(单词翻译:单击)

双语小说

“It’s not so bad now,” he said, meaning since he had become the day manager at the gas station. But I’d seen the way he winced and rubbed his wrists on damp days. The way sweat erupted on his forehead as he reached for his bottle of antacids after meals. “Besides, I didn’t bring us here for me, did I?”

I reached across the table and put my hand on his. My student hand, clean and soft, on his laborer’s hand, grubby and calloused. I thought of all the trucks, train sets, and bikes he’d bought me in Kabul. Now America. One last gift for Amir.

Just one month after we arrived in the U.S., Baba found a job off Washington Boulevard as an assistant at a gas station owned by an Afghan acquaintance--he’d started looking for work the same week we arrived. Six days a week, Baba pulled twelve-hour shifts pumping gas, running the register, changing oil, and washing windshields. I’d bring him lunch sometimes and find him looking for a pack of cigarettes on the shelves, a customer waiting on the other side of the oil-stained counter, Baba’s face drawn and pale under the bright fluorescent lights. The electronic bell over the door would ding-dong when I walked in, and Baba would look over his shoulder, wave, and smile, his eyes watering from fatigue.

The same day he was hired, Baba and I went to our eligibility officer in San Jose, Mrs. Dobbins. She was an overweight black woman with twinkling eyes and a dimpled smile. She’d told me once that she sang in church, and I believed her--she had a voice that made me think of warm milk and honey. Baba dropped the stack of food stamps on her desk. “Thank you but I don’t want,” Baba said. “I work always. In Afghanistan I work, in America I work. Thank you very much, Mrs. Dobbins, but I don’t like it free money.”

Mrs. Dobbins blinked. Picked up the food stamps, looked from me to Baba like we were pulling a prank, or “slipping her a trick” as Hassan used to say. “Fifteen years I been doin’ this job and nobody’s ever done this,” she said. And that was how Baba ended those humiliating food stamp moments at the cash register and alleviated one of his greatest fears: that an Afghan would see him buying food with charity money. Baba walked out of the welfare office like a man cured of a tumor. THAT SUMMER OF 1983, I graduated from high school at the age of twenty, by far the oldest senior tossing his mortarboard on the football field that day. I remember losing Baba in the swarm of families, flashing cameras, and blue gowns. I found him near the twenty-yard line, hands shoved in his pockets, camera dangling on his chest. He disappeared and reappeared behind the people moving between us: squealing blue-clad girls hugging, crying, boys high-fiving their fathers, each other. Baba’s beard was graying, his hair thinning at the temples, and hadn’t he been taller in Kabul? He was wearing his brown suit--his only suit, the same one he wore to Afghan weddings and funerals--and the red tie I had bought for his fiftieth birthday that year. Then he saw me and waved. Smiled. He motioned for me to wear my mortarboard, and took a picture of me with the school’s clock tower in the background. I smiled for him--in a way, this was his day more than mine. He walked to me, curled his arm around my neck, and gave my brow a single kiss. “I am moftakhir, Amir,” he said. Proud. His eyes gleamed when he said that and I liked being on the receiving end of that look.

He took me to an Afghan kabob house in Hayward that night and ordered far too much food. He told the owner that his son was going to college in the fall. I had debated him briefly about that just before graduation, and told him I wanted to get a job. Help out, save some money, maybe go to college the following year. But he had shot me one of his smoldering Baba looks, and the words had vaporized on my tongue.

After dinner, Baba took me to a bar across the street from the restaurant. The place was dim, and the acrid smell of beer I’d always disliked permeated the walls. Men in baseball caps and tank tops played pool, clouds of cigarette smoke hovering over the green tables, swirling in the fluorescent light. We drew looks, Baba in his brown suit and me in pleated slacks and sports jacket. We took a seat at the bar, next to an old man, his leathery face sickly in the blue glow of the Michelob sign overhead. Baba lit a cigarette and ordered us beers. “Tonight I am too much happy,” he announced to no one and everyone. “Tonight I drinking with my son. And one, please, for my friend,” he said, patting the old man on the back. The old fellow tipped his hat and smiled. He had no upper teeth.

Baba finished his beer in three gulps and ordered another. He had three before I forced myself to drink a quarter of mine. By then he had bought the old man a scotch and treated a foursome of pool players to a pitcher of Budweiser. Men shook his hand and clapped him on the back. They drank to him. Someone lit his cigarette. Baba loosened his tie and gave the old man a handful of quarters. He pointed to the jukebox. “Tell him to play his favorite songs,” he said to me. The old man nodded and gave Baba a salute. Soon, country music was blaring, and, just like that, Baba had started a party.

