(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

By his side lived Govinda, his shadow, walked the same paths, undertook the same efforts. They rarely spoke to one another, than the service and the exercises required. Occasionally the two of them went through the villages, to beg for food for themselves and their teachers.

"How do you think, Govinda," Siddhartha spoke one day while begging this way, "how do you think did we progress? Did we reach any goals?"

Govinda answered: "We have learned, and we'll continue learning. You'll be a great Samana, Siddhartha. Quickly, you've learned every exercise, often the old Samanas have admired you. One day, you'll be a holy man, oh Siddhartha."

Quoth Siddhartha: "I can't help but feel that it is not like this, my friend. What I've learned, being among the Samanas, up to this day, this, oh Govinda, I could have learned more quickly and by simpler means. In every tavern of that part of a town where the whorehouses are, my friend, among carters and gamblers I could have learned it."

Quoth Govinda: "Siddhartha is putting me on. How could you have learned meditation, holding your breath, insensitivity against hunger and pain there among these wretched people?"

And Siddhartha said quietly, as if he was talking to himself: "What is meditation? What is leaving one's body? What is fasting? What is holding one's breath? It is fleeing from the self, it is a short escape of the agony of being a self, it is a short numbing of the senses against the pain and the pointlessness of life. The same escape, the same short numbing is what the driver of an ox-cart finds in the inn, drinking a few bowls of rice-wine or fermented coconut-milk. Then he won't feel his self any more, then he won't feel the pains of life any more, then he finds a short numbing of the senses. When he falls asleep over his bowl of rice-wine, he'll find the same what Siddhartha and Govinda find when they escape their bodies through long exercises, staying in the non-self. This is how it is, oh Govinda."

Quoth Govinda: "You say so, oh friend, and yet you know that Siddhartha is no driver of an ox-cart and a Samana is no drunkard. It's true that a drinker numbs his senses, it's true that he briefly escapes and rests, but he'll return from the delusion, finds everything to be unchanged, has not become wiser, has gathered no enlightenment,--has not risen several steps."

And Siddhartha spoke with a smile: "I do not know, I've never been a drunkard. But that I, Siddhartha, find only a short numbing of the senses in my exercises and meditations and that I am just as far removed from wisdom, from salvation, as a child in the mother's womb, this I know, oh Govinda, this I know."

And once again, another time, when Siddhartha left the forest together with Govinda, to beg for some food in the village for their brothers and teachers, Siddhartha began to speak and said: "What now, oh Govinda, might we be on the right path? Might we get closer to enlightenment? Might we get closer to salvation? Or do we perhaps live in a circle-- we, who have thought we were escaping the cycle?"

Quoth Govinda: "We have learned a lot, Siddhartha, there is still much to learn. We are not going around in circles, we are moving up, the circle is a spiral, we have already ascended many a level."

Siddhartha answered: "How old, would you think, is our oldest Samana, our venerable teacher?"

Quoth Govinda: "Our oldest one might be about sixty years of age."

And Siddhartha: "He has lived for sixty years and has not reached the nirvana. He'll turn seventy and eighty, and you and me, we will grow just as old and will do our exercises, and will fast, and will meditate. But we will not reach the nirvana, he won't and we won't. Oh Govinda, I believe out of all the Samanas out there, perhaps not a single one, not a single one, will reach the nirvana. We find comfort, we find numbness, we learn feats, to deceive others. But the most important thing, the path of paths, we will not find."

"If you only," spoke Govinda, "wouldn't speak such terrible words, Siddhartha! How could it be that among so many learned men, among so many Brahmans, among so many austere and venerable Samanas, among so many who are searching, so many who are eagerly trying, so many holy men, no one will find the path of paths?"

But Siddhartha said in a voice which contained just as much sadness as mockery, with a quiet, a slightly sad, a slightly mocking voice: "Soon, Govinda, your friend will leave the path of the Samanas, he has walked along your side for so long. I'm suffering of thirst, oh Govinda, and on this long path of a Samana, my thirst has remained as strong as ever. I always thirsted for knowledge, I have always been full of questions. I have asked the Brahmans, year after year, and I have asked the holy Vedas, year after year, and I have asked the devote Samanas, year after year. Perhaps, oh Govinda, it had been just as well, had been just as smart and just as profitable, if I had asked the hornbill-bird or the chimpanzee. It took me a long time and am not finished learning this yet, oh Govinda: that there is nothing to be learned! There is indeed no such thing, so I believe, as what we refer to as `learning'. There is, oh my friend, just one knowledge, this is everywhere, this is Atman, this is within me and within you and within every creature. And so I'm starting to believe that this knowledge has no worser enemy than the desire to know it, than learning."

