(单词翻译:单击)

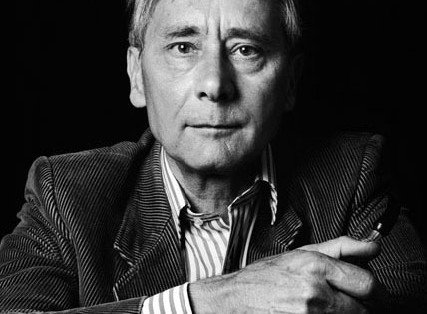

Obituary;Alan Sillitoe

讣告;艾伦·西利托

Alan Sillitoe, writer, died on April 25th, aged 82

英国作家艾伦·西利托于2010年4月25日辞世,享年82岁

English working men had been heard from before. Piers Plowman, chancing one summer day upon a field of folk; John Clare's shepherd, observing cabbage fields and nesting birds; D.H. Lawrence's taciturn miners, washing off their grime before the fire. But the toiler on the assembly line had never spoken up so loudly until Alan Sillitoe, in “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” (1958), produced Arthur Seaton.

英国劳动者的文学形象以前便出现过:皮尔斯·普洛曼曾在某个夏日与一群田野莽夫不期而遇;约翰·克莱尔笔下的牧羊人会耐心观察卷心菜地和筑巢的飞鸟;D·H·劳伦斯描述的那些沉默寡言的矿工则会在炉火前洗掉他们身上的污垢。但是,这些生产线上的人物形象从未发出过多响亮的声音。直到艾伦·西利托于1958年写出小说《周六晚和周日晨》——主人公亚瑟·西顿的诞生才宣告终结这种局面。

Twenty-one-year-old Arthur, between chamfering and drilling to produce 1,400 parts a day at the Raleigh bicycle factory in Nottingham (“Forty-five bob don't grow on trees”), led a life of rampant cuckoldry with Brenda (“so lush and loving”) in Strelley Woods. “Time flies and no mistake,” sighed Arthur,

二十一岁的亚瑟终日劳作于诺丁汉Raleigh自行车厂的倒棱和钻孔车床间,每天可生产1400个零件(“45先令可不大好挣”)。而在斯特雷利伍兹,他又过着与有夫之妇布伦达(“如此性感深情”)私通的浪荡生活。“时间真是过得飞快,”亚瑟叹道

and it's about time it did because I've done another two hundred and I'm ready to go home and get some snap and read the Daily Mirror or look at what's left of the bathing tarts in the Weekend Mail. But Brenda, I can't wait to get at her…And now this chamfer-blade wants sharpening.

总算是过去了,瞧我又做了200个(零件),正要回家呢,来点脆饼,读下《每日镜报》,没准还能瞅瞅《周末邮报》上那帮泡澡的骚娘们儿。但是,布伦达,我的美人儿,我可是急着要去见她……现在倒好,这块倒角刀片还得磨快点。

This cocky bastard, soon personified in film by Albert Finney, gave English society a shock, besides its first full description of a backstreet abortion with hot gin and boiling bath-water. But Mr Sillitoe spoke too, in the voice of Smith in “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner” (1959), for the petty-criminal underclass, Borstal boys:

不久,这个自以为是的浑蛋就被搬上荧幕,由艾伯特·芬尼担纲主演。亚瑟的出现带给英国社会一次强烈的震撼,小说还首次完整描述了那种借助辛辣的杜松子酒与滚烫的洗澡水而非法堕胎的过程。而在1959年创作的小说《一名长跑运动员的孤独》中,作家借主人公史密斯之口也为那些轻微犯罪的草根阶层——教养院男孩发言:

I didn't think about anything at all, because I never do when I'm busy, when I'm draining pipes, looting sacks, yaling locks, lifting latches, forcing my bony hands and lanky legs into making something move, hardly feeling my lungs going in-whiff and out-whaff…When I'm wondering what's the best way to get a window open or how to force a door, how can I be thinking?

