(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

KAMALA

Siddhartha learned something new on every step of his path, for the world was transformed, and his heart was enchanted. He saw the sun rising over the mountains with their forests and setting over the distant beach with its palm-trees. At night, he saw the stars in the sky in their fixed positions and the crescent of the moon floating like a boat in the blue. He saw trees, stars, animals, clouds, rainbows, rocks, herbs, flowers, stream and river, the glistening dew in the bushes in the morning, distant hight mountains which were blue and pale, birds sang and bees, wind silverishly blew through the rice-field. All of this, a thousand-fold and colourful, had always been there, always the sun and the moon had shone, always rivers had roared and bees had buzzed, but in former times all of this had been nothing more to Siddhartha than a fleeting, deceptive veil before his eyes, looked upon in distrust, destined to be penetrated and destroyed by thought, since it was not the essential existence, since this essencelay beyond, on the other side of, the visible. But now, his liberated eyes stayed on this side, he saw and became aware of the visible, sought to be at home in this world, did not search for the true essence, did not aim at a world beyond. Beautiful was this world, looking at it thus, without searching, thus simply, thus childlike. Beautiful were the moon and the stars, beautiful was the stream and the banks, the forest and the rocks, the goat and the gold-beetle, the flower and the butterfly. Beautiful and lovely it was, thus to walk through the world, thus childlike, thus awoken, thus open to what is near, thus without distrust. Differently the sun burnt the head, differently the shade of the forest cooled him down, differently the stream and the cistern, the pumpkin and the banana tasted. Short were the days, short the nights, every hour sped swiftly away like a sail on the sea, and under the sail was a ship full of treasures, full of joy. Siddhartha saw a group of apes moving through the high canopy of theforest, high in the branches, and heard their savage, greedy song. Siddhartha saw a male sheep following a female one and mating with her. In a lake of reeds, he saw the pike hungrily hunting for its dinner; propelling themselves away from it, in fear, wiggling and sparkling, the young fish jumped in droves out of the water; the scent of strength and passion came forcefully out of the hasty eddies of the water, which the pike stirred up, impetuously hunting.

All of this had always existed, and he had not seen it; he had not been with it. Now he was with it, he was part of it. Light and shadow ran through his eyes, stars and moon ran through his heart.

On the way, Siddhartha also remembered everything he had experienced in the Garden Jetavana, the teaching he had heard there, the divine Buddha, the farewell from Govinda, the conversation with the exalted one. Again he remembered his own words, he had spoken to the exalted one, every word, and with astonishment he became aware of the fact that there he had said things which he had not really known yet at this time. What he had said to Gotama: his, the Buddha's, treasure and secret was not the teachings, but the unexpressable and not teachable, which he had experienced in the hour of his enlightenment--it was nothing but this very thing which he had now gone to experience, what he now began to experience. Now, he had to experience his self. It is true that he had already known for a long time that his self was Atman, in its essence bearing the same eternal characteristics as Brahman. But never, he had really found this self, because he had wanted to capture it in the net of thought. With the body definitely not being the self, and not the spectacle of the senses, so it also was not the thought, not the rational mind, not the learned wisdom, not the learned ability to draw conclusions and to develop previous thoughts in to new ones. No, this world of thought was also still on this side, and nothing could be achieved by killing the random self of the senses, if the random self of thoughts and learned knowledge was fattened on the other hand. Both, the thoughts as well as the senses, were pretty things, the ultimate meaning was hidden behind both of them, both had to be listened to, both had to be played with, both neither had to be scorned nor overestimated, from both the secret voices of the innermost truth had to be attentively perceived. He wanted to strive for nothing, except for what the voice commanded him to strive for, dwell on nothing, except where the voice would advise him to do so. Why had Gotama, at that time, in the hour of all hours, sat down under the bo-tree, where the enlightenment hit him? He hadheard a voice, a voice in his own heart, which had commanded him to seek rest under this tree, and he had neither preferred self-castigation, offerings, ablutions, nor prayer, neither food nor drink, neither sleep nor dream, he had obeyed the voice. To obey like this, not to an external command, only to the voice, to be ready like this, this was good, this was necessary, nothing else was necessary.