At this, Govinda stopped on the path, rose his hands, and spoke: "If you, Siddhartha, only would not bother your friend with this kind of talk! Truly, you words stir up fear in my heart. And just consider: what would become of the sanctity of prayer, what of the venerability of the Brahmans' caste, what of the holiness of the Samanas, if it was as you say, if there was no learning?! What, oh Siddhartha, what would then become of all of this what is holy, what is precious, what is venerable on earth?!"

戈文达在他身边生活,是他的影子,跟他走同样的路,受同样的磨难。他们互相很少讲话,只讲工作和修行所需的话。有时,他们两个人一起穿村过街,去为自己和老师化缘。

“你怎么想,戈文达?”席特哈尔塔在一次化缘途中问道,“你怎么想,咱们是继续前进吗?咱们达到目标了吗?”

戈文达回答:“咱们已经学会了,而且还要继续学下去。你会成为一个伟大的沙门,席特哈尔塔。每一种功夫你都学得很快,那些老沙门经常赞扬你。你总有一天会成为圣人,席特哈尔塔。”

席特哈尔塔说:“我可不这么看,朋友。迄今为止我向沙门到的东西,戈文达,其实可以更快更直截了当地学到。在妓院区的小酒馆里,朋友,在马车夫和赌徒中间,我其实也可以学到。”

戈文达说:“席特哈尔塔,你大概是在跟我开玩笑吧。在那些可怜虫那儿,你怎么能学会沉思潜修,怎么能学会屏息敛气,怎么能学会忍耐饥饿和痛苦呢?”

席特哈尔塔轻声回答,就好像在自言自语:“什么是沉思潜修?什么是脱离躯体?什么是斋戒?什么是屏息敛气?那都是逃离自我,是从自我的痛苦中短暂的挣脱,是对抗生活的痛苦和荒谬的短暂麻醉。这种逃脱,这种短暂麻醉,即使赶车人在小客栈里也可以找到,只要他喝上几杯米酒或发过酵的椰子汁就行。然后,他就不再感觉到自我,不再感觉到生活的痛苦,得到了短暂的麻醉。他喝了米酒后迷迷糊糊地入睡,找到的正是席特哈尔塔和戈文达找到的感觉,而咱们却得经过长期间的苦修后才能摆脱自己的躯壳,在非我之中停留。就是这么回事,戈文达。”

戈文达说:“你怎么这样说,朋友,你毕竟知道,席特哈尔塔不是赶牛人,而是一个沙门也不是酒鬼。酒鬼可以得到麻醉,得到短暂的逃避与休息,但是当他从幻觉中醒来时,就会发现一切仍是老样子,他并没有变得更聪明些,并没有积累什么知识,并没有登上更高的台阶。”

席特哈尔塔含笑说道:“我不知道这些,我从来没做过醉鬼。但是我,席特哈尔塔,在我的苦行与潜修中只是得到了短暂的麻醉,而距离智慧,距离获救却依然像我是母体中的胎儿时那么遥远,这点我知道,戈文达,这点我清楚。”

后来又有一次,席特哈尔塔与戈文达一起离开了森林,到村子里去为他们的弟兄和老师化缘。席特哈尔塔开口说道:“现在怎么样,戈文达,咱们大概走对了路了吧?咱们已经接近知识了吧?咱们已经接近获救了吧?抑或咱们只不过是在兜圈子——却自以为是逃脱了这种轮回?”

戈文达说:“咱们学到了很多东西,席特哈尔塔,可是也还有很多东西要再去学。咱们不是在原地兜圈子,而是往上走,这圆圈是个螺旋。咱们已经上了好几级台阶。”

席特哈尔塔说道:“你讲讲看,咱们那位老沙门,那个可敬的老师,大约多少岁了?”

戈文达说:“大概六十岁了吧。”

席特哈尔塔说:“他已经六十岁了,却还没有达到涅PAN。他可能会活到七十岁和八十岁,而你和我,咱们也同样会变老。咱们不停地苦练、斋戒和沉思潜修。可是,咱们都不会达到涅PAN,他不行,咱们也不行。哦,戈文达,我相信,在所有的沙门中大概没一个能达到涅PAN。咱们得到了安慰,得到了麻醉,学会了种种自我迷惑的技巧。但重要的是咱们没找到那条路中之路。”

戈文达说:“但愿你别说这么耸人听闻的话,席特哈尔塔!在这么多有学问的人当中,在这么多婆罗门当中,在这么多严肃和可敬的沙门当中,在这么多孜孜不倦、热心勤奋、高尚圣洁的人当中,怎么就没一个能找到那条路中之路呢?”

