(单词翻译:单击)

In 1969, in an attempt to bring some order to the growing inadequacies of classification, an ecologist from Cornell University named R. H. Whittaker unveiled in the journalScience a proposal to divide life into five principal branches—kingdoms, as they are known—called Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, and Monera. Protista, was a modification of an earlier term, Protoctista, which had been suggested a century earlier by a Scottish biologist named John Hogg, and was meant to describe any organisms that were neither plant nor animal.

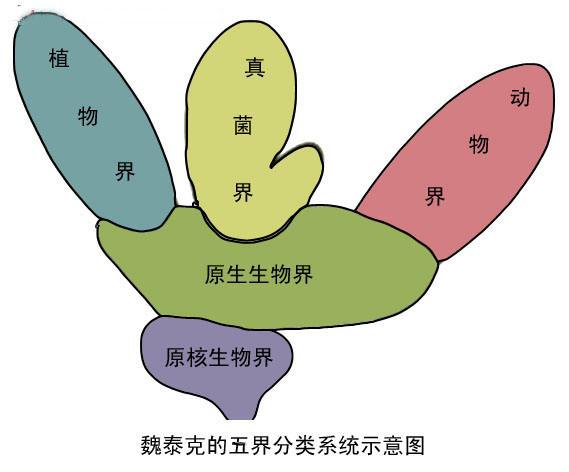

1969年,为了整理一下越来越显得不足的分类法,康奈尔大学一位名叫R.H.魏泰克的生态学家在《科学》杂志上提出了一个建议,把生物分成五个主要部分——即所谓的“界”——动物界、植物界、真菌界、原生生物界、和原核生物界。原生生物原先是由苏格兰生物学家约翰·霍格提出来的,用来描述非植物,非动物的任何生物。

Though Whittaker's new scheme was a great improvement, Protista remained ill defined. Some taxonomists reserved it for large unicellular organisms—the eukaryotes—but others treated it as the kind of odd sock drawer of biology, putting into it anything that didn't fit anywhere else. It included (depending on which text you consulted) slime molds, amoebas, and even seaweed, among much else. By one calculation it contained as many as 200,000 different species of organism all told. That's a lot of odd socks.

虽然魏泰克的新方案是个很大的改进,但原生生物界的含义仍没有明确界定。有的分类学家把这个名称保留起来指大的单细胞微生物——真核细胞,但有的把它当做生物池放单只袜子的抽屉,把任何归在哪里都不合适的东西塞到里面,其中包括(取决于你查阅的是什么资料)黏性杆菌、变形虫,甚至海藻。据有人计算,它总共包括了多达20万种不同的生物。那可是一大堆单只袜子呀。

Ironically, just as Whittaker's five-kingdom classification was beginning to find its way into textbooks, a retiring academic at the University of Illinois was groping his way toward a discovery that would challenge everything. His name was Carl Woese, and since the mid-1960s—or about as early as it was possible to do so—he had been quietly studying genetic sequences in bacteria.

具有讽刺意味的是,正当魏泰克的五界分类法开始被写进教材的时候,伊利诺伊大学一位脚踏实地的学者即将完成一个发现。这项发现将向一切提出挑战。他的名字叫卡尔·沃斯,自20世纪60年代以来——或者说,早在有可能办这种事的时候——他一直在默默地研究细菌的遗传连贯性。