In the night when he slept in the straw hut of a ferryman by the river, Siddhartha had a dream: Govinda was standing in front of him, dressed in the yellow robe of an ascetic. Sad was how Govinda looked like, sadly he asked: Why have you forsaken me? At this, he embraced Govinda, wrapped his arms around him, and as he was pulling him close to his chest and kissed him, it was not Govinda any more, but a woman, and a full breast popped out of the woman's dress, at which Siddhartha lay and drank, sweetly and strongly tasted the milk from this breast. It tasted of woman and man, of sun and forest, of animal and flower, of every fruit, of every joyful desire. It intoxicated him and rendered him unconscious.--When Siddhartha woke up, the pale river shimmered through the door of the hut, and in the forest, a dark call of an owl resounded deeply and pleasantly.

When the day began, Siddhartha asked his host, the ferryman, to get him across the river. The ferryman got him across the river on his bamboo-raft, the wide water shimmered reddishly in the light of the morning.

"This is a beautiful river," he said to his companion.

卡玛拉

席特哈尔塔在自己的路上每走一步都学到新东西,因为世界发生了变化,他的心完全被迷住了。他看见太阳从密林覆盖的山峰上升起,又在远方的棕榈海滩处落下。他看见夜间天空中星斗罗列,弯月如一叶小舟在蓝天中飘游。他看见树木、星斗、动物、云团、彩虹、岩石、杂草、鲜花、小溪与河流,清晨的灌木丛中有露珠在闪烁,远方的高山淡蓝和灰白,鸟儿啼鸣,蜜蜂嗡嗡,清风悠悠地吹过稻田。这一切都千变万化,五彩缤纷,而且历来如此,日月总是照耀,河水总是流淌,蜜蜂总是哼唱,然而在以前,这一切对于席特哈尔塔来说都只是蒙在他眼前的一层虚无缥缈的轻纱,带着怀疑细看,注定要被思想浸透和消灭,因为它们并非本质,因为本质是在超然于可见之处的另一边。如今,他的得到解放的眼睛则停留在这一边,看见和认出了可见的东西,在这个世界上寻找家园,不是寻求本 质,不是对准那一边。世界是美好的,只要你这样不带探究、这样单纯、这样天真地去看它。月亮和星星是美丽的,小溪和河岸是美丽的,此外还有森林和山岩,山羊和金龟子孙,鲜花和蝴蝶。这样漫游世界,这样天真,这样清醒,这样坦诚交往,这样没有戒心,的确是美好和可爱的。有时让太阳直晒头顶,有时在树荫下乘凉,有时啜饮小溪和池塘的水,有时品尝南瓜和香蕉。白天显得短促,夜晚也显得短促,每一个钟头都过得飞快,就好像大海上的一张帆,而在帆下面是一艘满载珍宝和欢乐的船。席特哈尔塔看见一群猴子在高高的树梢上游荡,在高高的枝杈间跳跃,并且听见一种粗野、渴求的啼声。席特哈尔塔看见一只公羊追逐一只母羊并与之交媾。在一片芦苇荡里,他看见梭鱼由于饥饿而追逐捕食,小鱼在他面前成群地跃出水面,惊恐万分,扑击翻腾,熠熠闪光。凶猛的捕食者搅起阵阵水涡,散发出力量和激情。

所有这一切都是历来如此,可是以前他却没见到,因为他没有到过这里。现在他来了,他理应属于这里。光和影掠过他的眼,星星和月亮映入他的心。

席特哈尔塔在路上又想起了他在耶塔瓦纳林苑经历的一切,想起他在那儿听过的教诲,想起活佛,想起他与戈文达的分别,想起他与活佛的谈话。他回忆自己当时对活佛讲过的话,回忆每一句话,惊讶地注意到自己居然讲了当时他还根本不知道的事。他对戈塔马所说的一切——他的事,活佛的事,珍贵和秘密的并不是学问,而是他在茅塞顿开时体验到的无可言传和难以讲授的东西——这也正是他现在准备经历的东西,他现在开始经历的东西。现在他必须体验自我。他早就清楚他的自我就是阿特曼,像婆罗门一样具有永恒的性质。可是,他从来没有真正找到过这个自我,因为原来他是想用思想之网去捕获它。如果说身体不是自我,本义的游戏不是自我,那么,思想也不是自我。要想得出结论并且从已经思考过的东西推出新想法,理性不行,学到的智慧不行,学到的技巧也不行。不,这个思想世界也还是尘世的,如果扼杀这个偶然的感觉的自我,却去喂肥那个偶然的思想和学问的自我,那是不会达到什么目标的。思想和感觉,这两者都是可爱的事物,这两者后面都潜藏着最后的意识,两者都值得倾听,都值得打交道,既不可轻视也不可高估,应当从这两者来了解内心深处的稳秘声音。他只想追求这个声音命令他追求的东西,他只想在这个声音建议他停留的地方停留。当初,在他豁然开朗的时候,戈塔马为什么是坐在菩提树下?当时他听见了一个声音,自己心中的一个声音,吩咐他在这棵树下歇息,他没有先进行苦修、祭祀、沐浴或祈祷,没吃也没喝,没睡觉也没做梦,而是听从了这个声音。他就这么服从了,不是服从外来的命令,而是服从这个声音,心甘情愿地服从。这是对的,是必要的,是必不可少的。