但是,席特哈尔塔却用一种既伤心又嘲讽的声音,用一种轻轻的、有些伤心又有些嘲讽的声音说道:“戈文达,你的朋友不久就要离开这条跟 你一起走了这么久的沙门之路了。我很干渴,戈文达,在这条漫长的沙门之路上,我的干渴丝毫也没能缓解。我一直在渴求知识,我一直充满了疑问。年复一年,我请教了婆罗门,年复一年,我请教了神圣的《吠陀》。啊,戈文达,或许我去向犀鸟或黑猩猩求教,也会同样有益,同样聪明,同样见效。啊,戈文达,我花费了很长的时间,现在仍没有结束,结果是弄明白了这点:并没有什么东西可学!因此我相信,实际上并没有那种咱们称之为‘学习’的东西。哦,朋友,只有一种知识是普通存在的,那就是阿特曼,它在我身上,也在你身上,它在每个人身上。于是,我开始相信:这种知识的死敌正是求知的欲望,是学习。”

戈文达在路上停下了,举起双手来说:“席特哈尔塔,你可千万别用这种话来吓你的朋友!真的,你的话在我心里引起了恐惧。你想想,假如真像你说的那样,没有了学习,那么,哪里还有祈祷的神圣,哪里还有婆罗门种姓的尊严,哪里还有沙门的神圣呢?!啊!席特哈尔塔,那么,世上一切神圣、宝贵和可敬的东西将会变成什么样子呢?!”

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

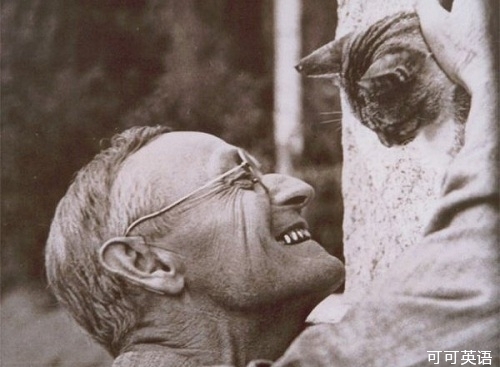

作者简介:

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

主要生平及创作

出生于德国西南部的小城卡尔夫的一个牧师家庭。自幼在浓重的宗教气氛中长大,1891年,他通过“邦试”,考入毛尔布隆神学校。由于不堪忍受经院教育的摧残,半年后逃离学校。这期间他游历许多城市,从事过多种职业。

在比较广泛地接受东西方文化熏陶之后,1904年,黑塞发表了长篇小说《彼得·卡门青特》,一举成名,从此成为专业作家。这一年他与玛丽结婚,移居巴登湖畔,埋头写作,1906年发表了长篇小说《在轮下》。这一时期的创作以浪漫主义诗歌、田园诗风格的抒情小说和流浪汉小说为主,作品洋溢着对童年和乡土的思念之情,充满对广大自然和人类的爱,同时也表现了青年人的精神苦闷与追求。

第一次世界大战后,黑塞的创作发生了明显的变化,他醉心于尼采哲学,求助于印度佛教和中国的老庄哲学,并对荣格的精神分析产生了深厚的兴趣。他试图从宗教、哲学和心理学方面探索人类精神解放的途径。这时期的长篇小说有《克努尔普》(1916)、《德米安》(1919)、《席特哈尔塔》(1922)、《荒原狼》(1927)和《纳尔齐斯与歌尔德蒙》(1930)等。这些书深受西方读者的喜爱,得到极高的评价,其中《荒原狼》曾轰动欧美,被托马斯·曼誉为德国的《尤利西斯》。

30年代后,法西斯在德国猖獗,黑塞对社会前途陷入深深的怀疑与绝望之中,但他仍不倦地从东西方宗教与哲学中寻求理想世界,《东方之行》(1932)、《玻璃球游戏》(1943)正是这一时期追求与探索的结晶。

黑塞被雨果·巴尔称为德国浪漫派最后一位骑士,这说明他在艺术上深受浪漫主义诗歌的影响。他热爱大自然,厌倦都市文明,作品多采用象征手法,文笔优美细腻;由于受精神分析影响,他的作品着重在精神领域里进行挖掘探索,无畏而诚实地剖析内心,因此他的小说具有心理的深度。1946年,"由于他的富于灵感的作品具有遒劲的气势和洞察力,也为崇高的人道主义理想和高尚风格提供一个范例",黑塞获诺贝尔文学奖。