(单词翻译:单击)

In 1980, the econometrician David Hendry (now Sir David) investigated a key economic question: what causes inflation? Hendry looked to the data for insight. He speculated that a particular variable, X, was largely responsible. He assembled data on variable X, performed a few deft mathematical tweaks and compared his transformed X with the path of consumer prices in the UK. Graphing the result showed an astonishingly close fit.

1980年,计量经济学家戴维亨德里(David Hendry,如今的戴维爵士)研究了一个重要的经济学问题:是什么引起了通胀?亨德里为此查阅了数据。他推测,特定变量X负有主要责任。他收集了变量X的数据,在数学计算上进行了一些巧妙的变换,再把变换后的X与英国消费者价格的趋势进行对比。绘制的结果表现出惊人的贴合。

The only snag: X was cumulative rainfall. Since consumer prices and cumulative rainfall both rise over time, Hendry had an excellent platform for finding his spurious correlation. Statistical sleight of hand did the rest.

唯一的问题是:X是累积降水量。由于消费者价格和累积降水量均随着时间的推移而增加,亨德里得到了一个寻找虚假关联度的完美平台,然后利用了统计学花招。

Hendry wanted to demonstrate just how easy it was to produce plausible nonsense by misusing the tools of statistics. “It is meaningless to talk about ‘confirming’ theories when spurious results are so easily obtained,” he wrote.

亨德里只是想证明,错误地使用统计学工具是多么容易得出看似合理的荒谬结论。“在站不住脚的结果可以如此轻易得到的情况下,讨论‘验证’理论毫无意义,”他写道。

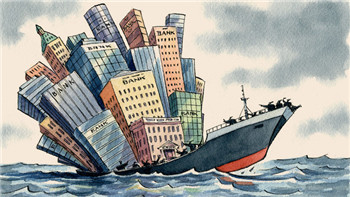

All this is by way of preamble, because a hot topic in economics at the moment is the role of finance in the health of the economy. For many years, economists have tended to believe that a larger financial sector tends to be good news for economic growth, with statistical evidence to back this up.

这一切都是序言,因为当今经济学的一个热门话题是金融对于经济健康的作用。多年来,经济学家已经倾向于认为,较大的金融部门对于经济增长往往是好消息,这一点得到了统计学证据的支撑。

It won’t surprise anyone to hear that this belief is now viewed with some scepticism, and the statistical studies now back up the scepticism too. Several recent research papers have found that finance can be bad for economic growth.

没有人会感到意外的是,如今一些人用怀疑的眼光审视这个观点,而统计学研究竟然也支持这种怀疑态度。最近一些研究论文发现,金融可能会不利于经济增长。

Given this statistical volte-face, Hendry’s conjuring trick comes to mind. Are our statistical studies simply serving as decoration for our existing prejudices?

鉴于此次统计学的倒戈,亨德里的统计学花招映入脑海。统计学研究只是在装饰我们现有的偏见吗?

A recent note by William Cline of the Peterson Institute for International Economics worries that new anti-finance research rests on a statistical illusion. Rich countries tend to grow more slowly than poorer ones. But rich countries also have larger banking sectors. A naive analysis, then, would show that large banking sectors are correlated with slower growth. But, points out Cline, the same statistical methods show that doctors are bad for growth and that telephones are bad for growth and even that research and development technicians are bad for growth. In reality, all that is being shown is that being rich already is bad for further growth.

彼得森国际经济研究所(Peterson Institute for International Economics)的威廉克莱恩(William Cline)在最近一份研究报告中表达了担忧——新的反金融研究是建立在统计学假象基础上的。与较贫穷的国家相比,富裕国家往往增长更慢。但是,富裕国家同时也拥有规模更大的银行部门。于是,幼稚的分析将据此推断,大型银行部门与较慢的增长之间存在相关性。但是,克莱恩指出,同样的统计学方法也可以显示医生不利于增长、电话不利于增长、甚至研发专家也不利于增长。而事实上,唯一能够得出的结论是,已经达到富有不利于进一步增长。

Cline makes a good point but a narrow one. It’s not particularly helpful to analyse banking like salt in cooking or water on your vegetable patch, and conclude that “some is good, too much is bad”. Unlike salt and water, banking services are complex and diverse. There’s a difference between a mortgage, a payday loan, life insurance, a credit derivative, a venture capital investment and an equity tracker fund. They’re all financial services, though.

