(单词翻译:单击)

Physicists are notoriously scornful of scientists from other fields. When the wife of the great Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli left him for a chemist, he was staggered with disbelief. "Had she taken a bullfighter I would have understood," he remarked in wonder to a friend. "But a chemist . . ." It was a feeling Rutherford would have understood. "All science is either physics or stamp collecting," he once said, in a line that has been used many times since. There is a certain engaging irony therefore that when he won the Nobel Prize in 1908, it was in chemistry, not physics.

物理学家特别瞧不起其他领域的科学家。当伟大的奥地利物理学家沃尔夫冈·泡利的妻子离他而去,嫁了个化学家的时候,他吃惊得简直不敢相信。“要是她嫁个斗牛士,我倒还能理解,”他惊讶地对一位朋友说,“可是,嫁个化学家……”卢瑟福能理解这种感情。“科学要么是物理学,要么是集邮。”他有一回说。这句话后来反复被人引用。但是,具有某种讽刺意味的是,他1908年获得的是诺贝尔化学奖,不是物理学奖。

Rutherford was a lucky man—lucky to be a genius, but even luckier to live at a time when physics and chemistry were so exciting and so compatible (his own sentiments notwithstanding). Never again would they quite so comfortably overlap.

卢瑟福是个很幸运的人——很幸运是一位天才;但更幸运的是,他生活在一个物理学和化学如此激动人心而又如此势不两立的年代(且不说他自己的情感)。这两门学科再也不会像从前那样重合在一起了。

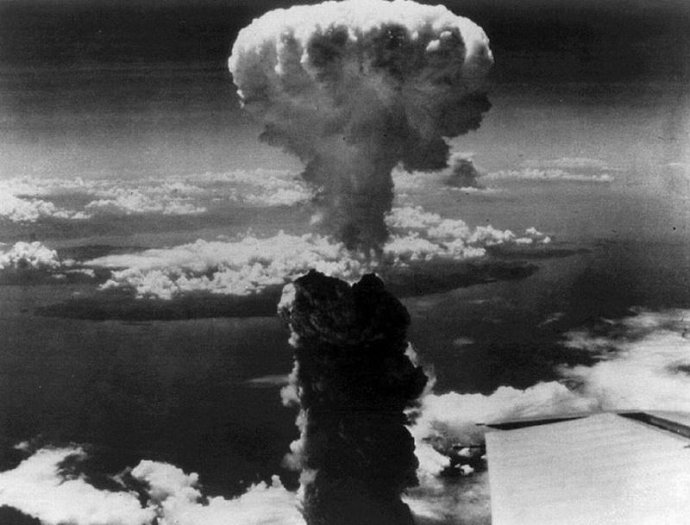

For all his success, Rutherford was not an especially brilliant man and was actually pretty terrible at mathematics. Often during lectures he would get so lost in his own equations that he would give up halfway through and tell the students to work it out for themselves. According to his longtime colleague James Chadwick, discoverer of the neutron, he wasn’t even particularly clever at experimentation. He was simply tenacious and open-minded. For brilliance he substituted shrewdness and a kind of daring. His mind, in the words of one biographer, was "always operating out towards the frontiers, as far as he could see, and that was a great deal further than most other men." Confronted with an intractable problem, he was prepared to work at it harder and longer than most people and to be more receptive to unorthodox explanations. His greatest breakthrough came because he was prepared to spend immensely tedious hours sitting at a screen counting alpha particle scintillations, as they were known—the sort of work that would normally have been farmed out. He was one of the first to see—possibly the very first—that the power inherent in the atom could, if harnessed, make bombs powerful enough to "make this old world vanish in smoke."

尽管他取得那么多成就,但他不是个特别聪明的人,实际上在数学方面还很差劲。在讲课过程中,他往往把自己的等式搞乱,不得不中途停下来,让学生自己去算出结果。据与他长期共事的同事、中子的发现者詹姆斯·查德威克说,他对实验也不是特别擅长。他只是有一股子韧劲儿,思想比较开放。他以精明和一点胆量代替了聪明。用一位传记作家的话来说,在他看来,他的脑子“总是不着边际,比大多数人走得远得多”。要是遇上一个难题,他愿意付出比大多数人更大的努力,花出更多的时间,而且更容易接受非正统的解释。由于他愿意坐在荧光屏前,花上许多极其乏味的时间来统计所谓α粒子的闪烁次数——这种工作通常分配给别人去做——所以他才有了最伟大的突破。他是最先的人之一——很可能就是最先的人——发现原子里所固有的能量一旦得到利用可以制造炸弹,其威力之大足以“使这个旧世界在烟雾中消失”。