(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

When in the next morning the time had come to start the day's journey, Govinda said, not without hesitation, these words: "Before I'll continue on my path, Siddhartha, permit me to ask one more question. Do you have a teaching? Do you have a faith, or a knowledge, you follow, which helps you to live and to do right?"

Quoth Siddhartha: "You know, my dear, that I already as a young man, in those days when we lived with the penitents in the forest, started to distrust teachers and teachings and to turn my back to them. I have stuck with this. Nevertheless, I have had many teachers since then. A beautiful courtesan has been my teacher for a long time, and a rich merchant was my teacher, and some gamblers with dice. Once, even a follower of Buddha, travelling on foot, has been my teacher; he sat with me when I had fallen asleep in the forest, on the pilgrimage. I've also learned from him, I'm also grateful to him, very grateful. But most of all, I have learned here from this river and from my predecessor, the ferryman Vasudeva. He was a very simple person, Vasudeva, he was no thinker, but he knew what is necessary just as well as Gotama, he was a perfect man, a saint."

Govinda said: "Still, oh Siddhartha, you love a bit to mock people, as it seems to me. I believe in you and know that you haven't followed a teacher. But haven't you found something by yourself, though you've found no teachings, you still found certain thoughts, certain insights, which are your own and which help you to live? If you would like to tell me some of these, you would delight my heart."

Quoth Siddhartha: "I've had thoughts, yes, and insight, again and again. Sometimes, for an hour or for an entire day, I have felt knowledge in me, as one would feel life in one's heart. There have been many thoughts, but it would be hard for me to convey them to you. Look, my dear Govinda, this is one of my thoughts, which I have found: wisdom cannot be passed on. Wisdom which a wise man tries to pass on to someone always sounds like foolishness."

"Are you kidding?" asked Govinda.

"I'm not kidding. I'm telling you what I've found. Knowledge can be conveyed, but not wisdom. It can be found, it can be lived, it is possible to be carried by it, miracles can be performed with it, but it cannot be expressed in words and taught. This was what I, even as a young man, sometimes suspected, what has driven me away from the teachers. I have found a thought, Govinda, which you'll again regard as a joke or foolishness, but which is my best thought. It says: The opposite of every truth is just as true! That's like this: any truth can only be expressed and put into words when it is one-sided. Everything is one-sided which can be thought with thoughts and said with words, it's all one-sided, all just one half, all lacks completeness, roundness, oneness. When the exalted Gotama spoke in his teachings of the world, he had to divide it into Sansara and Nirvana, into deception and truth, into suffering and salvation. It cannot be done differently, there is no other way for him who wants to teach. But theworld itself, what exists around us and inside of us, is never one-sided. A person or an act is never entirely Sansara or entirely Nirvana, a person is never entirely holy or entirely sinful. It does really seem like this, because we are subject to deception, as if time was something real. Time is not real, Govinda, I have experienced this often and often again. And if time is not real, then the gap which seems to be between the world and the eternity, between suffering and blissfulness, between evil and good, is also a deception.""How come?" asked Govinda timidly."Listen well, my dear, listen well! The sinner, which I am and which you are, is a sinner, but in times to come he will be Brahma again, he will reach the Nirvana, will be Buddha--and now see: these "times to come" are a deception, are only a parable! The sinner is not on his way to become a Buddha, he is not in the process of developing, though our capacity for thinking does not know how else to picture these things. No, within the sinner is now and today already the future Buddha, his future is already all there, you have to worship in him, in you, in everyone the Buddha which is coming into being, the possible, the hidden Buddha. The world, my friend Govinda, is not imperfect, or on a slow path towards perfection: no, it is perfect in every moment, all sin already carries the divine forgiveness in itself, all small children already have the old person in themselves, all infants already have death, all dying people the eternal life. It is not possible for any person to see how far another one has already progressed on his path; in the robber and dice-gambler, the Buddha is waiting; in the Brahman, the robber is waiting. In deep meditation, there is the possibility to put time out of existence, to see all life which was, is, and will be as if it was simultaneous, and there everything is good, everything is perfect, everything is Brahman. Therefore, I see whatever exists as good, death is to me like life, sin like holiness, wisdom like foolishness, everything has to be as it is, everything only requires my consent, only my willingness, my loving agreement, to be good for me, to do nothing but work for my benefit, to be unable to ever harm me. I have experienced on my body and on my soul that I needed sin very much, I needed lust, the desire for possessions, vanity, and needed the most shameful despair, in order to learn how to give up all resistance, in order to learn how to love the world, in order to stop comparing it to some world I wished, I imagined, some kind of perfection I had made up, but to leave it asit is and to love it and to enjoy being a part of it.--These, oh Govinda, are some of the thoughts which have come into my mind."

