(单词翻译:单击)

What was most surprising, however, was that there were so many body designs that had failed to make the cut, so to speak, and left no descendants. Altogether, according to Gould, at least fifteen and perhaps as many as twenty of the Burgess animals belonged to no recognized phylum. (The number soon grew in some popular accounts to as many as one hundred—far more than the Cambridge scientists ever actually claimed.) "The history of life," wrote Gould, "is a story of massive removal followed by differentiation within a few surviving stocks, not the conventional tale of steadily increasing excellence, complexity, and diversity." Evolutionary success, it appeared, was a lottery.

然而,最令人吃惊的是,如此之多的体形,打个比方说,却缺少深度、没有留下后代。据古尔德说,在布尔吉斯动物群当中,总共至少有15种,也许多达20种,不属于任何已经确认的门。(在有的通俗读物中,这个数字很快增加到100种之多——远远超过了剑桥大学的科学家们实际宣布的数字。)“生命史,”古尔德写道,“是一个大规模淘汰的故事,接着是少数幸存的品种的分化,而不是个通常认为的不断优化、不断复杂化、不断多样化的故事。”看来,进化的成功真是像玩彩票。

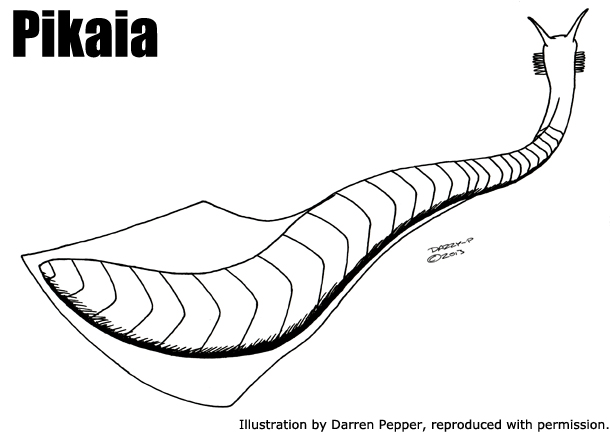

One creature that did manage to slip through, a small wormlike being called Pikaia gracilens, was found to have a primitive spinal column, making it the earliest known ancestor of all later vertebrates, including us. Pikaia were by no means abundant among the Burgess fossils, so goodness knows how close they may have come to extinction. Gould, in a famous quotation, leaves no doubt that he sees our lineal success as a fortunate fluke: "Wind back the tape of life to the early days of the Burgess Shale; let it play again from an identical starting point, and the chance becomes vanishingly small that anything like human intelligence would grace the replay."

然而,有一种动物确实成功地溜过了关。那是一种蠕虫状的小家伙,名叫Pikaia gracilens。据发现,它有一根原始的脊柱,从而成了包括我们在内的所有后来脊椎动物的已知的最早祖先。Pikaia在布尔吉斯化石中根本不多,因此天知道它们是差多么一点儿走向灭绝。吉尔德有一句名言,明确说明他认为我们家系的成功是一件十分侥幸的事:“要是把生命的磁带倒回到布尔吉斯页岩的早期,从同一起点把它再放一遍,任何像人类智慧这样的东西会使其重放异彩的司能性极小。”