(单词翻译:单击)

双语小说

“We are honored to welcome the son of a man such as yourself into our family,” he said. “Your reputation precedes you. I was your humble admirer in Kabul and remain so today. We are honored that your family and ours will be joined.

“Amirjan, as for you, I welcome you to my home as a son, as the husband of my daughter who is the noor of my eye. Your pain will be our pain, your joy our joy. I hope that you will come to see your Khala Jamila and me as a second set of parents, and I pray for your and our lovely Soraya jan’s happiness. You both have our blessings.”

Everyone applauded, and with that signal, heads turned toward the hallway. The moment I’d waited for.

Soraya appeared at the end. Dressed in a stunning winecolored traditional Afghan dress with long sleeves and gold trimmings. Baba’s hand took mine and tightened. Khanum Taheri burst into fresh tears. Slowly, Soraya caine to us, tailed by a procession of young female relatives.She kissed my father’s hands. Sat beside me at last, her eyes downcast.The applause swelled.

ACCORDING TO TRADITION, Soraya’s family would have thrown the engagement party the Shirini-khori---or “Eating of the Sweets” ceremony. Then an engagement period would have followed which would have lasted a few months. Then the wedding, which would be paid for by Baba.

We all agreed that Soraya and I would forgo the Shirini-khori. Everyone knew the reason, so no one had to actually say it: that Baba didn’t have months to live.

Soraya and I never went out alone together while preparations for the wedding proceeded--since we weren’t married yet, hadn’t even had a Shirini-khori, it was considered improper. So I had to make do with going over to the Taheris with Baba for dinner. Sit across from Soraya at the dinner table. Imagine what it would be like to feel her head on my chest, smell her hair. Kiss her. Make love to her.

Baba spent $35,000, nearly the balance of his life savings, on the awroussi, the wedding ceremony. He rented a large Afghan banquet hail in Fremont--the man who owned it knew him from Kabul and gave him a substantial discount. Baba paid for the ??chi las, our matching wedding bands, and for the diamond ring I picked out. He bought my tuxedo, and my traditional green suit for the nika--the swearing ceremony. For all the frenzied preparations that went into the wedding night--most of it, blessedly, by Khanum Taheri and her friends-- I remember only a handful of moments from it.

I remember our nika. We were seated around a table, Soraya and I dressed in green--the color of Islam, but also the color of spring and new beginnings. I wore a suit, Soraya (the only woman at the table) a veiled long-sleeved dress. Baba, General Taheri (in a tuxedo this time), and several of Soraya’s uncles were also present at the table. Soraya and I looked down, solemnly respectful, casting only sideway glances at each other. The mullah questioned the witnesses and read from the Koran. We said our oaths. Signed the certificates. One of Soraya’s uncles from Virginia, Sharif jan, Khanum Taheri’s brother, stood up and cleared his throat. Soraya had told me that he had lived in the U.S. for more than twenty years. He worked for the INS and had an American wife. He was also a poet. A small man with a birdlike face and fluffy hair, he read a lengthy poem dedicated to Soraya, jotted down on hotel stationery paper. “Wah wah, Sharifjan!” everyone exclaimed when he finished.

I remember walking toward the stage, now in my tuxedo, Soraya a veiled pan in white, our hands locked. Baba hobbled next to me, the general and his wife beside their daughter. A procession of uncles, aunts, and cousins followed as we made our way through the hail, parting a sea of applauding guests, blinking at flashing cameras. One of Soraya’s cousins, Sharif jan’s son, held a Koran over our heads as we inched along. The wedding song, ahesta boro, blared from the speakers, the same song the Russian soldier at the Mahipar checkpoint had sung the night Baba and I left Kabul:Make morning into a key and throw it into the well,Go slowly, my lovely moon, go slowly. Let the morning sun forget to rise in the east, Go slowly, my lovely moon, go slowly.

I remember sitting on the sofa, set on the stage like a throne, Soraya’s hand in mine, as three hundred or so faces looked on. We did Ayena Masshaf, where they gave us a mirror and threw a veil over our heads, so we’d be alone to gaze at each other’s reflection. Looking at Soraya’s smiling face in that mirror, in the momentary privacy of the veil, I whispered to her for the first time that I loved her. A blush, red like henna, bloomed on her cheeks.

