(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

And one day, when the wound burned violently, Siddhartha ferried across the river, driven by a yearning, got off the boat and was willing to go to the city and to look for his son. The river flowed softly and quietly, it was the dry season, but its voice sounded strange: it laughed! It laughed clearly. The river laughed, it laughed brightly and clearly at the old ferryman. Siddhartha stopped, he bent over the water, in order to hear even better, and he saw his face reflected in the quietly moving waters, and in this reflected face there was something, which reminded him, something he had forgotten, and as he thought about it, he found it: this face resembled another face, which he used to know and love and also fear. It resembled his father's face, the Brahman. And he remembered how he, a long time ago, as a young man, had forced his father to let him go to the penitents, how he had bed his farewell to him, how he had gone and had never come back. Had his father not also suffered the same pain for him, whichhe now suffered for his son? Had his father not long since died, alone, without having seen his son again? Did he not have to expect the same fate for himself? Was it not a comedy, a strange and stupid matter, this repetition, this running around in a fateful circle?

The river laughed. Yes, so it was, everything came back, which had not been suffered and solved up to its end, the same pain was suffered over and over again. But Siddhartha want back into the boat and ferried back to the hut, thinking of his father, thinking of his son, laughed at by the river, at odds with himself, tending towards despair, and not less tending towards laughing along at himself and the entire world.

Alas, the wound was not blossoming yet, his heart was still fighting his fate, cheerfulness and victory were not yet shining from his suffering. Nevertheless, he felt hope, and once he had returned to the hut, he felt an undefeatable desire to open up to Vasudeva, to show him everything, the master of listening, to say everything.

Vasudeva was sitting in the hut and weaving a basket. He no longer used the ferry-boat, his eyes were starting to get weak, and not just his eyes; his arms and hands as well. Unchanged and flourishing was only the joy and the cheerful benevolence of his face.

Siddhartha sat down next to the old man, slowly he started talking. What they had never talked about, he now told him of, of his walk to the city, at that time, of the burning wound, of his envy at the sight of happy fathers, of his knowledge of the foolishness of such wishes, of his futile fight against them. He reported everything, he was able to say everything, even the most embarrassing parts, everything could be said, everything shown, everything he could tell. He presented his wound, also told how he fled today, how he ferried across the water, a childish run-away, willing to walk to the city, how the river had laughed.

While he spoke, spoke for a long time, while Vasudeva was listening with a quiet face, Vasudeva's listening gave Siddhartha a stronger sensation than ever before, he sensed how his pain, his fears flowed over to him, how his secret hope flowed over, came back at him from his counterpart. To show his wound to this listener was the same as bathing it in the river, until it had cooled and become one with the river. While he was still speaking, still admitting and confessing, Siddhartha felt more and more that this was no longer Vasudeva, no longer a human being, who was listening to him, that this motionless listener was absorbing his confession into himself like a tree the rain, that this motionless man was the river itself, that he was God himself, that he was the eternal itself. And while Siddhartha stopped thinking of himself and his wound, this realisation of Vasudeva's changed character took possession of him, and the more he felt it and entered into it, the less wondrous it became, the more he realised that everything was in order and natural, that Vasudeva had already been like this for a long time, almost forever, that only he had not quite recognised it, yes, that he himself had almost reached the same state. He felt, that he was now seeing old Vasudeva as the people see the gods, and that this could not last; in his heart, he started bidding his farewell to Vasudeva. Thorough all this, he talked incessantly.

When he had finished talking, Vasudeva turned his friendly eyes, which had grown slightly weak, at him, said nothing, let his silent love and cheerfulness, understanding and knowledge, shine at him. He took Siddhartha's hand, led him to the seat by the bank, sat down with him, smiled at the river.

一天,这伤口痛得厉害,席特哈尔塔受不了思念之苦就渡过河去,下船之后打算去城里找儿子。河水在轻柔地流淌,当时正是旱季,但河水声有点儿特别:它在笑!它在清清楚楚地笑。河水在笑,在清脆响亮地嘲笑这个老船夫。席特哈尔塔停下了,他弯腰俯到水面上,想听得更清楚些。他看见自己的脸映在静静流淌的水面上,这张脸使他忆起了什么,忆起了某些已经淡记的东西。他忖思,终于发现:这张脸跟中一张他熟悉、热爱但又畏惧的脸很相似。它很像他父亲的脸,那个婆罗门的脸。他回忆起多年以前,他还是个年轻人,他怎样迫使父亲同意他出门苦修,怎样同父亲告别,离家后又怎样再也没回去。他父亲岂不是也为他受了同样的苦,就像他现在为儿子所受的苦一样?他父亲不是早就死去了吗,孤孤单单地再也没能见到儿子?他自己又何尝不会遭遇到同样的命运?这种重复,这种绕着一个倒霉的圈子旋转的循环,难道不是一出喜剧,一件奇特而荒唐的事?