At one point, Baba stood, raised his beer, spilling it on the sawdust floor, and yelled, “Fuck the Russia!” The bar’s laughter, then its full-throated echo followed. Baba bought another round of pitchers for everyone.

When we left, everyone was sad to see him go. Kabul, Peshawar, Hayward. Same old Baba, I thought, smiling.

I drove us home in Baba’s old, ochre yellow Buick Century. Baba dozed off on the way, snoring like a jackhammer. I smelled tobacco on him and alcohol, sweet and pungent. But he sat up when I stopped the car and said in a hoarse voice, “Keep driving to the end of the block.”

“Why, Baba?”

“现在还好啦。”他说,他的意思是自升任加油站日班经理之后。但在天气潮湿的日子,我总能见到他忍痛揉着手腕。也见过他在饭后,头冒冷汗去拿止痛药瓶子的模样。“再说,我又不是为了自己才让我们两个来到这里的,你知道吗?”

我把手伸过桌子,握住他的手。我的是学生哥儿的手,干净柔软;他的是劳动者的手,肮脏且长满老茧。我想起在喀布尔时,他给我买的所有那些卡车、火车玩具,还有那些自行车。如今,美国是爸爸送给阿米尔的最后一件礼物。

我们到美国仅一个月之后,爸爸在华盛顿大道找到工作,在一个阿富汗熟人开的加油站当助理——他从我们到美国那天就开始找工作了。每周六天,每天轮班十二小时,爸爸给汽车加油、收银、换油、擦洗挡风玻璃。有好几次,我带午饭给他吃,发现他正在货架上找香烟,油污斑斑的柜台那端,有个顾客在等着,在明亮的荧光映衬下,爸爸的脸扭曲而苍白。每次我走进去,门上的电铃会“叮咚叮咚”响,爸爸会抬起头,招招手,露出微笑,他的双眼因为疲累而流泪。

被聘请那天,爸爸和我到圣荷塞[1]SanJose,美国加利福尼亚州城市。[1]去找我们的移民资格审核官杜宾斯太太。她是个很胖的黑人妇女,眼睛明亮,笑起来露出两个酒窝。有一回她跟我说她在教堂唱歌,我相信——她的声音让我想起热牛奶和蜂蜜。爸爸将一叠食物券放在她的柜台上。“谢谢你,可是我不想要。”爸爸说,“我一直有工作。在阿富汗,我有工作;在美国,我有工作。非常感谢,杜宾斯太太,可是我不喜欢接受施舍。”

杜宾斯太太眨眨眼,把食物券捡起来,看看我,又看看爸爸,好像我们在开她玩笑,或者像哈桑经常说的“耍她一下”。“我干这行十五年了,从来没人这么做过。”她说。就是这样,爸爸结束了在收银台用食物券支付的屈辱日子,也消除了他最担心的事情之一:被阿富汗人看到他用救济金买食物。爸爸走出福利办公室时,好像大病初愈。1983年那个夏天,我20岁,高中毕业。那天在足球场上掷帽子的人中,要数我最老了。我记得球场上满是蓝色袍子,学生的家人、闪光的镜头,把爸爸淹没了。我在二十码线附近找到他,双手插袋,相机在胸前晃荡。我们之间隔着一群人,一会儿把他挡住,一会儿他又出现。穿蓝色衣服的女生尖叫着,相互拥抱,哭泣;男生和他们的父亲拍掌庆贺。爸爸的胡子变灰了,鬓边的头发也减少了,还有,难道他在喀布尔更高?他穿着那身棕色西装——他只有这么一套,穿着它参加阿富汗人的婚礼和葬礼——系着那年他五十岁生日时我送的红色领带。接着他看到我,挥挥手,微笑。他示意我戴上方帽子,以学校的钟楼为背景,替我拍了张照片。我朝他微笑着——在某种意义上,那日子与其说是我的,毋宁说是他的。他朝我走来,伸手揽住我的脖子,亲吻了我的额头。“我很骄傲,阿米尔。”他说。他说话的时候眼睛闪亮,那样的眼光望着的是我,让我很高兴。

那晚,他带我到海沃德[1]Hayward,美国加利福尼亚州城市,近弗里蒙特。[1]的阿富汗餐厅,点了太多的食物。他跟店主说,他的儿子秋天就要上大学了。毕业之前,我就上大学的事情跟他稍稍争论过,告诉他我想工作,补贴家用,存些钱,也许次年才上大学。但他恨铁不成钢地盯了我一眼,我只好闭嘴。

