(单词翻译:单击)

From the very beginning, Coca-Cola had a drug problem.

可口可乐诞生源于一个药物问题。

The brand’s founder, Atlanta pharmacist John Stith Pemberton, was addicted to morphine, a narcotic many suspected Pemberton began using after suffering a series of debilitating wounds while defending the city of Columbus, Georgia, during the Civil War. By the 1880s, Pemberton was not well, and he was also hurting financially. In 1872, Pemberton filed for bankruptcy and a few years later watched helplessly when two fires ravaged his Atlanta business. In 1886, he had finally clawed his way out of debt but was still strapped for cash.

可口可乐(Coca-Cola)品牌的创始人是亚特兰大药剂师约翰o彭伯顿。他在美国内战中参加过保卫佐治亚州哥伦布市的战斗,据很多人猜测,因为参战导致伤病缠身,他染上了吸食吗啡(一种麻醉剂)的恶习。19世纪80年代,彭伯顿的健康状况非常糟糕,同时经济上也遭受打击。1872年,彭伯顿申请破产。几年后,他又眼睁睁地看着自己在亚特兰大的生意在两场大火中被付之一炬。1886年,他终于摆脱债务缠身的窘境,但是手头依然缺钱。

That was the year Pemberton introduced Atlanta to Coca-Cola. Pemberton patterned his drink after a French patent medicine called Vin Mariani, a Bordeaux wine mixed with coca leaves, which had become quite popular in international markets by the end of the 1870s, and why not? Here was a drink that was essentially cocaine-laced wine, inducing quite a buzz for the habitual consumer. All sorts of luminaries testified to its restorative properties, including U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant and Pope Leo XIII.

就在这一年,彭伯顿在亚特兰大推出了可口可乐。19世纪70年代末,一种叫做Vin Mariani的法国专利药物在国际市场非常畅销,这种药是由混合了古柯树叶的波尔多葡萄酒制成。彭伯顿的可口可乐就是仿照这种药物饮料而来。为什么不呢?这种药物饮料实际上是一种带可卡因成分的葡萄酒,习惯了这种味道的消费者对其趋之若鹜。众多大牌名人认为该饮料有滋补复元之功效,其中包括美国总统尤里西斯o辛普森o格兰特和罗马教皇利奥十三世。

Cash-poor Pemberton believed it made smart business sense to create a knockoff of this popular beverage, which is exactly what he did, selling his own French Wine of Coca in 1885. The problem was, Protestant clamoring for prohibition led to citywide restrictions on alcohol consumption in Atlanta, forcing Pemberton to replace the wine with carbonated water. Thus, Coca-Cola became a kind of temperance drink in 1886.

为钱所困的彭伯顿看到了商机,认为仿制这款热门饮料一定是个不错的生意。而他真就这么做了,1885年,他开始售卖自己的饮料品牌:法国古柯葡萄酒(French Wine of Coca)。但是问题是,当时的清教徒呼吁禁酒,导致亚特兰大全城推行禁酒令,于是彭伯顿不得不将葡萄酒换成汽水。于是在1886年,就有了这种无酒精饮料可口可乐。

The decision to switch to water was more than just an expedient solution to a prohibition problem: it allowed Pemberton to outsource roughly 80% of his product’s volume onto others. That’s because it was soda fountain operators who mixed the water—at least five ounces per one ounce of syrup—into Pemberton’s finished beverages. All Pemberton sold was a dark, syrupy concentrate, which allowed him to save enormous amounts of money on transportation costs. Of course, the soda fountain water ultimately came from the municipal tap.

换成汽水不仅仅是应对禁酒令的权宜之计,这也让彭伯顿得以将约80%的产品生产外包出去。冷饮店的经营者们需要做的,仅仅是按一定比例将水兑入彭伯顿制成的饮料(至少五盎司水兑一盎司糖浆)。如此一来,彭伯顿出售的就只是黑色的浓缩糖浆,从而可以节省大笔运输费用。当然,冷饮店冰柜里的水就是自来水。