河水在笑。是的,事情正是如此,只要还没有熬到头,还没有得到解脱,一切都会这样重复,再三经受同样的痛苦。席特哈尔塔重又登上小船,返回了茅屋。他思念父亲,思念儿子,被河水嘲笑,与自我争执,倾向于绝望,也同样倾向于大声嘲笑自己以及整个世界。

啊,伤口还没有开花,他的心还在同命运抗争,他的痛苦还没有放射出喜悦和胜利的光芒。可是他感觉到了希望,他回到茅屋后感觉到了一种不可抑制的愿望,要向瓦苏代瓦敞开心扉,向他坦述一切,向这位倾听的大师诉说一切。

瓦苏代瓦正坐在茅屋里编一个篮子。他已经不再撑船了,因为他的视力已开始衰退,不仅他的眼睛,他的胳臂和手也不行了。只有他脸上的欢乐和开朗的善意没有改变,依然神采奕奕。

席特哈尔塔坐在老人身边,开始慢慢地讲述。他现在讲的是过去从来没讲过的事,讲他当年进城之行,讲那灼痛的伤口,讲他见到别的幸福父亲时的嫉妒,讲他知道这种愿望的愚蠢,讲他进行的徒劳无益的斗争。他什么都讲,什么都肯讲,哪怕是最最难这情的事,他什么都说,什么都可以暴露,什么都可以讲出来。他展示自己的伤口,也讲了今天想逃走的事,讲他如何渡过河去,他这个幼稚可笑的逃跑者,打算去城里,以及河水如何嘲笑他。

他讲啊讲,讲了很久,瓦苏代瓦脸色平静地倾听着。席特哈尔塔觉得瓦苏代瓦此刻的倾听比他以往感到的更强有力,他感觉到了自己的痛苦、自己的忧虑如何传过去,他的隐密的希望如何传过去,再从老人那边传回来。向这位倾听者展示自己的伤口,就像他们在河里洗澡一样,一直洗到浑身都凉快了,与河水融为一体。席特哈尔塔一直在讲述,滔滔不绝地坦白和忏悔,他越来越感到听他讲的不再是瓦苏代瓦,不再是一个人,这个一动不动的倾听者吸取了他的忏悔,就像是一棵树吸足了雨水,这个一动不动的人就是河水,就是神,就是永恒。当席特哈尔塔不再想自己以及自己的伤口时,这种认为瓦苏代瓦已改变了本质的认识支配了他,他越是感受到这点,越是深入探究,就越是不奇怪,越是认识到,一切都很正常和自然,瓦苏代瓦早就是这样,几乎一直是这样,只不过他自己没有完全认识到而已。是的,他自己也几乎没有什么不同。他觉得,他现在这样看待老瓦苏代瓦,就像凡人看待神,这是不会长久的;他已开始开始在心里向瓦苏代瓦告别。而与此同时,他仍然在一直不停地讲述着。

他讲完之后,瓦苏代瓦便用他那亲切的、有些昏花的目光望着他,不说话,只是默默地向他传送着爱与快乐,传送着理解与体谅。他拉起席特哈尔塔的手,带着他来到河边的老地方,和他一起坐下来,笑着面向河水。

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

作者简介:

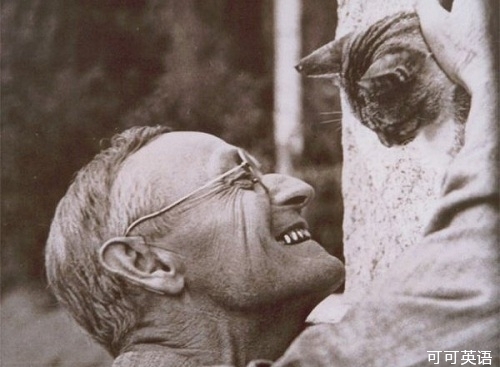

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

豆瓣热门书评:席特哈尔塔与乔达摩悉达多

来自: 宠物跳蚤

不算评论,只是想谈一个简单的问题。

因为这种情况在我读杨玉功翻译的《悉达多》的时候也发生过。最初总是在“悉达多就是佛教的创始人”这个语境中,直到悉达多去拜访佛陀,也就是乔达摩的时候,我开始困惑不已。