夜里,席特哈尔塔睡在河边一个船夫的茅草屋里,做了一个梦:戈文达站在他面前,穿着一件黄僧衣。戈文达的样子很伤心,他伤心地问:“你为什么离开我?”于是他拥抱戈文达,伸出两臂搂住他,把他紧贴在自己胸前,亲吻他。谁知这时不再是戈文达了,变成了一个女人,从这个女人的衣裳里露出一个丰满的乳房,席特哈乐塔凑到乳房上吸吮,乳汁又甜又香。那是女人和男人的味道,太阳和森林的味道,动物和鲜花的味道,各种果实的味道,各种乐趣的味道。它使人陶醉,醉得不省人事。——当席特哈尔塔醒来时,灰白的河水透过茅屋的小门闪着微光,树林里响起猫头鹰的一声神秘啼叫,深沉而又响亮。

天亮了,席特哈尔塔请求那个款待他的主人,也就是那个船夫,摆渡他过河去。船夫用竹筏送他过了河,宽阔的水面在晨曦中闪着微红的光。

“这是一条美丽的河。”他对船夫说。

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

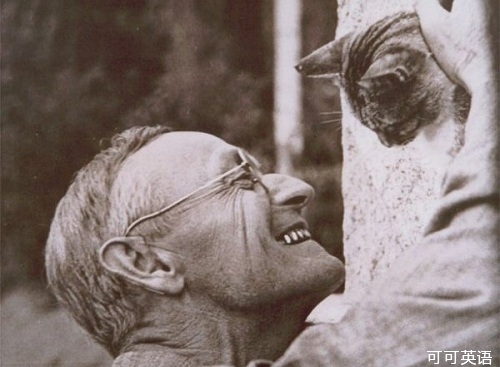

作者简介:

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

主要生平及创作

出生于德国西南部的小城卡尔夫的一个牧师家庭。自幼在浓重的宗教气氛中长大,1891年,他通过“邦试”,考入毛尔布隆神学校。由于不堪忍受经院教育的摧残,半年后逃离学校。这期间他游历许多城市,从事过多种职业。

在比较广泛地接受东西方文化熏陶之后,1904年,黑塞发表了长篇小说《彼得·卡门青特》,一举成名,从此成为专业作家。这一年他与玛丽结婚,移居巴登湖畔,埋头写作,1906年发表了长篇小说《在轮下》。这一时期的创作以浪漫主义诗歌、田园诗风格的抒情小说和流浪汉小说为主,作品洋溢着对童年和乡土的思念之情,充满对广大自然和人类的爱,同时也表现了青年人的精神苦闷与追求。

第一次世界大战后,黑塞的创作发生了明显的变化,他醉心于尼采哲学,求助于印度佛教和中国的老庄哲学,并对荣格的精神分析产生了深厚的兴趣。他试图从宗教、哲学和心理学方面探索人类精神解放的途径。这时期的长篇小说有《克努尔普》(1916)、《德米安》(1919)、《席特哈尔塔》(1922)、《荒原狼》(1927)和《纳尔齐斯与歌尔德蒙》(1930)等。这些书深受西方读者的喜爱,得到极高的评价,其中《荒原狼》曾轰动欧美,被托马斯·曼誉为德国的《尤利西斯》。

30年代后,法西斯在德国猖獗,黑塞对社会前途陷入深深的怀疑与绝望之中,但他仍不倦地从东西方宗教与哲学中寻求理想世界,《东方之行》(1932)、《玻璃球游戏》(1943)正是这一时期追求与探索的结晶。

黑塞被雨果·巴尔称为德国浪漫派最后一位骑士,这说明他在艺术上深受浪漫主义诗歌的影响。他热爱大自然,厌倦都市文明,作品多采用象征手法,文笔优美细腻;由于受精神分析影响,他的作品着重在精神领域里进行挖掘探索,无畏而诚实地剖析内心,因此他的小说具有心理的深度。1946年,"由于他的富于灵感的作品具有遒劲的气势和洞察力,也为崇高的人道主义理想和高尚风格提供一个范例",黑塞获诺贝尔文学奖。