(单词翻译:单击)

听力文本

This is Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

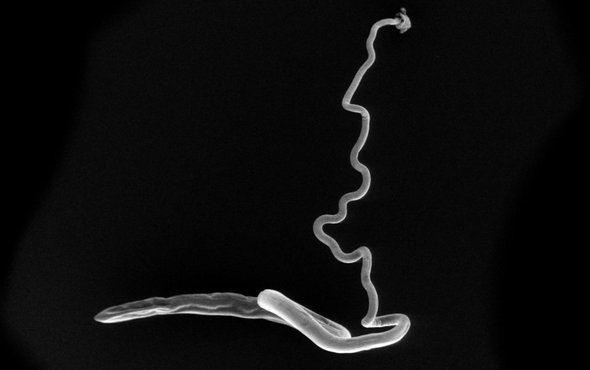

The whipworm is a parasite that infects half a billion people around the world. It lives in the gut—burying its head in the large intestine, causing symptoms like nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhea.

But the worm's place of residence also reveals a potential weakness: the parasite needs to steal some of our own gut bacteria to thrive.

"It takes them from the host and then bends it to generate a population which suits itself." Richard Grencis, an immunoparasitologist at the University of Manchester in the U.K. "So if they have bacteria, then they survive, if they don't have bacteria, they don't survive."

Grencis and his team studied that phenomenon in mice—because there's a type of whipworm adapted to them too. And they found that when whipworms hatch, they acquire a fresh microbiome derived from the host's own microbiome, but with different proportions of species. Without that host contribution, the worms die.

But the worms also induce changes in the host's microbiome—tweaking it so the gut is no longer hospitable to hatching.

"Now you'd have to ask, well, that seems a little bit paradoxical, because maybe the parasite wants to have more rabbit establishing rather than less." But here's the catch: Go on a hatching spree, and the host's immune system is going to take notice, and kick all the worms out.

"If the eggs don't hatch as effectively, because parasites of the gut, you don't get as many new worms coming in, so you delay the process of host immunity being acquired and then expelling the parasites. So it's a strategy that might have evolved to help perpetuate the life of the parasite, so it could stay there a bit longer."

The results are in the journal Science Advances.

Grencis says the findings might someday lead to a way to selectively target the worms. So that whipworms no longer mooch off us—or our microbes.

Thanks for listening for Scientific American — 60-Second Science. I'm Christopher Intagliata.

参考译文

这里是科学美国人——60秒科学。我是克里斯托弗·因塔利亚塔。

鞭虫是令全球5亿人感染的一种寄生虫。它寄生在我们的肠道中,它将头埋进大肠里,可引发恶心、腹痛和腹泻等症状。

但是鞭虫的寄居地也暴露了其潜在的弱点:为了茁壮成长,寄生虫需要偷取人类的肠道细菌。

“鞭虫从宿主身上获得细菌,使其产生适合自己的菌群。”英国曼彻斯特大学的免疫寄生虫学家理查德·格兰西斯说到。“如果它们获得了细菌,那它们就能存活下来,如果它们没有得到细菌,那它们就无法存活。”

格兰西斯和团队在老鼠身上研究了这种现象,因为老鼠体内也有适应其生存的一种鞭虫。他们发现,鞭虫孵化时会从宿主的菌群中获取新鲜的菌群,不过各种细菌的比例与宿主的不同。没有宿主的细菌贡献,鞭虫就会死亡。

但是鞭虫也会诱发宿主体内菌群的变化——对菌群进行调整,使宿主肠道不再适合鞭虫孵化。

“现在你不禁要发问,这似乎有点矛盾,寄生虫不是应该希望繁殖更多后代,而不是减少后代数量吗?”但是要注意:无节制地进行孵化,会引起宿主免疫系统的注意,然后将所有鞭虫清除出去。

如果因为肠道寄生虫而导致虫卵无法有效孵化,那肠道内就不会产生很多新虫子,这样一来就会延缓宿主获得免疫的进程和清除寄生虫的过程。因此,这可能是进化出来的一种策略,帮助寄生虫延续生命,让其在肠道内待的时间更长一些。

这项研究结果发表在《科学进展》期刊上。

格兰西斯表示,这一发现可能在未来会发展出选择性清除鞭虫的方式。因此,鞭虫再也不能从我们——或者说我们的细菌中——揩油了。

谢谢大家收听科学美国人——60秒科学。我是克里斯托弗·因塔利亚塔。

译文为可可英语翻译,未经授权请勿转载!

重点讲解

重点讲解:

1. adapt to 适应;

In order to adapt to the development and innovation, teachers should constantly improve their own professional accomplishments.

教师要适应发展和变革,必须不断提高自身的专业素质。

2. rather than 而非;胜于;而不是;

Much of the food pleases rather than excites.

这些食物中许多只是让人满意,但并不让人兴奋。

3. take notice 注意;关注;

This should make people sit up and take notice.

这件事应引起人们的关注。

4. kick out 强使离开;赶走;

Over the years, Mr Sata has garnered a reputation for populist rhetoric and he has previously said he would kick out bogus investors.

多年来,萨塔以发表民粹主义言论而闻名,他曾表示,他将把假冒投资者赶出去两个来自香港的少年也同样问了自己这个问题,现在他们研发了一种门把手,可以清除在接触过程中产生的细菌。