Siddhartha bent down, picked up a stone from the ground, and weighed it in his hand.

"This here," he said playing with it, "is a stone, and will, after a certain time, perhaps turn into soil, and will turn from soil into a plant or animal or human being. In the past, I would have said: This stone is just a stone, it is worthless, it belongs to the world of the Maja; but because it might be able to become also a human being and a spirit in the cycle of transformations, therefore I also grant it importance. Thus, I would perhaps have thought in the past. But today I think: this stone is a stone, it is also animal, it is also god, it is also Buddha, I do not venerate and love it because it could turn into this or that, but rather because it is already and always everything-- and it is this very fact, that it is a stone, that it appears to me now and today as a stone, this is why I love it and see worth and purpose in each of its veins and cavities, in the yellow, in the gray, in the hardness, in the sound it makes when I knock at it, in the dryness or wetness of its surface. There are stones which feel like oil or soap, and others like leaves, others like sand, and every one is special and prays the Om in its own way, each one is Brahman, but simultaneously and just as much it is a stone, is oily or juicy, and this is this very fact which I like and regard as wonderful and worthy of worship.--But let me speak no more of this. The words are not good for the secret meaning, everything always becomes a bit different, as soon as it is put into words, gets distorted a bit, a bit silly--yes, and this is also very good, and I like it a lot, I also very much agree with this, that this what is one man's treasure and wisdom always sounds like foolishness to another person."

Govinda listened silently.

第二天早晨,到了该出发上路的时候,戈文达有些犹豫地说:“在我继续赶路之前,席特哈尔塔,请允许我再提一个问题。你是否有一种自己的学说?你是否有一种必须遵循的、能帮助你生活和正直做人的信仰或学问?”

席特哈尔塔说:“你知道,亲爱的,当年我还是个年轻人,咱们在森林里跟苦行僧一起生活,我就开始怀疑种种学说和老师,并且离开了他们。现在我依然如此。可我后来还是有过不少老师。一个艳丽的名妓曾做过我很长时间的老师,一个富商也当过我的老师,此外还有几个赌徒。有一次,一个游方和尚也当了我的老师;他在朝圣路上发现我在树林里睡着了,就坐在我身边守护我。我也向他学习,感激他,十分感激。但是在这儿,我向这条河学得最多,还有就是我的师傅,船夫瓦苏代瓦。他是个很普通的人,这个瓦苏代瓦,他也不是思想家,但是他懂得应该懂的东西,就像戈塔马一样,他是一个完人,一个圣贤。”

戈文达说:“哦,席特哈尔塔,我觉得你还是总爱开玩笑。我相信你,知道你并没有追随一个老师。但即便没有一种学说,难道你自己就没有找到某些你特有的、帮助你生活的想法和认识?要是你能给我讲讲这些,会使我很开心。”

席特哈尔塔说:“我有过想法,对,有时也有过认识。有时我心中感受到知识,一个钟头或是一天,就像人在心中感受到生活一样。那是某些想法,但是我很难向你表达出来。瞧,戈文达,这就是我发现的一个想法:智慧是无法表达的。一个智者谋略表达的智慧,听起来却总像是愚蠢。”