在这个方面,不能不说译者杨玉功应该负主要责任。他的那篇颇有些自鸣得意的序我印象很深刻,一种少年得意之情充斥其中:二十多岁就把全书译完,现在再看觉得还是没有什么不妥的地方;对旧翻译书名音译(即《席特哈尔塔》)有所不满,更指出了一处错误“潜入水中”,他说应翻译为“在水面行走”。恰恰是他得意的书名《悉达多》,误导了很多人,认为这是佛教创始人的一篇西方作家所做的传记,甚至连一些我国出的西方文学史(特别是一部五卷本的德国文学史)谈到此书时也作是评。

实际上如此吗?

当然不!下面从几个方面来说明。

为了区分,《悉达多》一书的主人公悉达多,我们用旧翻译,即音译,席特哈尔塔。

从现实的层面讲,乔达摩悉达多,也就是佛教的创始人应当为其全名,而悉达多仅仅是名而已。书中写的婆罗门贵族青年席特哈尔塔仅仅和佛祖重名(作者是否有意另作讨论),就像张伟,刘伟,王伟一样,怎么能就此认为是佛教创始人呢?而且佛祖乔达摩悉达多出身为印度四大种姓的另一个:刹帝利。

从书中的内容讲,席特哈尔塔曾经拜访了已经尊为佛祖的乔达摩悉达多,作者分明把两人区别开来,怎么可以再将两者混淆?佛祖的传道首先是在鹿野苑,而席特哈尔塔也就是本书的主人公拜访并师从之后,认为乔达摩悉达多是位伟人,但其学说或者体悟并不能满足自己的心灵——这一点很重要,下面马上提到,希望大家注意。

再从思想的深度来讲,《悉达多》(《席特哈尔塔》)之所以会风靡全世界,假如它只是一本佛祖的西方传记,恐怕根本达不到那种动人心魄的效果,事实上,从作者自身思想发展来看,他虽然对印度的哲学很有兴趣,并非真的信服,反而越到后来越是靠近中国的古代哲学,比如老子。

纵观黑塞一生的创作历程,会发现作者不断地在探讨的并非是某一种宗教或者学说让书中的主人公乃至书后的黑塞本人信服,而是这些东西或启发,或阻碍主人公作为一个“人”对自身心灵在现实世界中的探寻。黑塞本人在现实生活中也是这么做的,他没有埋头在书房里冥思苦想,而是走了很多地方,在最接近大自然的地方独自居住,经历了三次婚姻,遭遇无数的误解,他不但写小说,写诗歌,而且还画画。从《盖特路德》《罗斯哈尔德》到《席特哈尔塔》到《纳尔齐斯和歌尔德蒙》,哪一个主人公不是在现实生活中不断地追寻?不断经历生活?如果将《席特哈尔塔》理解为佛祖的传记,真是把黑塞的视野极大的狭隘化了。

我们再重温一下席特哈尔塔所经历过的吧:沙门,静修,物质之富,欲望之淫,亲情之痛,自然之歌。这些是佛教所能概括的吗,难道他最后皈依的是佛教吗?不,他最后皈依的是自然,连皈依佛教静修多年的旧友侨文达也崇敬地望着他,难以理解席特哈尔塔如何达到这样的境界。

“他深深地鞠躬,一躬到地,向端坐不动的席特哈尔塔敬礼,席特哈尔塔的笑容让他忆起了自己一生中曾经爱过的一切,忆起了自己一生中认为宝贵和神圣的一切。”

我们不禁想到歌尔德蒙弥留中追问纳尔齐斯:“可你将来想怎么死呢,纳尔齐斯,你没有母亲?人没有母亲就不能爱,没有母亲也不能死啊!”

这并非无欲无求的佛心,而是不可言传的大道。

附:黑塞与道的关系需另论,此文目的在于辨明乔达摩悉达多和席特哈尔塔绝非一人,并且此书绝非佛祖传记。