晚饭后,爸爸带我去饭店对面的酒吧。那地方光线阴暗,墙壁上散发着我素来不喜欢的啤酒酸味。男人们头戴棒球帽,身穿无袖上衣,玩着撞球,绿色的桌子上烟雾升腾,袅袅绕着荧光灯。爸爸穿着棕色西装,我穿着打褶长裤和运动外套,显得格外引人注目。我们在吧台找到位子,坐在一个老人身边。老人头上有个麦克罗啤酒的商标,发出蓝光,将他那张沧桑的脸照得病恹恹的。爸爸点了根香烟,给我们要了啤酒。“今晚我太高兴了!”他自顾自地向每个人宣布,“今晚我带我的儿子来喝酒。来,请给我的朋友来一杯。”他的手拍在那个老人背上。老头抬抬帽子,露出微笑,他没有上排的牙齿。

爸爸三口就喝完了他的啤酒,又要了一杯。我强迫自己,还没喝完四分之一,他已经干掉三杯了。他请那个老头一杯苏格兰烈酒,还请那四个打撞球的家伙一大罐百威。人们同他握手,用力拍他的后背。他们向他敬酒,有人给他点烟。爸爸松了松领带,给那个老人一把二毛五分的硬币,指指电唱机。“告诉他,来几首他最拿手的。”他对我说。老人点点头,向爸爸敬礼。不久就响起乡村音乐,就像这样,爸爸开始宴会了。

酒到酣处,爸爸站起来,举起酒杯,将它摔在遍地锯屑的地板,高声喊叫。“操他妈的俄国佬!”酒吧里爆发出一阵笑声,大家高声附和,爸爸又给每个人买啤酒。

我们离开的时候,大家都舍不得他走。喀布尔,白沙瓦,海沃德。爸爸还是爸爸,我想,微笑着。

我开着爸爸那辆土黄色的旧别克世纪轿车,驶回我们家。爸爸在路上睡着了,鼾声如气钻。我在他身上闻到烟草的味道,还有酒精味,甜蜜而辛辣。但我在停车的时候,他醒过来,嘶哑的嗓音说:“继续开,到街道那边去。”

“干吗,爸爸?”

作品周边

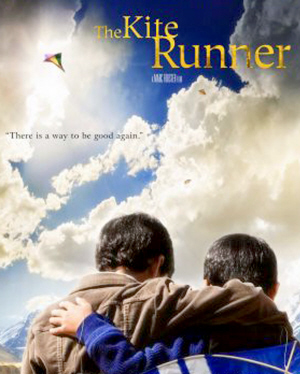

内容简介

12岁的阿富汗富家少爷阿米尔与仆人哈桑情同手足。然而,在一场风筝比赛后,发生了一件悲惨不堪的事,阿米尔为自己的懦弱感到自责和痛苦,逼走了哈桑,不久,自己也跟随父亲逃往美国。

成年后的阿米尔始终无法原谅自己当年对哈桑的背叛。为了赎罪,阿米尔再度踏上暌违二十多年的故乡,希望能为不幸的好友尽最后一点心力,却发现一个惊天谎言,儿时的噩梦再度重演,阿米尔该如何抉择?

故事如此残忍而又美丽,作者以温暖细腻的笔法勾勒人性的本质与救赎,读来令人荡气回肠。

作者简介

卡勒德·胡赛尼(Khaled Hosseini),1965年生于阿富汗喀布尔市,后随父亲迁往美国。胡赛尼毕业于加州大学圣地亚哥医学系,现居加州。“立志拂去蒙在阿富汗普通民众面孔的尘灰,将背后灵魂的悸动展示给世人。”著有小说《追风筝的人》(The Kite Runner,2003)、《灿烂千阳》(A Thousand Splendid Suns,2007)、《群山回唱》(And the Mountains Echoed,2013)。作品全球销量超过4000万册。2006年,因其作品巨大的国际影响力,胡赛尼获得联合国人道主义奖,并受邀担任联合国难民署亲善大使。

精选评论

热门评论

对友谊最大的误解,就是认为它是万能的(来自豆瓣网友:谢长留)

我时常幻想自己是来自未来的,这样,有一天我面对未来某一时刻的突然变化,就会更从容,面对陈年往事也会更慷慨。但,我更适合平庸,如寻常人一样琐碎繁杂的生活,对时间的细枝末节斤斤计较。

既然无法预知未来,那么人更多的开始依赖回忆,甚至靠那些零星琐碎的回忆支撑往后的日子,有些回忆很美好,有些回忆很心酸,有些回忆让人长大,有些回忆让人显得很无知,有些回忆慢慢泛黄,有些回忆仿佛就在昨天。有些故事也总是从儿时的回忆展开。

