(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

The crickets were screaming on Thursday and the sky, stripped of blue, was white hot at eleven in the morning. Sethe was badly dressed for the heat, but this being her first social outing in eighteen years, she felt obliged to wear her one good dress, heavy as it was, and a hat. Certainly a hat. She didn't want to meet Lady Jones or Ella with her head wrapped like she was going to work.

The dress, a good-wool castoff, was a Christmas present to Baby Suggs from Miss Bodwin, thewhitewoman who loved her. Denver and Paul D fared better in the heat since neither felt theoccasion required special clothing. Denver's bonnet knocked against her shoulder blades; Paul Dwore his vest open, no jacket and his shirt sleeves rolled above his elbows. They were not holdinghands, but their shadows were. Sethe looked to her left and all three of them were gliding over thedust holding hands. Maybe he was right. A life. Watching their hand holding shadows, she was embarrassed at being dressed for church.

The others, ahead and behind them, would think she was putting on airs, letting them know thatshe was different because she lived in a house with two stories; tougher, because she could do andsurvive things they believed she should neither do nor survive. She was glad Denver had resistedher urgings to dress up — rebraid her hair at least.

But Denver was not doing anything to make this trip a pleasure. She agreed to go — sullenly —but her attitude was "Go 'head. Try and make me happy." The happy one was Paul D. He saidhowdy to everybody within twenty feet. Made fun of the weather and what it was doing to him,yelled back at the crows, and was the first to smell the doomed roses. All the time, no matter what they were doing — whether Denver wiped perspiration from her forehead or stooped to retie hershoes; whether Paul D kicked a stone or reached over to meddle a child's face leaning on its mother's shoulder — all the time the three shadows that shot out of their feet to the left held hands.

Nobody noticed but Sethe and she stopped looking after she decided that it was a good sign. A life. Could be.

Up and down the lumberyard fence old roses were dying. The sawyer who had planted themtwelve years ago to give his workplace a friendly feel — something to take the sin out of slicingtrees for a living — was amazed by their abundance; how rapidly they crawled all over the stakeand-post fence that separated the lumberyard from the open field next to it where homeless menslept, children ran and, once a year, carnival people pitched tents. The closer the roses got to death,the louder their scent, and everybody who attended the carnival associated it with the stench of therotten roses. It made them a little dizzy and very thirsty but did nothing to extinguish the eagernessof the coloredpeople filing down the road. Some walked on the grassy shoulders, others dodged thewagons creaking down the road's dusty center. All, like Paul D, were in high spirits, which thesmell of dying roses (that Paul D called to everybody's attention) could not dampen. As theypressed to get to the rope entrance they were lit like lamps.Breathless with the excitement ofseeing white people loose: doing magic, clowning, without heads or with two heads, twenty feettall or two feet tall, weighing a ton, completely tattooed, eating glass, swallowing fire, spittingribbons, twisted into knots, forming pyramids, playing with snakes and beating each other up.

All of this was advertisement, read by those who could and heard by those who could not, and thefact that none of it was true did not extinguish their appetite a bit. The barker called them and theirchildren names ("Pickaninnies free!") but the food on his vest and the hole in his pants rendered itfairly harmless. In any case it was a small price to pay for the fun they might not ever have again.

Two pennies and an insult were well spent if it meant seeing the spectacle of whitefolks making aspectacle of themselves. So, although the carnival was a lot less than mediocre (which is why itagreed to a Colored Thursday), it gave the four hundred black people in its audience thrill uponthrill upon thrill.

星期四,蟋蟀鼓噪着,剥去了蓝色的天空在上午十一点是白热的。天气这么热,塞丝的穿着特别不舒服,可这是她十八年来头一回外出社交,她觉得有必要穿上她唯一的一条好裙子,尽管它沉得要命;还要戴上一顶帽子。当然要戴帽子。她不想在遇见琼斯女士或艾拉时还包着头,像是去上班。

这条纯羊毛收针的裙子是贝比?萨格斯的一件圣诞礼物,那个热爱她的白女人鲍德温小姐送的。丹芙和保罗?D谁也没觉得这种场合需要特别的衣着,所以在大热天里还好受些。丹芙的软帽总是碰着垫肩;保罗?D敞开马甲,没穿外套,把衬衫袖子卷到胳膊肘上。他们并没有彼此拉着手,可是他们的影子却拉着。塞丝朝左看了看,他们三个是手拉着手滑过灰尘的。也许他是对的。一种生活。她看着他们携手的影子,为自己这身去教堂的打扮而难为情。

前前后后的人会认为她是在摆架子,是让大家知道自己与众不同,因为她住在一栋两层楼房里;让大家知道自己更不屈不挠,因为她既能做又能经受他们认为她不能做也不能经受的事情。她很高兴丹芙拒绝了打扮一番的要求———哪怕重新编一下辫子。