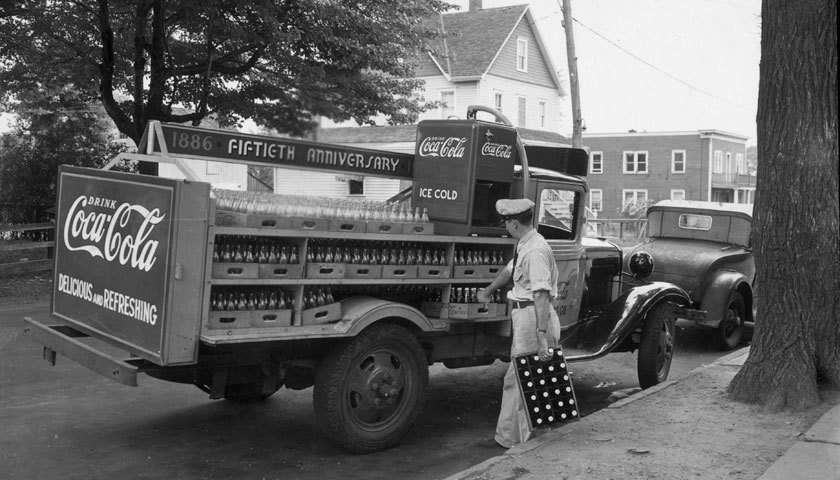

This model continued under Pemberton’s successor, Atlanta pharmacist Asa Candler, who signed the first bottling franchise contracts for Coca-Cola in 1899. Initially hesitant to approve this distribution method—considering the rudimentary nature of most bottling operations at the time—Candler came to see that bottling enabled Coke to reach rural markets far removed from city centers. What made the deal even sweeter was the fact that independent businessmen in small towns covered the tab for this expansion. Bottlers fronted the capital to buy the machinery, packaging, and municipal water, as well as the trucks and tires that spread Coke’s syrup through the nation’s commercial arteries.

1899年,亚特兰大药剂师艾萨o钱德勒与可口可乐签订了首份装瓶授权合同,并接管公司,之后沿用了这种经营模式。钱德勒开始并不同意采用这种分销模式,因为当时大多数装瓶业务很不成熟,但是他后来认识到,装瓶分销可以让产品深入远离市中心的农村市场。这种经营模式更大的好处在于:位于小城镇的独立企业主们自掏腰包助力市场扩张。装瓶公司们垫款购买机器,支付包装、市政用水以及卡车和轮胎的费用,可口可乐的糖浆也由此迅速渗透到全国各地的商业大动脉。

But Coke’s outsourcing strategy didn’t stop there. On the supply side, Coke also shunned ownership of factories and plants. The company did not own sugar plantations in the Caribbean, high-fructose corn syrup wet mills in the Midwest, or decaffeination facilities in the Southeast. Rather, the company relied on a host of independent businesses—the Monsanto Chemical Company, Cargill, Hershey Chocolate Company, among many others—to mine, process, and refine the critical ingredients that went into its finished beverages. In short, Coke was averse to vertical business integration, and instead acted as a kind of commodity broker, making money by transferring materials from independently owned producers and distributors.

然而,可口可乐的外包战略并没有就此止步。在供应方面,可口可乐还尽量避免持有工厂和厂房。比如,该公司既没有在加勒比海拥有糖种植园,或在中西部持有高果糖玉米糖浆的湿磨厂,也没有在东南部持有脱咖啡因的设施。相反,公司依赖大量独立的企业,如孟山都化学公司(Monsanto Chemical Company)、嘉吉公司(Cargill)、好时公司(Hershey Chocolate Company)等等,来对成品饮料中的关键成分进行采掘、加工和提炼。总之,可口可乐不喜欢垂直的业务整合,而是作为某种商品经纪人,通过在独立经营的生产商和分销商之间传输材料来赚钱。

I call this money-making approach Coca-Cola capitalism. Coke followed this path throughout the 20th century. It involved getting others, whether it was government-owned water works or vertically integrated sugar refineries, to invest in the production and distribution systems needed to turn the “Real Thing” into a real thing. What made Coke great, in other words, was not really what it did, but what it didn’t do. It proved incredibly adept at getting independent businesses and local governments to bear the majority of the costs of producing and distributing its products.