我根本不去考虑任何事,因为当我忙个不停,当我在弄排水管,在偷面粉袋,在撬锁,在拉插销,在强迫我瘦骨嶙峋的双手配合细长的双腿一起挪开东西,在几乎感觉不到我的肺是在吸气还是在呼气的时候,我是从不会走神的……当我正寻思着这世上有没有什么能凿开窗户或打开房门之类的完美诀窍时,你教我如何去想别的?

Mr Sillitoe gave voices and identities to the street-crowds of post-war Britain, working in industries that were already dying, living for football and televisions on the never-never and Saturday-night binges in which pints of ale led rapidly to a fist in the face and the cold, hard pavement. Standing at the lathe as Mr Sillitoe had stood, they dreamed of “marvellous things”.

西利托为战后英国那些街头游民注入了血肉和灵魂。这些人在濒临死亡的产业中艰难求存,为足球和分期付款才能买到的电视而活,为周六夜晚的短暂狂欢而活——他们灌下数品脱的麦芽啤酒过后便能迅速导致一场殴斗,拳头会落在脸上,人就会躺在僵冷的路上。如同西利托往日那样,站在车床旁边的他们也会梦想着那些“绝妙的事物”。

And they would not kowtow to anyone, whether rate-checker, foreman, boss or government. They dreamed—if they could get the whip hand, which they never would—of blowing all these boggers sky-high with dynamite, or sticking them up against a wall. It was not a communist thing. Mr Sillitoe was feted in the Soviet Union, but carried back an image of heartless chaos. Capitalism and communism both robbed a man of freedom. Mr Sillitoe's heroes defied all systems and were part of no class, except “us” versus “them”. They kept their own pride, like Seaton's sharp suits for a big night out, or the exhilaration Smith felt, “like the first and last man on the world”, when he ran through the fields alone, and wouldn't pander to the Borstal governor by winning a race for him. “It's a fine life, if you don't weaken,” was one Sillitoe motto. Another was “Don't let the bastards grind you down.”

然而他们不会屈服于任何人,无论对方是评级员、工头、老板还是政府。他们梦想着——假如他们能出人头地……事实上这不大可能——用黄色炸药将这些杂碎统统炸到天上,或是将他们戳在墙上抽几鞭子。这并非共产主义者的阶级仇恨。苏联曾热情款待过西氏,可他回想的却是那无情的混乱。资本主义与共产主义双双劫掠了人的自由。因而,西氏笔下的主人公反抗所有的体制权威,除了用“我们”PK“他们”来形容之外,这些“英雄”不属于任何阶级。他们的个性是骄傲的,犹如西顿身上很潮的服饰适合于意义重大的节日之夜,犹如史密斯所感到的亢奋激动那样——当他独自跑着穿越田野,违背教养院院长令其为他夺冠的意志时,他觉得自己“就像第一个和最后一个在这世上的人”。“你若坚强,生活就美好”恰是西氏的一句座右铭。另一句则是“别让那些杂碎整垮你”。

Mapping out the world

规划人生

Writers about the poor tended to be middle-class patronisers. But Mr Sillitoe was a product of those sooty red-brick terraces, where he remembered his mother, beaten yet again by his father, holding her head over a bucket so the blood didn't run on the carpet; where he would forage in tips for bottles to claim the deposit, or pick flowers from the park to sell. At 14 he became a labourer and lathe-operator, as well as a serial lover of the local girls.