然而丹芙不愿付出任何努力,给这次出行增加一点愉快气氛。她同意去了———闷闷不乐地———但她的态度是“去呗。试试哄我高兴起来”。高兴的是保罗?D。他向二十英尺之内的每一个人打招呼,拿天气以及天气对他的影响开玩笑,向乌鸦们呱呱回嘴大叫,并且头一个去嗅凋萎的玫瑰花。自始至终,不论他们在干什么———无论是丹芙在擦额头上的汗、停下来系鞋带,还是保罗?D在踢石子、伸手去捏一个妈妈肩上的娃娃的脸蛋———从他们脚下向左投射的三个人影都一直拉着手。

除了塞丝,没有人注意到,而她一旦认定了那是个好兆头,便停下来看了又看。一种生活。也许吧。

贮木场围栏的上上下下有玫瑰在衰败。十二年前种下它们的那个锯木工———也许是为了让他的工作场所显得友好,为了消除以锯树为生的罪恶感———对它们的繁荣感到震惊;它们如此迅速地爬满了栅栏,把贮木场同旁边开阔的田野隔开;田野上,无家可归的人在那里过夜,孩子们在那里跑来跑去,一年一度,杂耍艺人在那里搭起帐篷。玫瑰愈临近死亡,气味便愈发浓烈,所有参加狂欢节的人都把节日同腐败玫瑰的臭气联系起来。这气味让他们有点头晕,而且异常干渴,却丝毫没有熄灭大路上络绎不绝的黑人们的热情。有的走在路肩的青草上,其余的则躲闪着路中央那些扬起灰尘、吱吱扭扭的大车。所有人都像保罗?D一样情绪高涨,连濒死玫瑰的气味(保罗?D使之引人注目)都不能抑制。他们挤进栏索入口的时候,像灯一样被点着了,都激动得屏住了呼吸,因为就要无拘无束地观看白人了:变魔术的、当小丑的、无头的或是双头的、二十英尺高或是二十英寸高的、一吨重的、全部文身的、吃玻璃的、吞火的、吐出打结的绸带的、筑金字塔的、耍蛇的,还有练把式的。

这一切都写在广告上,识字的念出来,不识字的就在一旁听着;尽管事实上都是些胡说八道,他们的兴致依然丝毫不减。招徕生意的骂着他们和他们的孩子(“小黑鬼免费!”),然而他马甲上的食物和裤子上的窟窿使得那些叫骂显得无伤大雅。无论如何,为了他们也许再不会得到的乐趣,这个代价太小了。

如果是为了观看白人们大出自己的洋相,两分钱加上一次侮辱花得值。所以,虽然这次狂欢节连平庸都够不上(那就是为什么一个“黑星期四”得到认可),它还是给了四百名黑人观众一个一个又一个的刺激。

背景阅读

本书简介:

《宠儿》是托妮·莫里森最震撼人心、最成熟的代表作,现已经成为当代文学史上不朽的经典,也是美国文学史上最畅销的作品之一。小说完成于1987年,1988年即获得美国普利策小说奖。2006年《纽约时报》召集125位知名作家、评论家、编辑及文坛泰斗等选出自己心目中“25年来最佳美国小说”,《宠儿》得票最高,名列第一。

“你的爱太浓了!”——一个不可能重复的故事!!!

女黑奴塞丝怀着身孕只身从肯塔基的奴隶庄园逃到俄亥俄,奴隶主循踪追至;为了使儿女不再重复自己做奴隶的悲惨命运,她毅然杀死了自己刚刚会爬的幼女宠儿……十八年后宠儿还魂重返人间,和塞丝、塞丝的女儿丹芙以及塞丝的情人保罗•D生活在同一幢房子里。她不但加倍地向母亲索取着爱,甚至纠缠和引诱保罗•D,不择手段地扰乱和摧毁母亲刚刚回暖的生活……全书充满苦涩的诗意和紧张的悬念。

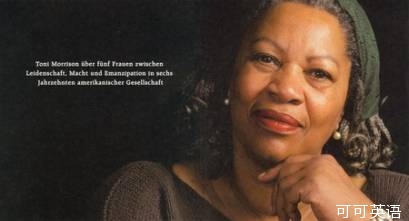

作者简介:

托妮·莫里森,美国当代最重要的女作家之一。1931年生于美国俄亥俄州,曾担任兰登书屋编辑、资深编辑,1989年起任普林斯顿大学教授。主要代表作有《最蓝的眼睛》、《秀拉》、《所罗门之歌》、《宠儿》、《爵士乐》、《天堂》等,曾获美国普利策小说奖、美国图书评论协会奖等多项大奖。1993年获诺贝尔文学奖,是历史上得此殊荣的唯一黑人女作家。