克莱恩的观点没错,但有狭隘之嫌。像考虑煮菜时放多少盐或者菜园里浇多少水一样研究银行业,然后得出“适量很好,过量不好”的结论,并不是特别有用。不同于放盐或浇水,银行业的服务复杂而多样。抵押贷款、发薪日贷款(一种合法的高利贷——译者注)、人寿保险、信用衍生品、风险资本投资以及股票指数基金是不同的。但它们都是金融服务。

More persuasive analyses of the relationship between finance and growth are asking not just whether finance can grow too big to be helpful but what kind of finance, and why.

对于金融和增长之间关系,更具说服力的分析并不仅是设问金融会否发展到太大而无用,而是问何种金融不利于增长,原因是什么。

In two working papers for DNB, the Dutch central bank, Christiane Kneer explores the idea that the trouble with banking is that it sucks talent away from the rest of the economy. Kneer looked at the process of banking deregulation state by state in the US and found that banks hired skilled individuals away from manufacturing, where labour productivity fell. If Kneer is right, too much finance is bad for growth because the banks are gobbling up too many of the smartest workers.

在为荷兰央行(DNB)所作的两份工作报告中,克里斯蒂亚娜克内尔(Christiane Kneer)探究了这样一个观点,那就是银行业的麻烦在于它从经济的其他领域挖走了太多人才。克内尔一个州一个州地研究了美国银行业放松监管的经过,发现银行业从制造业挖走了高技能人才,而制造业的劳动生产率下降。如果克内尔的观点是正确的,过多金融不利于增长的原因是,金融业抢走了太多的顶级人才。

Another possibility, explored by economists Stephen Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi, is that large banking sectors aren’t doing their classic textbook job of funding the most productive investments. Instead, they like to lend money to organisations that already have collateral. Mortgages make attractive loans for this reason. Loans to a business that already owns an office block or an oil refinery are also tempting. But lending to a business with more intangible assets, such as an R&D department or a set of strong consumer relationships, is less attractive. Perhaps it is no surprise when Cecchetti and Kharroubi find that larger banking sectors are correlated with slower growth in R&D-intensive parts of the economy. But it is not encouraging.

经济学家史蒂芬切凯蒂(Stephen Cecchetti)和艾尼塞哈鲁比(Enisse Kharroubi)探索了另一个可能,即大型银行部门并未履行其在经典教科书中的职责——为最具成效的投资提供资金。相反,它们喜欢向已经有抵押物的组织放贷。正是由于这个原因,抵押贷款成了具有吸引力的贷款。向已经拥有写字楼或炼油厂的企业放贷也颇具吸引力。但是向拥有较多无形资产(比如研发部门或一系列强大的客户关系)的企业放贷,则没那么具有吸引力。切凯蒂和哈鲁比发现,在研发密集型的经济领域,较大的银行部门与较慢的增长之间存在相关性,这或许并不令人意外,但不是好事。

. . .

. . .

Such research reminds us that we shouldn’t simply bash “banking” or “finance” in some generic way, blaming the banks for anything from the weather to the struggles of bees. We need to look at the details of what the financial services industry is doing, and whether financial regulations are protecting society or making things worse.

这类研究提醒了我们,不应该只是笼统地敲打“银行业”或“金融”,把从天气到蜜蜂陷入困境的一切问题都归咎于银行。我们需要看一看金融服务业活动的细节,以及金融法规是在保护社会还是让事情变得更糟。

The truth is that we desperately need a strong banking sector. This entire research literature on finance and growth was originally kicked off by development economists who had observed that poor countries struggled to develop if they didn’t have decent banks. Thorsten Beck, an economist at Cass Business School, first started studying the effects of finance when he worked at the World Bank. “I didn’t care about the UK or the Netherlands. I cared about Kenya, Chile and Brazil.”

真相是我们绝对需要一个强大的银行部门。有关金融与增长的整套研究文献,最初是由发展经济学家奠基的,他们注意到穷国如果没有像样的银行便难以发展。卡斯商学院(Cass Business School)的经济学家托斯滕贝克(Thorsten Beck)最初是在世界银行(World Bank)工作期间开始研究金融的影响。“我那时不关心英国和荷兰。我关心的是肯尼亚、智利和巴西。”

Without a strong and sizeable banking sector to lend money to businesses, it is very hard for a poor country to grow. It may well be that we have more finance sloshing around the economy than we can use. That is a big problem — but it is also a first-world problem.

没有强大而成规模的银行部门向企业放贷,贫穷国家很难发展。我们很可能面对在整个经济体四处涌流的金融活动,超出我们可以利用的规模。这是个大问题——但也是第一世界的问题。