我对阿富汗以及周边连年征战的国家和他们的历史毫无兴趣,对我而言,那里的人民是可怜的,那里的政府是可悲的,所以当《追风筝的人》这个故事一点一点展现在我面前的时候,我并没准备好接受一个平静的,也曾春暖花开,羊肉串香飘整条街的画面,更没想到那里的孩子也可以无忧无虑的追逐风筝。

所以当身为少爷的阿米尔和他的仆人哈桑情同手足的画面一出现,所有读者不禁感叹,少年时的友谊是那么充满力量,干净而持久的。他们总是并肩而行,每当阿米尔被人欺负的时候,哈桑总是义无反顾的站出来保护,很多人说这是哈桑天生的奴性,这种观点我不赞同,我看见他们之间分明有一道友谊的光芒在闪耀。

当阿米尔问哈桑为什么确定自己一定会知道被切断绳线的风筝的掉落地的时候,哈桑肯定的对阿米尔说,我就是知道,然后反问,我什么时候骗过你。阿米尔轻声说,我怎么知道有没有骗过我。哈桑发誓,为了你,我宁可啃烂泥。阿米尔进一步确定,你真的会为我啃烂泥?哈桑坚定的说,我肯定,然后又说,但是你又怎么能忍心让我啃烂泥。所以读者心中所向往的也就是我们每个人心中那个潮湿的童年印象,总是和自己最亲密的伙伴,席地而坐,互相盟誓,发誓为对方,甘愿上刀山下火海。就如同哈桑洋溢着笑脸对阿米尔说的那样:为你,千千万万遍。

然而事实上却是这样的:他是主人,他是仆人;他是普什图,他是哈扎拉;他是逊尼派,他是什叶派,从他们出生的那一刻起,他们的命运就被这些他们所不能理解的标签所分隔开来,尽管他们是亲密无间的朋友,尽管他们事实上拥有同一位父亲。无论是平凡的阿米尔和哈桑,还是高高在上的查希尔国王或者卡尔扎伊,都不得不接受社会为他们预定的座位——阿米尔不再是阿米尔,哈桑也不再是哈桑,他们必须戴上社会分给他们的面具。

哈桑总是说“为你,千千万万遍”,而生性懦弱的阿米尔却选择沉默冷酷的逃避,这样的悲剧性结果并不单单是个性差异所造成的,在这些年少无知的孩子的潜意识里早已被灌输了相应于自身社会地位的“应该”与“不应该”,一个哈扎拉仆人理应为主人尽忠,而高贵的普什图少爷不值得为一个卑贱的哈扎拉仆人冒任何风险。

“阿米尔和哈桑,喀布尔的统治者”,这样的誓言只能是石榴树下的童话,“王子与贫儿”不可能成为兄弟,因为他们命中注定不平等。包括二十年后,阿米尔重返阿富汗的自我救赎行为,也只不过是在获知自己与哈桑的同父异母兄弟关系之后对身世的无奈认可,也就是说,他仍然没有证明自己已经找到了“重新成为好人的路”。

我们少年的时候,总是意气风发,三五结伴,促膝长谈。那是在我们其乐融融的环境中构建的虚拟场景,属于物理学讲究的理想状态,然而在残酷的现实面前,在微弱的友谊遇到挑战的时刻,只要有一方露出破绽,友谊的桥梁必然坍塌。

于是当阿米尔在看到哈桑被大一些的孩子欺负甚至猥亵的时候,他选择沉默和逃避;与此同时,哈桑却为了阿米尔的风筝坚定不动摇的和对手较量,对手残忍的揭示阿米尔和哈桑之间的主仆关系,哈桑大声反驳说两个人是朋友。躲在角落里不敢出现的阿米尔听到这句话不但没有一点激励也没有丝毫感动,他心底里的怯懦终于将他的灵魂吞噬,于是悲剧发生。

这就是我们对友谊最大的误解,认为它是万能的。

即使是存在这样的问题,《追风筝的人》也还是一本出色的小说。主和仆、贵族和贱民、朋友和兄弟,历史和现实,种种转变都被刻画得生动而细腻。放在历史的宏大背景下,更洞见人生和人性的复杂。

友谊和爱。

是在困难之中由弱变强的柔韧派还是在权衡利弊之中土崩瓦解的懦弱派。

谁敢真的站出来举起右手发誓,我从来没有辜负过任何一段纯粹的友谊,谁敢真的抬头挺胸说自己对朋友忠心不二。

我们总是太自信,对友谊误解,对自己的爱误解,对不可能的事信以为真。