(单词翻译:单击)

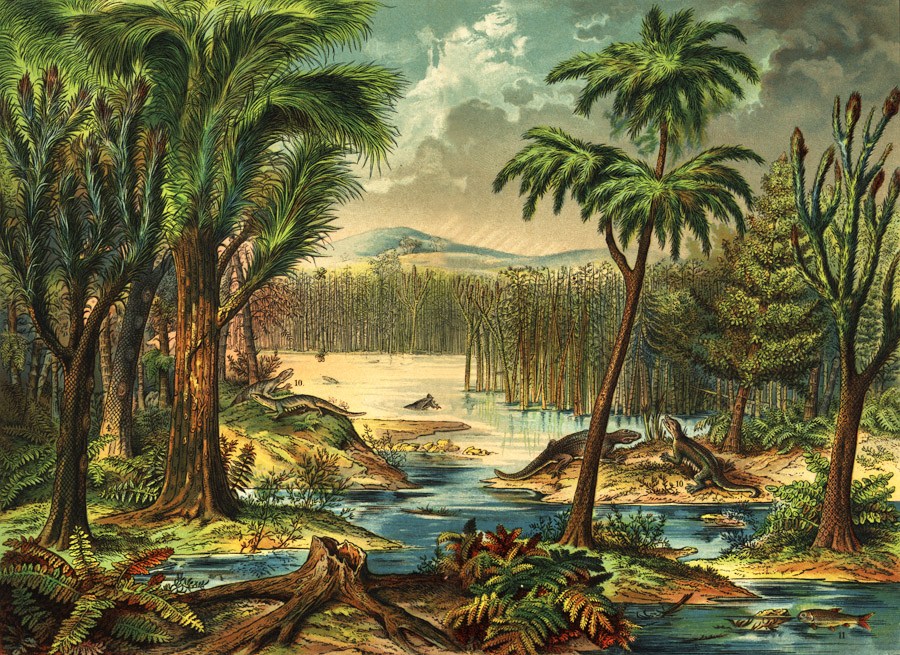

Then, as now, dragonflies could cruise at up to thirty-five miles an hour, instantly stop, hover, fly backwards, and lift far more proportionately than any human flying machine. "The U.S. Air Force," one commentator has written, "has put them in wind tunnels to see how they do it, and despaired." They, too, gorged on the rich air. In Carboniferous forests dragonflies grew as big as ravens. Trees and other vegetation likewise attained outsized proportions. Horsetails and tree ferns grew to heights of fifty feet, club mosses to a hundred and thirty.

当时和现在一样,蜻蜓能以每小时50多公里的速度飞行,能快停,能悬停,能倒飞。要是按照比例的话,蜻蜓能升到的高度比人类的任何飞行器所能达到的要高得多。“美国空军,”有一位评论员写道,“把它们放在风洞里,看看它们是怎么表现的,结果感到望尘莫及。”它们也吞噬浓郁的空气。在石炭纪的森林里,蜻蜓长到大得像乌鸦。树木和别的植物同样长得特别高大,杉叶藻和桫椤长到l5米的高度,石松长到40米的高度。

The first terrestrial vertebrates—which is to say, the first land animals from which we would derive—are something of a mystery. This is partly because of a shortage of relevant fossils, but partly also because of an idiosyncratic Swede named Erik Jarvik whose odd interpretations and secretive manner held back progress on this question for almost half a century. Jarvik was part of a team of Scandinavian scholars who went to Greenland in the 1930s and 1940s looking for fossil fish. In particular they sought lobe-finned fish of the type that presumably were ancestral to us and all other walking creatures, known as tetrapods.

第一批陆地脊椎动物——即我们从其演变而来的第一批陆地动物——在一定程度上还是个谜。部分原因是缺少有关的化石,但也要怪一个名叫埃里克·贾维克的脾气怪癖的瑞典人,他的古怪解释和讳莫如深的表现使这方面的进展延误了差不多半个世纪。贾维克是一个瑞典学者考察小组的成员,他们于20世纪30-40年代来到格陵兰寻找鱼化石。他们尤其要寻找一种叶鳍型鱼。据推测,那种鱼是所谓的四足动物,即我们和其他所有会行走的动物的祖先。

Most animals are tetrapods, and all living tetrapods have one thing in common: four limbs that end in a maximum of five fingers or toes.

大多数动物是四足动物,活着的四足动物都有个共同点:有4肢,每肢的尽头最多有5个指或趾。