I picture colorful platters of chopan kabob, sholeh-goshti, and wild-orange rice. I see Baba between us on the sofa, smiling. I remember sweat-drenched men dancing the traditional attan in a circle, bouncing, spinning faster and faster with the feverish tempo of the tabla, until all but a few dropped out of the ring with exhaustion. I remember wishing Rahim Khan were there. And I remember wondering if Hassan too had married. And if so, whose face he had seen in the mirror under the veil? Whose henna-painted hands had he held?

“像你这样的男人的儿子成为我们的家人,我们很荣幸。”他说,“你声誉卓著,在喀布尔,我就是你谦卑的崇拜者,今天也是如此。你家和我家结成姻亲,这让我们觉得荣幸。”

“亲爱的阿米尔,至于你,我欢迎你到我的家里来,你是我们的女婿,是我掌上明珠的丈夫。今后我们休戚与共。我希望你能够将亲爱的雅米拉和我当成你的父母,我会为你和亲爱的索拉雅祷告,愿你们幸福。我们祝福你们俩。 ”

每个人鼓起掌来,在掌声中,人们把头转向走廊。那一刻我等待已久。索拉雅在那端出现。

她穿着酒红色的传统阿富汗服装,长长的袖子,配着黄金镶饰,真是惊艳夺目。爸爸紧紧抓着我的手。塔赫里太太又哭了。索拉雅慢慢地向我们走来,身后跟着一群年轻的女性亲戚。她亲了亲爸爸的手。终于坐在我身边,眼光低垂。掌声响起。

根据传统,索拉雅家里会举办订婚宴会,也就是所谓“食蜜”仪式。之后是订婚期,一连持续几个月。随后是婚礼,所有费用将由爸爸支付。

我们全部人都同意索拉雅和我省略掉“食蜜”仪式。原因大家都知道,虽然没人真的说出来:爸爸没几个月好活了。

在筹备婚礼期间,索拉雅和我从无独处的机会——因为我们还没有结婚,甚至连订婚都没有,那于礼不合。所以我只好满足于跟爸爸一起,到塔赫里家用晚餐。晚餐桌上,索拉雅坐在我对面。我想像着她把头放在我胸膛上,闻着她的秀发,那该是什么感觉呢?我想像着亲吻她,跟她做爱。

为了婚礼,爸爸花了三万五千美元,那几乎是他毕生的积蓄。他在弗里蒙特租了个很大的阿富汗宴会厅,老板是他在喀布尔的旧识,给了他优惠的折扣。爸爸请来了乐队,给我挑选的钻石戒指付款,给我买燕尾服,还有在誓约仪式要穿的传统绿色套装。在为婚礼之夜所做的全部乱糟糟的准备一幸好多数由塔赫里太太和她的朋友帮忙——中,我只记得屈指可数的几件事。

我记得我们的誓约仪式。大家围着一张桌子坐下,索拉雅和我穿着绿色的衣服——伊斯兰的颜色,但也是春天和新起点的颜色。我穿着套装,索拉雅(桌子上惟一的女子)蒙着面,穿长袖衣服。爸爸、塔赫里将军(这回他穿着燕尾服)还有索拉雅几个叔伯舅舅也坐在桌子上。索拉雅和我低着头,表情神圣而庄重,只能偷偷斜视对方。毛拉向证人提问,读起《可兰经》。我们发誓,在结婚证书上签名。索拉雅的舅舅,塔赫里太太的兄弟,来自弗吉尼亚,站起来,清清他的喉咙。索拉雅曾告诉过我,他在美国生活已经超过二十年。他在移民局工作,娶了个美国老婆。他还是个诗人,个子矮小,鸟儿似的脸庞,头发蓬松。他念了一首献给索拉雅的长诗,那是草草写在酒店的信纸上。“哇!哇!亲爱的沙利夫! ”他一念完,每个人都欢呼起来。

