健康的微生物组合相比,城市居民的微生物彼此之间的相似性要高得多。多明格斯·贝洛认为原因之一是我们太孤立于自然景观。

“从文化角度看,我们变得非常‘抗拒土’。我们将土称为‘土’,将土壤也称为‘土’,而‘土’已经包含了不受欢迎的含义。

或许制造清洁剂时可以少用些化学物质,多用些微生物,这样城市生活会变得更加健康。

谢谢大家收听科学美国人——60秒科学。我是艾琳·奥根布劳恩。

译文为可可英语翻译,未经授权请勿转载!

重点讲解

重点讲解:

1. look at (尤指专家)检查,察看;

We have set up a task force to look at the question of women returning to work.

我们已经成立了一个工作组去调查妇女复工的问题。

2. depend on 取决(于);有赖(于);

The risk and severity of sunburn depend on the body's natural skin colour.

晒伤的风险和严重程度取决于人体的自然肤色。

3. be exposed to 使暴露于(险境);使遭受(危险或不快);

They had not been exposed to most diseases common to urban populations.

城市人口中多数常见的疾病他们都没有接触到。

4. in addition 另外;加之;除…之外;

Part-time English classes are offered. In addition, students can take classes in word-processing and computing.

开设了非全日制的英语班。另外,学生可以修读文字处理和计算机课程。