(单词翻译:单击)

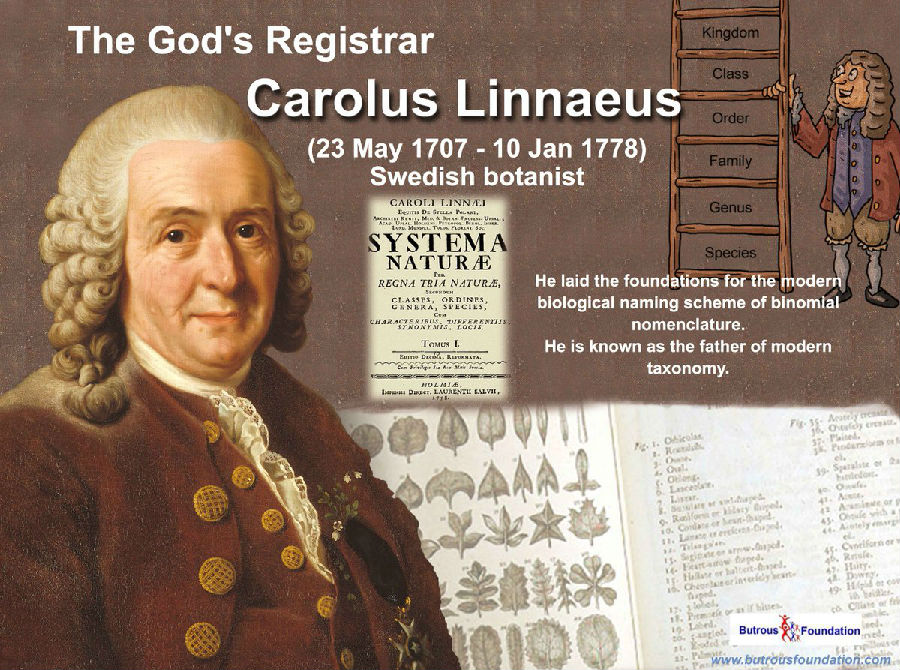

The Linnaean system is so well established that we can hardly imagine an alternative, but before Linnaeus, systems of classification were often highly whimsical. Animals might be categorized by whether they were wild or domesticated, terrestrial or aquatic, large or small, even whether they were thought handsome and noble or of no consequence. Buffon arranged his animals by their utility to man. Anatomical considerations barely came into it. Linnaeus made it his life's work to rectify this deficiency by classifying all that was alive according to its physical attributes. Taxonomy — which is to say the science of classification — has never looked back.

林奈分类系统的地位已经牢固确立,我们很难想像还能有别的体系来取而代之。而在林奈之前,分类体系是极其随意的。动物的分类标准可以是:野的还是家的,陆生的或水生的,大的还是小的,甚至它们被认为是漂亮和高贵的还是无足轻重的。布丰根据动物对人的用途大小来进行分类,几乎不考虑解剖学上的特点。林奈按照生理特征来进行分类,把纠正上述不足作为自己毕生的事业。分类学——即分类的科学——再也没有走回头路。

It all took time, of course. The first edition of his great Systema Naturae in 1735 was just fourteen pages long. But it grew and grew until by the twelfth edition — the last that Linnaeus would live to see — it extended to three volumes and 2,300 pages. In the end he named or recorded some 13,000 species of plant and animal. Other works were more comprehensive — John Ray's three-volume Historia Generalis Plantarum in England, completed a generation earlier, covered no fewer than 18,625 species of plants alone — but what Linnaeus had that no one else could touch were consistency, order, simplicity, and timeliness.

这一切当然都要花时间。他的大作《自然体系》在1735年的第一版只有14页。但是,它越来越长,越来越长,到了第12版——林奈活着见到的最后一版——已经扩展到3卷,长达2300页。最后,他命名或记录了大约13000种植物和动物。别的著作覆盖面还要广泛——约翰·雷在一代人以前完成的3卷本英格兰的《植物通史》仅植物就包括了不少于l8625种——但是,林奈有着没有人可以相比的地方:连贯、有序、简洁、及时。