“你在开玩笑吧?”戈文达问。

“我没有开玩笑。我说的正是我所发现的道理。知识可以传授,而智慧却不能。人可以发现它,可以体验它,可以享有它,可以用它来创造奇迹,但是却不能讲述和传授它。这便是我年轻时就已经预感到,并且离开了那些老师的原因。我发现了一个想法,戈文达,你又会以为是开玩笑或愚蠢行为,但其实是我最好的想法。那就是:每一个真理的反面也同样是真实的!也就是说,一个真理如果是片面的,那就要挂在嘴边说个不停。可以用思想去想或用言语去说的一切都是片面的。一切都是片面的,一切都不完整,一切都缺少完备、圆满和统一。戈塔马在讲经时谈到这个世界,不得不把它分为轮回和涅槃,立地成佛——可是你瞧:这个‘总有一天’是错觉,仅仅是比喻!罪人并没有走在成佛的路上,他并没有处在发展之中,尽管我们的思维不能把事物想象成别的样子。不,在罪人身上,现在和今天就已经有了将来的佛,他的前途已经全都在这里,你得在他身上、在你身上、在每个人身上敬奉这个未来的、可能的、隐形的佛。戈文达,尘世并不是不完善,或是正处在一条缓慢通向完美的路上:不,它在每一瞬间都是完美的,一切罪孽本身就已经蕴含着宽恕,所有小孩本身就已经蕴含着老人,所有婴儿都蕴含着死亡,所有濒死者都蕴含着永恒的生命。没有一个人能从另一个人身上看到他已在自己的路上走了多远,强盗和赌徒可能成佛,婆罗门则可能成为强盗。在深沉的冥想中有可能取消时间,把一切过去的、现在的和将来的生活都看作是同时的,于是一切都很好,一切都很完美,一切都属于婆罗门。因此,我觉得凡存在的都是好的,我觉得死跟生一样,罪孽跟圣洁一样,聪明跟愚蠢一样,一切都肯定如此,一切都只需要我的赞成,我的同意,我的欣然认可,因而对我来说是好的,决不会伤害我。我从自己的身体和心灵体会到,我十分需要罪孽,需要肉欲,需要追求财富,需要虚荣,需要最为可耻的绝望,以便学会放弃抗争,学会爱这个世界,不再拿它与某个我所希望的、臆想的世界相比,与一种我凭空臆造的完美相比,而是听其自然,爱它,乐意从属于它。哦,戈文达,这就是我想到的一些想法。”

席特哈尔塔弯下腰,从地上捡起一块石头,拿在手里掂了掂。

“这玩意儿,”他轻松地说,“是一块石头,它过了一定的时候也许会变成泥土,又偷漏经土变成植物,或者变成动物或人。而过去我会说:‘这块石头仅仅是一块石头。它毫无价值,属于玛雅的世界。但是,因为它说不定在变化的循环中也会变成人和鬼,所以我也赋予它价值。’过去我大概会这么想。但今天我却想:这块石头是石头,它也是动物,也是神,也是佛,我并非因为它将来会变成这个或那个才敬重和热爱它,而是因为它早就一直是一切——而它是石头,现如今在我眼前呈现为石头,正是这一点,正是因为这个,我才爱它,从它的每一个纹路和凹坑口里,从黄色,从灰色,从硬度,从我叩击它时发出的响声,从它表面的干燥或潮湿中,看到它的价值和意识。有些石头摸着像油脂或肥皂,中有一些像树叶,还有一些像沙子,每一块都有其特点,以其特有的方式念诵‘唵’,每一块都是婆罗门,但同时又确实是石头,滑溜溜或者油腻腻,正是这一点叫我喜欢,我觉得奇妙,值得崇拜。——不过,我就别再多说了吧。话语对于隐蔽的含义不利,说出来总会有点儿不同,有点儿走样,有点儿愚蠢——是的,就是这点也很好,令我喜欢,我完全同意:一个人的宝贝与智慧,另一个人听起来却总是愚蠢。”

戈文达默不作声地听着。

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

作者简介:

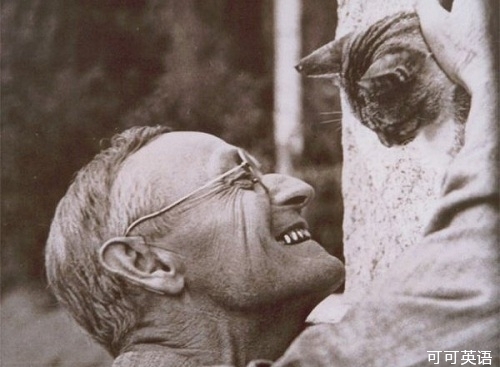

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

豆瓣热门书评:席特哈尔塔与乔达摩悉达多

来自: 宠物跳蚤

不算评论,只是想谈一个简单的问题。

因为这种情况在我读杨玉功翻译的《悉达多》的时候也发生过。最初总是在“悉达多就是佛教的创始人”这个语境中,直到悉达多去拜访佛陀,也就是乔达摩的时候,我开始困惑不已。

