(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

But Siddhartha knew what his friend was thinking. He thought, the boy would have thrown away or broken the oar in order to get even and in order to keep them from following him. And in fact, there was no oar left in the boat. Vasudeva pointed to the bottom of the boat and looked at his friend with a smile, as if he wanted to say: "Don't you see what your son is trying to tell you? Don't you see that he doesn't want to be followed?" But he did not say this in words. He started making a new oar. But Siddhartha bid his farewell, to look for the run-away. Vasudeva did not stop him.

When Siddhartha had already been walking through the forest for a long time, the thought occurred to him that his search was useless. Either, so he thought, the boy was far ahead and had already reached the city, or, if he should still be on his way, he would conceal himself from him, the pursuer. As he continued thinking, he also found that he, on his part, was not worried for his son, that he knew deep inside that he had neither perished nor was in any danger in the forest. Nevertheless, he ran without stopping, no longer to save him, just to satisfy his desire, just to perhaps see him one more time. And he ran up to just outside of the city.

When, near the city, he reached a wide road, he stopped, by the entrance of the beautiful pleasure-garden, which used to belong to Kamala, where he had seen her for the first time in her sedan-chair. The past rose up in his soul, again he saw himself standing there, young, a bearded, naked Samana, the hair full of dust. For a long time, Siddhartha stood there and looked through the open gate into the garden, seeing monks in yellow robes walking among the beautiful trees.

For a long time, he stood there, pondering, seeing images, listening to the story of his life. For a long time, he stood there, looked at the monks, saw young Siddhartha in their place, saw young Kamala walking among the high trees. Clearly, he saw himself being served food and drink by Kamala, receiving his first kiss from her, looking proudly and disdainfully back on his Brahmanism, beginning proudly and full of desire his worldly life. He saw Kamaswami, saw the servants, the orgies, the gamblers with the dice, the musicians, saw Kamala's song-bird in the cage, lived through all this once again, breathed Sansara, was once again old and tired, felt once again disgust, felt once again the wish to annihilate himself, was once again healed by the holy Om.

After having been standing by the gate of the garden for a long time, Siddhartha realised that his desire was foolish, which had made him go up to this place, that he could not help his son, that he was not allowed to cling him. Deeply, he felt the love for the run-away in his heart, like a wound, and he felt at the same time that this wound had not been given to him in order to turn the knife in it, that it had to become a blossom and had to shine.

That this wound did not blossom yet, did not shine yet, at this hour, made him sad. Instead of the desired goal, which had drawn him here following the runaway son, there was now emptiness. Sadly, he sat down, felt something dying in his heart, experienced emptiness, saw no joy any more, no goal. He sat lost in thought and waited. This he had learned by the river, this one thing: waiting, having patience, listening attentively. And he sat and listened, in the dust of the road, listened to his heart, beating tiredly and sadly, waited for a voice. Many an hour he crouched, listening, saw no images any more, fell into emptiness, let himself fall, without seeing a path. And when he felt the wound burning, he silently spoke the Om, filled himself with Om. The monks in the garden saw him, and since he crouched for many hours, and dust was gathering on his gray hair, one of them came to him and placed two bananas in front of him. The old man did not see him.

From this petrified state, he was awoken by a hand touching his shoulder. Instantly, he recognised this touch, this tender, bashful touch, and regained his senses. He rose and greeted Vasudeva, who had followed him. And when he looked into Vasudeva's friendly face, into the small wrinkles, which were as if they were filled with nothing but his smile, into the happy eyes, then he smiled too. Now he saw the bananas lying in front of him, picked them up, gave one to the ferryman, ate the other one himself. After this, he silently went back into the forest with Vasudeva, returned home to the ferry. Neither one talked about what had happened today, neither one mentioned the boy's name, neither one spoke about him running away, neither one spoke about the wound. In the hut, Siddhartha lay down on his bed, and when after a while Vasudeva came to him, to offer him a bowl of coconut-milk, he already found him asleep.