我将这种赚钱之道称之为“可口可乐资本主义”。整个20世纪,可口可乐都是这么做的。它让其他人,不论是政府的自来水厂还是垂直整合的炼糖厂,都投入生产和分销系统,共同完成“Real Thing(真家伙)”(来自可口可乐的广告语)的生产。换言之,真正让可口可乐成为一家伟大企业的,不是它做了什么,而是它没有做什么。事实证明,可口可乐长袖善舞,擅于调动其他企业和当地政府,为其承担产品的大部分生产和分销成本。

Take municipal recycling systems. Here was a publicly financed program that helped soft drink companies expand their productive capacity on the taxpayer’s dime. Once again, Coke did little of the work, letting municipalities and private citizens invest in elaborate reclamation infrastructure in the 1980s and 1990s that conveniently brought copious quantities of packaging materials back to local centers near its corporate distributors. Rather than having to pay for the waste they produced, Coca-Cola received a kind of public subsidy that in the long run enabled them to continue to produce tremendous quantities of one-way, throwaway containers (72% of which, in the case of plastic PET containers, ends up in American landfills today). As it had with public water supplies, the company was simply tapping into another municipal stream, only this one contained packaging materials, not water.

以城市再循环系统为例,这是一个由纳税人出资帮助软饮料公司扩大生产力的公共资助计划。20世纪八九十年代,可口可乐又一次不费吹灰之力,让市政府和市民出资修建了精良的回收基础设施,让大批包装材料可以非常便利地回到公司分销商附近的当地回收中心。可口可乐公司不但没有为其生产的垃圾支付任何费用,甚至还享受了一项政府补贴,这项补贴从长远上帮助其不断生产数量巨大的一次性饮料包装(其中72%是PET塑料瓶,它们现在都躺在了美国的垃圾填埋场)。于是除了公共用水外,可口可乐公司动用了又一项公共资源,只不过这次不是水,而是包装材料。

Coca-Cola has not been the only company to follow this path to big profits. Software firms, such as Microsoft MSFT -0.25% , have made tremendous revenues selling its Office suite, relying on other businesses to produce expensive hardware that can turn Microsoft’s code into consumable products. You can find an extreme version of Coca-Cola capitalism on Wall Street, where brokers do not manage any kind production or distribution infrastructure but instead make money off transaction fees as commodities flow from one buyer to another.

用这种方法谋取暴利的不止可口可乐一家。像微软(Microsoft)这类软件公司,他们通过销售办公软件获取高额利润,但是依靠的是其他企业生产的昂贵硬件,从而将微软的编程变成消费品。在华尔街,你可以见到可口可乐资本主义的一个极端案例:股票经纪人从不管理任何生产或分销基础设施,而是通过商品在买家中的流通赚取交易费。

In short, Coca-Cola KO 0.36% capitalism has become the model for some of the most profitable firms of our time. This is what 21st century capitalism rewards.

简而言之,可口可乐资本主义已经成为这个时代最赚钱的一类企业模式。这就是21世纪资本主义的回报。

But the question remains: does this system benefit the public at large? The history of Coca-Cola reveals that the firm demands a great deal of public resources—recycling systems, subsidized municipal water, corn subsidies, etc.—and it is not at all clear that Coke transforms these investments into goods that serve the interests of the nation (do we really need more sugar water in a country in which over 30% of the population is obese?).

但是问题依然存在:这个系统能否惠及广大民众?可口可乐的发展史显示,该企业对公共资源的需求极大,例如回收系统、补贴性城市用水、玉米补贴等等,可口可乐公司把这些投资变成商品,但是我们却根本不清楚这是否利国利民(在一个肥胖人口超过总人口30%的国家,我们真的需要更多汽水么?)。

While Coca-Cola is shifting towards healthier drink options, especially bottled water, the price for providing this service should appear unconscionable to the informed consumer. Americans pay more than $4 for a gallon of Dasani water when they could easily enjoy the same quantity of clean water from their tap for a fraction of a cent. Perhaps our money could be better spent fixing public water systems—which currently need over $500 billion in repairs, according to the EPA—rather than purchasing Coke’s bottled water. After all, as Coke’s history makes clear, private citizens and Coca-Cola need public pipes to survive.

虽然可口可乐开始推出更健康的饮品选择,尤其是瓶装水,但是对于明智的消费者来说,其价格并不合理。一加仑Dasani矿泉水售价超过4美元,而拧开水龙头美国民众就可以喝上等量的净水,价格不过是几厘。与其购买可口可乐瓶装水,我们还不如把钱用在完善公共供水系统上。据美国环保署(EPA)估计,公共供水系统维修需要的费用超过5,000亿美元。毕竟,正如可口可乐的发展史清楚展示的,无论普通市民还是可口可乐公司,都是靠公共水管存活的。(财富中文网)