在这个方面,不能不说译者杨玉功应该负主要责任。他的那篇颇有些自鸣得意的序我印象很深刻,一种少年得意之情充斥其中:二十多岁就把全书译完,现在再看觉得还是没有什么不妥的地方;对旧翻译书名音译(即《席特哈尔塔》)有所不满,更指出了一处错误“潜入水中”,他说应翻译为“在水面行走”。恰恰是他得意的书名《悉达多》,误导了很多人,认为这是佛教创始人的一篇西方作家所做的传记,甚至连一些我国出的西方文学史(特别是一部五卷本的德国文学史)谈到此书时也作是评。

实际上如此吗?

当然不!下面从几个方面来说明。

为了区分,《悉达多》一书的主人公悉达多,我们用旧翻译,即音译,席特哈尔塔。

从现实的层面讲,乔达摩悉达多,也就是佛教的创始人应当为其全名,而悉达多仅仅是名而已。书中写的婆罗门贵族青年席特哈尔塔仅仅和佛祖重名(作者是否有意另作讨论),就像张伟,刘伟,王伟一样,怎么能就此认为是佛教创始人呢?而且佛祖乔达摩悉达多出身为印度四大种姓的另一个:刹帝利。

从书中的内容讲,席特哈尔塔曾经拜访了已经尊为佛祖的乔达摩悉达多,作者分明把两人区别开来,怎么可以再将两者混淆?佛祖的传道首先是在鹿野苑,而席特哈尔塔也就是本书的主人公拜访并师从之后,认为乔达摩悉达多是位伟人,但其学说或者体悟并不能满足自己的心灵——这一点很重要,下面马上提到,希望大家注意。

再从思想的深度来讲,《悉达多》(《席特哈尔塔》)之所以会风靡全世界,假如它只是一本佛祖的西方传记,恐怕根本达不到那种动人心魄的效果,事实上,从作者自身思想发展来看,他虽然对印度的哲学很有兴趣,并非真的信服,反而越到后来越是靠近中国的古代哲学,比如老子。

纵观黑塞一生的创作历程,会发现作者不断地在探讨的并非是某一种宗教或者学说让书中的主人公乃至书后的黑塞本人信服,而是这些东西或启发,或阻碍主人公作为一个“人”对自身心灵在现实世界中的探寻。黑塞本人在现实生活中也是这么做的,他没有埋头在书房里冥思苦想,而是走了很多地方,在最接近大自然的地方独自居住,经历了三次婚姻,遭遇无数的误解,他不但写小说,写诗歌,而且还画画。从《盖特路德》《罗斯哈尔德》到《席特哈尔塔》到《纳尔齐斯和歌尔德蒙》,哪一个主人公不是在现实生活中不断地追寻?不断经历生活?如果将《席特哈尔塔》理解为佛祖的传记,真是把黑塞的视野极大的狭隘化了。

我们再重温一下席特哈尔塔所经历过的吧:沙门,静修,物质之富,欲望之淫,亲情之痛,自然之歌。这些是佛教所能概括的吗,难道他最后皈依的是佛教吗?不,他最后皈依的是自然,连皈依佛教静修多年的旧友侨文达也崇敬地望着他,难以理解席特哈尔塔如何达到这样的境界。

“他深深地鞠躬,一躬到地,向端坐不动的席特哈尔塔敬礼,席特哈尔塔的笑容让他忆起了自己一生中曾经爱过的一切,忆起了自己一生中认为宝贵和神圣的一切。”

我们不禁想到歌尔德蒙弥留中追问纳尔齐斯:“可你将来想怎么死呢,纳尔齐斯,你没有母亲?人没有母亲就不能爱,没有母亲也不能死啊!”

这并非无欲无求的佛心,而是不可言传的大道。

附:黑塞与道的关系需另论,此文目的在于辨明乔达摩悉达多和席特哈尔塔绝非一人,并且此书绝非佛祖传记。