我记得走向台上的情景,当时我穿着燕尾服,索拉雅蒙着面,穿着白色礼服,我们挽着手。爸爸紧挨着我,将军和他太太在他们的女儿那边,身后跟着一群亲戚,我们走向宴会厅。两旁是鼓掌喝彩的宾客,还有闪个不停的镜头。我和索拉雅并排站着,她的表弟,亲爱的沙利夫的儿子,在我们头上举起《可兰经》。扬声器传来婚礼歌谣,慢慢走,就是爸爸和我离开喀布尔那天晚上,玛希帕检查站那个俄国兵唱的那首。将清晨化成钥匙,扔到水井去慢慢走,我心爱的月亮,慢慢走让朝阳忘记从东方升起慢慢走,我心爱的月亮,慢慢走

我记得我们坐在沙发上,舞台上那对沙发好像王位,索拉雅拉着我的手,大约三百位客人注视着我们。我们举行另外的仪式。在那儿,人们拿给我们一面镜子,在我们头上覆上一条纱巾,留下我们两个凝望彼此在镜子中的容颜。看到镜子中索拉雅笑靥如花,我第一次低声对她说我爱她。一阵指甲花般的红晕在她脸庞绽放。

我记得各色佳肴,有烤肉,炖肉饭,野橙子饭。我看见爸爸夹在我们两个中间,坐在沙发上,面带微笑。我记得浑身大汗的男人围成一圈,跳着传统舞蹈,他们跳跃着,在手鼓热烈的节拍之下越转越快,直到有人精疲力竭,退出那个圆圈。我记得我希望拉辛汗也在。并且,我还记得,我寻思哈桑是不是也结婚了。如果是的话,他蒙着头巾,在镜子中看到的那张脸是谁呢?他手里握着那涂了指甲花的手是谁的?

作品周边

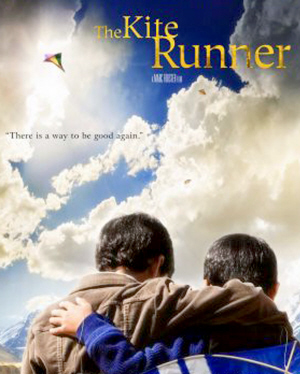

内容简介

12岁的阿富汗富家少爷阿米尔与仆人哈桑情同手足。然而,在一场风筝比赛后,发生了一件悲惨不堪的事,阿米尔为自己的懦弱感到自责和痛苦,逼走了哈桑,不久,自己也跟随父亲逃往美国。

成年后的阿米尔始终无法原谅自己当年对哈桑的背叛。为了赎罪,阿米尔再度踏上暌违二十多年的故乡,希望能为不幸的好友尽最后一点心力,却发现一个惊天谎言,儿时的噩梦再度重演,阿米尔该如何抉择?

故事如此残忍而又美丽,作者以温暖细腻的笔法勾勒人性的本质与救赎,读来令人荡气回肠。

作者简介

卡勒德·胡赛尼(Khaled Hosseini),1965年生于阿富汗喀布尔市,后随父亲迁往美国。胡赛尼毕业于加州大学圣地亚哥医学系,现居加州。“立志拂去蒙在阿富汗普通民众面孔的尘灰,将背后灵魂的悸动展示给世人。”著有小说《追风筝的人》(The Kite Runner,2003)、《灿烂千阳》(A Thousand Splendid Suns,2007)、《群山回唱》(And the Mountains Echoed,2013)。作品全球销量超过4000万册。2006年,因其作品巨大的国际影响力,胡赛尼获得联合国人道主义奖,并受邀担任联合国难民署亲善大使。

精选评论

热门评论

对友谊最大的误解,就是认为它是万能的(来自豆瓣网友:谢长留)

我时常幻想自己是来自未来的,这样,有一天我面对未来某一时刻的突然变化,就会更从容,面对陈年往事也会更慷慨。但,我更适合平庸,如寻常人一样琐碎繁杂的生活,对时间的细枝末节斤斤计较。

既然无法预知未来,那么人更多的开始依赖回忆,甚至靠那些零星琐碎的回忆支撑往后的日子,有些回忆很美好,有些回忆很心酸,有些回忆让人长大,有些回忆让人显得很无知,有些回忆慢慢泛黄,有些回忆仿佛就在昨天。有些故事也总是从儿时的回忆展开。

我对阿富汗以及周边连年征战的国家和他们的历史毫无兴趣,对我而言,那里的人民是可怜的,那里的政府是可悲的,所以当《追风筝的人》这个故事一点一点展现在我面前的时候,我并没准备好接受一个平静的,也曾春暖花开,羊肉串香飘整条街的画面,更没想到那里的孩子也可以无忧无虑的追逐风筝。

