(单词翻译:单击)

Science and technology.

科技。

Moral philosophy.

道德哲学。

Goodness has nothing to do with it.

无关善恶。

Utilitarians are not nice people.

功利主义者并不是好人。

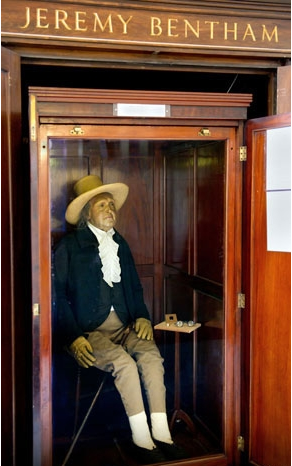

IN THE grand scheme of things Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill are normally thought of as good guys. Between them, they came up with the ethical theory known as utilitarianism. The goal of this theory is encapsulated in Bentham's aphorism that "the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation."

从历史洪流的角度来看,杰里米·贝萨姆和约翰·斯图阿特·密尔通常都被认为是好人。他们一起合作建立了现在被称为功利主义的道德理论。该理论的核心目的可以被贝萨姆的一句格言很好地概括"道德和立法的基础在于让最多的人最大程度的幸福"

Which all sounds fine and dandy until you start applying it to particular cases. A utilitarian, for example, might approve of the occasional torture of suspected terrorists-for the greater happiness of everyone else, you understand. That type of observation has led Daniel Bartels at Columbia University and David Pizarro at Cornell to ask what sort of people actually do have a utilitarian outlook on life. Their answers, just published in Cognition, are not comfortable.

听上去很不错,但当你开始把这套理论应用在具体事件上时问题就出来了。比方说,功利主义者可能赞成对恐怖主义疑犯用刑。大家都明白,这是为了其它所有人好。哥伦比亚大学的丹尼尔·巴特尔斯和康奈尔大学的大卫·皮扎罗受到类似这样的观察启发,提出了哪一类型的人对生活的看法最接近功利主义这一有趣问题。他们的论文最近在认知科学上发表,其中得到的结论让人不安。

One of the classic techniques used to measure a person's willingness to behave in a utilitarian way is known as trolleyology. The subject of the study is challenged with thought experiments involving a runaway railway trolley or train carriage. All involve choices, each of which leads to people's deaths. For example: there are five railway workmen in the path of a runaway carriage. The men will surely be killed unless the subject of the experiment, a bystander in the story, does something. The subject is told he is on a bridge over the tracks. Next to him is a big, heavy stranger. The subject is informed that his own body would be too light to stop the train, but that if he pushes the stranger onto the tracks, the stranger's large body will stop the train and save the five lives. That, unfortunately, would kill the stranger.

测量一个人有多大的意愿以功利主义方式行事的一个传统方法是电车实验。参加者进行一个想象实验,实验里有一节失控的有轨电车或火车车厢。该实验有很多版本,不管哪一个都要求参加者进行选择,而且不管怎么选都会有人死亡。例如:有五个工人在失控车厢前方的轨道上。如果实验参加者作为故事中的一个旁观者不进行干涉这五个人就死定了。参加者被告知他在铁道上方的一座桥上,身边有一个身材肥胖的陌生人,同时参加者知道自己的体重太轻,无法停止火车,但如果把那个陌生人推下去,他的巨大身躯将会停止火车,让五个工人得救。不幸的是这么做会杀死该陌生人。

Dr Bartels and Dr Pizarro knew from previous research that around 90% of people refuse the utilitarian act of killing one individual to save five. What no one had previously inquired about, though, was the nature of the remaining 10%.

巴特尔斯博士和皮扎罗博士从之前的研究中得知大约90%的参加者会拒绝杀死一个陌生人救出五个人的功利主义行为。但是之前的研究没人提出过剩下的10%人的性格这一问题。

To find out, the two researchers gave 208 undergraduates a battery of trolleyological tests and measured, on a four-point scale, how utilitarian their responses were. Participants were also asked to respond to a series of statements intended to get a sense of their individual psychologies. These statements included, "I like to see fist fights", "The best way to handle people is to tell them what they want to hear", and "When you really think about it, life is not worth the effort of getting up in the morning". Each was asked to indicate, for each statement, where his views lay on a continuum that had "strongly agree" at one end and "strongly disagree" at the other. These statements, and others like them, were designed to measure, respectively, psychopathy, Machiavellianism and a person's sense of how meaningful life is.

为了找出结果,这两个研究者对208个大学生进行了一系列电车实验,并以一到四分的机制来给他们的答案中的功利主义成分打分。参加者也要进行一系列分析个人心理的测试。测试包括这些问题,"我喜欢看人打架","应付别人最好的办法就是说他们想听的话",以及"认真想想的话,生活没什么意思,每天起来真不值"。参加者要在一个连续的尺度上标出他们对每一个问题的看法,从"完全同意"到"完全不同意"。这三个问题按次序分别是为了测量一个人的冷血程度,厚黑程度以及他觉得生活是否有意义的程度,其它问题也是围绕着测量这三个方面而设计的。

Dr Bartels and Dr Pizarro then correlated the results from the trolleyology with those from the personality tests. They found a strong link between utilitarian answers to moral dilemmas (push the fat guy off the bridge) and personalities that were psychopathic, Machiavellian or tended to view life as meaningless. Utilitarians, this suggests, may add to the sum of human happiness, but they are not very happy people themselves.

巴特尔斯博士和皮扎罗博士然后开始寻找人格测试和电车实验结果的相关性。他们发现在面对道德两难(将胖子推下去)时回答体现功利主义的参加者和冷血变态心理,厚黑主义以及觉得生活没意义的想法有很强的关联。这表示虽然功利主义者能够增加人类整体的幸福值,但他们自己并不是什么快乐的人。

That does not make utilitarianism wrong. Crafting legislation-one of the main things that Bentham and Mill wanted to improve-inevitably involves riding roughshod over someone's interests. Utilitarianism provides a plausible framework for deciding who should get trampled. The results obtained by Dr Bartels and Dr Pizarro do, though, raise questions about the type of people who you want making the laws. Psychopathic, Machiavellian misanthropes? Apparently, yes.

这并不意味着功利主义是错误的。任何法律的制定-当年贝萨姆和密尔希望借其理论能够有所助益的主要行为之一-不可避免的需要牺牲一部分人的利益。功利主义提供了一个比较合理的框架来决定应该牺牲谁的利益。不过巴特尔斯博士和皮扎罗博士的研究提出了应该让哪种人来制定法律的质疑。冷血,厚黑的厌恶人类者?从表面上来看,是的。