可是,席特哈尔塔知道他的朋友在想什么。他在想,孩子会把船桨扔掉或者弄断,为了报复,也为了防止他们追赶。果然,小船里没有了船桨。瓦苏代瓦指指船底,微笑地望着朋友,似乎要说:“你没看出儿子要跟你说什么吗?你没看出他不愿被人追踪吗?”不过,他并没把这话说出来。他动手制作了一支新船桨。席特哈尔塔同他道别,去找逃跑的孩子。瓦苏代瓦没有阻拦他。

席特哈尔塔在森林里找了很久,才意识到他的搜寻毫无用处。他寻思,孩子说不定早就走出了森林,已经回到城里了,要是他还在路上,那么他看见追踪者就会躲起来。他继续想,发现自己并不为儿子担心,他内心深处知道,儿子既不会丧命,也不会在森里遇到危险。不过,尽管如此,他还是不停地赶路,不再是为了救孩子,而只是出于想再见孩子一面的渴望。他就这样一直赶到了城市。

他走近城市,踏上宽阔的大街,来到那个原来属于卡玛拉的漂亮花园大门口站住了。他就是在这儿子第一次看见了坐在轿子里的卡玛拉。当时的情景又浮现在脑海中,他依稀看见自己站在那儿,年纪轻轻,一个胡子拉碴、赤身露体的沙门,满头尘土。席特哈尔塔伫立了很久,从敞开的大门往花园里望,看见身穿黄僧衣的和尚们在茂密的树下走动。

他伫立了很久,沉思着,似乎看见了一幅幅画面,听见了自己的生活故事。他伫立了很久,望着那些和尚,仿佛看到的不是他们,而是年轻的席特哈尔塔,是年轻的卡玛拉在大树下走。他清晰地看到自己如何受到卡玛拉款待,如何得到她的第一个吻,如何自豪而又轻蔑地回顾他的婆罗门生涯,自豪而又渴望地开始他的世俗生活。他看到了卡马斯瓦密,看到了仆人们,那些盛宴,那些赌徒,那些乐师,看到了那只被卡玛拉关在笼子里的小鸟,再一次体验了这一切,充满了轮回之念,于是再一次衰老和疲倦,再一次感到恶心,再一次感受到那种寻求解脱的愿望,再一次靠着圣洁的“唵”才恢复了健康。

席特哈尔塔在花园门口伫立了很久,才意识到驱使自己来到此处的希望是愚蠢的,他并不能帮助儿子,他不该拽住儿子不放。他内心深深感到对逃亡者的爱,这就像一个创伤,可是他同时也感到,这创伤并不是让他哀叹感慨的,它势必会开花结果,大放光彩。

然而,此记得这创伤还没有开花结果,还没有大放光彩,这使得他很伤心。促使他来到这儿追寻失踪的儿子的目标既已消失,取而代之的便是一片空虚。他悲伤地坐下,感到心中有什么正在死去,感到空虚,看不到欢乐,看不到目标。他坐在那里出神,等待着。这是他在河边学会的本领:等耐,有耐心,倾听。他坐在大街上的尘土中倾听,倾听自己的心如何疲乏而悲哀地跳动,期待着一个声音。他坐在那儿倾听了几个钟头,再也看不见以往的情景,陷入空虚之中,听任自己沉沦,看不到一条路。他感到作品灼痛时就默诵“唵”,以“唵”来充实自己。花园里的和尚看见了他,因为他已坐了好多个钟头,花白头发落满了灰尘。于是,有一个和尚走过来,在他面前放下了两个芭蕉。老人没看到他。

一只手碰了碰他的肩,把他从这种麻木中唤醒了。他马上就认出了这触碰,这温柔、扭怩的触碰,苏醒过来。他站起身,向来找他的瓦苏代瓦问好。他望着瓦苏代瓦那和蔼可亲的脸,望着那溢满了笑容的细密的皱纹,望着那双开朗的眼睛,也笑了。这时,他看见了面前的芭蕉,递一个给船夫,自己吃了另一个。随后,他默默地跟着瓦苏代瓦返回了森林,返回了渡口。谁也不说今天发生的事,谁也不提孩子的名字,谁也不谈他的逃走,谁也不点到那伤口。回到茅屋里,席特哈尔塔躺到自己的床上。过了一会儿,瓦苏代瓦来到他身边,端给他一碗椰子 汁,却发现他已经睡着了。

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

作者简介:

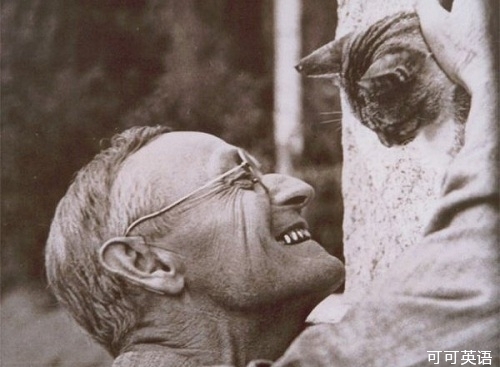

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

豆瓣热门书评:席特哈尔塔与乔达摩悉达多

来自: 宠物跳蚤

不算评论,只是想谈一个简单的问题。

因为这种情况在我读杨玉功翻译的《悉达多》的时候也发生过。最初总是在“悉达多就是佛教的创始人”这个语境中,直到悉达多去拜访佛陀,也就是乔达摩的时候,我开始困惑不已。

在这个方面,不能不说译者杨玉功应该负主要责任。他的那篇颇有些自鸣得意的序我印象很深刻,一种少年得意之情充斥其中:二十多岁就把全书译完,现在再看觉得还是没有什么不妥的地方;对旧翻译书名音译(即《席特哈尔塔》)有所不满,更指出了一处错误“潜入水中”,他说应翻译为“在水面行走”。恰恰是他得意的书名《悉达多》,误导了很多人,认为这是佛教创始人的一篇西方作家所做的传记,甚至连一些我国出的西方文学史(特别是一部五卷本的德国文学史)谈到此书时也作是评。

实际上如此吗?

当然不!下面从几个方面来说明。

为了区分,《悉达多》一书的主人公悉达多,我们用旧翻译,即音译,席特哈尔塔。

从现实的层面讲,乔达摩悉达多,也就是佛教的创始人应当为其全名,而悉达多仅仅是名而已。书中写的婆罗门贵族青年席特哈尔塔仅仅和佛祖重名(作者是否有意另作讨论),就像张伟,刘伟,王伟一样,怎么能就此认为是佛教创始人呢?而且佛祖乔达摩悉达多出身为印度四大种姓的另一个:刹帝利。

从书中的内容讲,席特哈尔塔曾经拜访了已经尊为佛祖的乔达摩悉达多,作者分明把两人区别开来,怎么可以再将两者混淆?佛祖的传道首先是在鹿野苑,而席特哈尔塔也就是本书的主人公拜访并师从之后,认为乔达摩悉达多是位伟人,但其学说或者体悟并不能满足自己的心灵——这一点很重要,下面马上提到,希望大家注意。

再从思想的深度来讲,《悉达多》(《席特哈尔塔》)之所以会风靡全世界,假如它只是一本佛祖的西方传记,恐怕根本达不到那种动人心魄的效果,事实上,从作者自身思想发展来看,他虽然对印度的哲学很有兴趣,并非真的信服,反而越到后来越是靠近中国的古代哲学,比如老子。

纵观黑塞一生的创作历程,会发现作者不断地在探讨的并非是某一种宗教或者学说让书中的主人公乃至书后的黑塞本人信服,而是这些东西或启发,或阻碍主人公作为一个“人”对自身心灵在现实世界中的探寻。黑塞本人在现实生活中也是这么做的,他没有埋头在书房里冥思苦想,而是走了很多地方,在最接近大自然的地方独自居住,经历了三次婚姻,遭遇无数的误解,他不但写小说,写诗歌,而且还画画。从《盖特路德》《罗斯哈尔德》到《席特哈尔塔》到《纳尔齐斯和歌尔德蒙》,哪一个主人公不是在现实生活中不断地追寻?不断经历生活?如果将《席特哈尔塔》理解为佛祖的传记,真是把黑塞的视野极大的狭隘化了。

我们再重温一下席特哈尔塔所经历过的吧:沙门,静修,物质之富,欲望之淫,亲情之痛,自然之歌。这些是佛教所能概括的吗,难道他最后皈依的是佛教吗?不,他最后皈依的是自然,连皈依佛教静修多年的旧友侨文达也崇敬地望着他,难以理解席特哈尔塔如何达到这样的境界。

“他深深地鞠躬,一躬到地,向端坐不动的席特哈尔塔敬礼,席特哈尔塔的笑容让他忆起了自己一生中曾经爱过的一切,忆起了自己一生中认为宝贵和神圣的一切。”

我们不禁想到歌尔德蒙弥留中追问纳尔齐斯:“可你将来想怎么死呢,纳尔齐斯,你没有母亲?人没有母亲就不能爱,没有母亲也不能死啊!”

这并非无欲无求的佛心,而是不可言传的大道。

附:黑塞与道的关系需另论,此文目的在于辨明乔达摩悉达多和席特哈尔塔绝非一人,并且此书绝非佛祖传记。