以穷人为写作对象的作家常会摆出一副中产者高人一等的样子。西氏却不同,他本人即是那种已被煤烟熏个乌黑的红砖排房所产的“一件产品”,他仍记得,就在这儿,被父亲反复殴打的母亲把头架在桶边好让血别流到毯子上;还是在这儿,他会钻进垃圾堆里找瓶子而讨要押金,或是从公园那头折些花儿来贩卖。十四岁时,西利托成长为一名车工兼户外蓝领,同时也与当地多名女孩保持恋情。

His father was illiterate, unable to make sense of the “mystifying jungle” of the world. Hence his violence. Young Alan mapped out his own paths, first in out-of-town fields through nettles as tall as himself, and then by slowly building up exotic worlds of words. He won a Bible as a prize, which stayed on his desk for good; more books, and maps, were bought with precious pence, or came home under his coat. Confinement with TB in his 20s introduced him to Dickens and Dostoevsky, Balzac and Plato, and spurred him to write. Both writing and exploring kept him one cool, cunning step ahead of his oppressors. If he could not do either, he felt his head would burst from sheer misery.

他的父亲是个文盲,无法理解这世界“令人困惑的丛林”意义,因而迷信暴力。年青的艾伦起先在长得跟他一样高的荨麻地里“精心”规划着人生,后来便慢慢用词语搭建起绚烂的奇异世界。有人奖赏他一本《圣经》,此物却一直搁在他的书桌上。少的可怜的便士被他用来买书和地图,兴许他还会将这些东西偷偷藏进外套再带回家。到二十多岁,因身患肺结核,他卧床阅读狄更斯、陀思妥耶夫斯基、巴尔扎克和柏拉图,并由此激发了写作欲。似乎创作和考察让他在压迫者面前保持冷静、狡黠。倘若不去做这些,西氏便觉得自己的头要在全然的痛苦中爆掉了。

He wrote, then, prodigiously, for half a century: novels, short stories, poetry, autobiography. The poems were feeble, and the stories that followed his two groundbreaking works tended to tell, less well, the same tale of Everyman against the system. Though he had started “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” under an olive tree in Majorca, and lived many years in the Mediterranean sun, he needed Nottingham, and the pounding roar of the Raleigh factory. Occasionally he wandered back, but settling was difficult. He came to sympathise, over the years, as much with the world's displaced and hounded Jews as with his drunken proletarian heroes.

此后,西利托爆发出惊人的能量,写作生涯长达半个世纪,涉及长篇小说、短篇小说、诗歌和自传。他的诗未免虚弱乏力。而继前期两部开创性作品之后的短篇也乏善可陈,因为未能推陈出新,题材往往是讲述普罗大众与体制作斗争的老套故事。西氏曾在西班牙马略卡岛的一株油橄榄树下开始构思《周六晚和周日晨》,亦在地中海地区生活了多年,即便如此,他依然需要诺丁汉,需要Raleigh车厂里面洪亮的金属撞击声。偶尔,他会回来转转,但要定居则很难。对于笔下喝得烂醉的无产阶级主人公,西氏多年来所抱有的同情与他对待那些流离失所、时常遭受袭扰的犹太人时的感情其实并无二致。

Alongside the “Angry Young Men” of post-war literary Britain—Kingsley Amis, John Osborne and the rest—he cut a different figure. It was not the constant pipe, or the Nottingham vowels, or the friendly but disconcerting stare. It was his refusal to be labelled as angry, or as anything else, and his indifference to literary acclaim. His books could sink or swim. He had his own worth, and his own pride. As Arthur Seaton put it, “He was nothing at all when people tried to tell him what he was.”

相较英国战后那些“愤怒青年”作家——比如金斯利·埃米斯、约翰·奥斯本和他人而言,西利托显得卓尔不群。这份独特,和那一成不变的烟斗无关,和那一口诺丁汉腔的乡音无关,也和他那友善却令人尴尬的眼神无关。不妨说,西氏的特色乃在于两点:一是他拒绝被外界贴上“愤怒派”或其他流派的标签;二是对于圈内对其作品的褒扬,他漠不关心。他的书可以自己去闯。他有他的价值,也有他自己的骄傲。就像书中人亚瑟·西顿说的那样:“若还要人们去告诉他他是什么时, 那么此人连狗屁都不是了。”