所以当身为少爷的阿米尔和他的仆人哈桑情同手足的画面一出现,所有读者不禁感叹,少年时的友谊是那么充满力量,干净而持久的。他们总是并肩而行,每当阿米尔被人欺负的时候,哈桑总是义无反顾的站出来保护,很多人说这是哈桑天生的奴性,这种观点我不赞同,我看见他们之间分明有一道友谊的光芒在闪耀。

当阿米尔问哈桑为什么确定自己一定会知道被切断绳线的风筝的掉落地的时候,哈桑肯定的对阿米尔说,我就是知道,然后反问,我什么时候骗过你。阿米尔轻声说,我怎么知道有没有骗过我。哈桑发誓,为了你,我宁可啃烂泥。阿米尔进一步确定,你真的会为我啃烂泥?哈桑坚定的说,我肯定,然后又说,但是你又怎么能忍心让我啃烂泥。所以读者心中所向往的也就是我们每个人心中那个潮湿的童年印象,总是和自己最亲密的伙伴,席地而坐,互相盟誓,发誓为对方,甘愿上刀山下火海。就如同哈桑洋溢着笑脸对阿米尔说的那样:为你,千千万万遍。

然而事实上却是这样的:他是主人,他是仆人;他是普什图,他是哈扎拉;他是逊尼派,他是什叶派,从他们出生的那一刻起,他们的命运就被这些他们所不能理解的标签所分隔开来,尽管他们是亲密无间的朋友,尽管他们事实上拥有同一位父亲。无论是平凡的阿米尔和哈桑,还是高高在上的查希尔国王或者卡尔扎伊,都不得不接受社会为他们预定的座位——阿米尔不再是阿米尔,哈桑也不再是哈桑,他们必须戴上社会分给他们的面具。

哈桑总是说“为你,千千万万遍”,而生性懦弱的阿米尔却选择沉默冷酷的逃避,这样的悲剧性结果并不单单是个性差异所造成的,在这些年少无知的孩子的潜意识里早已被灌输了相应于自身社会地位的“应该”与“不应该”,一个哈扎拉仆人理应为主人尽忠,而高贵的普什图少爷不值得为一个卑贱的哈扎拉仆人冒任何风险。

“阿米尔和哈桑,喀布尔的统治者”,这样的誓言只能是石榴树下的童话,“王子与贫儿”不可能成为兄弟,因为他们命中注定不平等。包括二十年后,阿米尔重返阿富汗的自我救赎行为,也只不过是在获知自己与哈桑的同父异母兄弟关系之后对身世的无奈认可,也就是说,他仍然没有证明自己已经找到了“重新成为好人的路”。

我们少年的时候,总是意气风发,三五结伴,促膝长谈。那是在我们其乐融融的环境中构建的虚拟场景,属于物理学讲究的理想状态,然而在残酷的现实面前,在微弱的友谊遇到挑战的时刻,只要有一方露出破绽,友谊的桥梁必然坍塌。

于是当阿米尔在看到哈桑被大一些的孩子欺负甚至猥亵的时候,他选择沉默和逃避;与此同时,哈桑却为了阿米尔的风筝坚定不动摇的和对手较量,对手残忍的揭示阿米尔和哈桑之间的主仆关系,哈桑大声反驳说两个人是朋友。躲在角落里不敢出现的阿米尔听到这句话不但没有一点激励也没有丝毫感动,他心底里的怯懦终于将他的灵魂吞噬,于是悲剧发生。

这就是我们对友谊最大的误解,认为它是万能的。

即使是存在这样的问题,《追风筝的人》也还是一本出色的小说。主和仆、贵族和贱民、朋友和兄弟,历史和现实,种种转变都被刻画得生动而细腻。放在历史的宏大背景下,更洞见人生和人性的复杂。

友谊和爱。

是在困难之中由弱变强的柔韧派还是在权衡利弊之中土崩瓦解的懦弱派。

谁敢真的站出来举起右手发誓,我从来没有辜负过任何一段纯粹的友谊,谁敢真的抬头挺胸说自己对朋友忠心不二。

我们总是太自信,对友谊误解,对自己的爱误解,对不可能的事信以为真。