(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

Siddhartha laughed. "Once before, I have been looked upon today because of my clothes, I have been looked upon with distrust. Wouldn't you, ferryman, like to accept these clothes, which are a nuisance to me, from me? For you must know, I have no money to pay your fare."

"You're joking, sir," the ferryman laughed.

"I'm not joking, friend. Behold, once before you have ferried me across this water in your boat for the immaterial reward of a good deed. Thus, do it today as well, and accept my clothes for it."

"And do you, sir, intent to continue travelling without clothes?"

"Ah, most of all I wouldn't want to continue travelling at all. Most of all I would like you, ferryman, to give me an old loincloth and kept me with you as your assistant, or rather as your trainee, for I'll have to learn first how to handle the boat."

For a long time, the ferryman looked at the stranger, searching.

"Now I recognise you," he finally said. "At one time, you've slept in my hut, this was a long time ago, possibly more than twenty years ago, and you've been ferried across the river by me, and we parted like good friends. Haven't you've been a Samana? I can't think of your name any more."

"My name is Siddhartha, and I was a Samana, when you've last seen me."

"So be welcome, Siddhartha. My name is Vasudeva." You will, so I hope, be my guest today as well and sleep in my hut, and tell me, where you're coming from and why these beautiful clothes are such a nuisance to you."

They had reached the middle of the river, and Vasudeva pushed the oar with more strength, in order to overcome the current. He worked calmly, his eyes fixed in on the front of the boat, with brawny arms. Siddhartha sat and watched him, and remembered, how once before, on that last day of his time as a Samana, love for this man had stirred in his heart. Gratefully, he accepted Vasudeva's invitation. When they had reached the bank, he helped him to tie the boat to the stakes; after this, the ferryman asked him to enter the hut, offered him bread and water, and Siddhartha ate with eager pleasure, and also ate with eager pleasure of the mango fruits, Vasudeva offered him.

Afterwards, it was almost the time of the sunset, they sat on a log by the bank, and Siddhartha told the ferryman about where he originally came from and about his life, as he had seen it before his eyes today, in that hour of despair. Until late at night, lasted his tale.

Vasudeva listened with great attention. Listening carefully, he let everything enter his mind, birthplace and childhood, all that learning, all that searching, all joy, all distress. This was among the ferryman's virtues one of the greatest: like only a few, he knew how to listen. Without him having spoken a word, the speaker sensed how Vasudeva let his words enter his mind, quiet, open, waiting, how he did not lose a single one, awaited not a single one with impatience, did not add his praise or rebuke, was just listening. Siddhartha felt, what a happy fortune it is, to confess to such a listener, to burry in his heart his own life, his own search, his own suffering.

But in the end of Siddhartha's tale, when he spoke of the tree by the river, and of his deep fall, of the holy Om, and how he had felt such a love for the river after his slumber, the ferryman listened with twice the attention, entirely and completely absorbed by it, with his eyes closed.

席特哈尔塔笑了:“我今天已经因为这身衣服惹人注意过,让人猜疑过了。船夫呀,你是否愿意要我这身惹麻烦的衣服?因为你要知道,我没钱付你摆渡费呢。”

“先生是在开玩笑吧。”船夫笑道。

“我没有开玩笑,朋友。你瞧,你曾用你的船送我渡了一次河,没收钱。今天也还是照样吧,请收下我的衣服。”

“先生莫非要不穿衣服继续赶路?”

“啊,我现在最希望的是根本不用再赶路。船夫呀,最好你能给我一件旧围裙,收我做你的助手,更确切地说是做你的徒弟,因为我得先学会撑船才行。”

船夫久久地探询地注视着这个陌生人。

“现在我认出你来了。”他终于说道,“你在我的茅屋里睡过觉,那已经很久了,大概有二十多年了吧。当年我把你渡过河,然后咱们就像好朋友一样分手了。那时你不是沙门吗?你的名字我实在想不起来了。”

“我叫席特哈尔塔。上次你见到我时我确实是个沙门。”

“那么我欢迎你,席特哈尔塔。我叫瓦苏代瓦。我希望你今天还是做我的客人,睡在我的茅屋里,给我讲讲你从哪儿来,你的华丽衣服为什么成了你的累赘。”

他们已来到河中心,瓦苏代瓦加紧划桨,逆水前进。他用有力的胳臂平静地工作着,目光盯着船头。席特哈尔塔坐着看他,忆起当年他做沙门的最后一天,他心中就曾对此人产生过热爱。他感激地接受了瓦苏代瓦的邀请。靠岸后,他帮船夫把小船在木桩上系好。然后,船夫请他走进茅屋,给他端来面包和水,席特哈尔塔吃得津津有味,而且还吃了瓦苏代瓦款待他的水果。

后来,日落时分,他们俩坐在岸边一棵树的树干上,席特哈尔塔给船夫讲自己的出身和生活,那些绝望时刻的情景就像今天一样历历在目。他一直讲到夜深。

瓦苏代瓦全神贯注地听着。他仔细地倾听一切,出身和童年,所有的学习,所有的探索,所有的欢乐,所有的痛苦。善于倾听正是瓦苏代瓦的重要美德之一,能像他这样倾听的人不多。他并没有说一句话,讲述者就感觉到他把话全都听进去了。他安静、坦诚和期待地听着,一字不漏,没有丝毫的不耐烦,也不作褒贬,只是倾听。席特哈尔塔感到,能向这样一位倾听者诉说自己的生活、自己的探索和自己的烦恼,实在是一件幸事。

当席特哈尔塔快讲到结尾时,他讲到河边那棵树,讲到自己的潦倒落魄,讲到那神圣的“唵”,以及他如何在睡了一觉之后对河水深感热爱。这时,船夫听得更是加倍专心了,他全神贯注地闭着眼睛听。

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

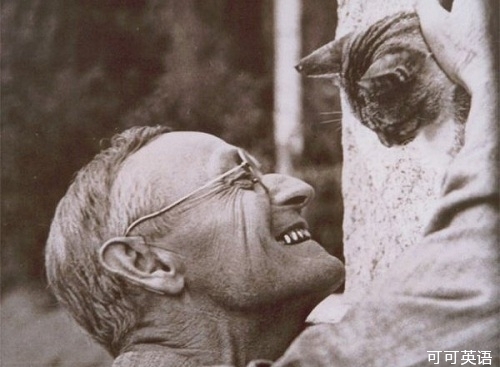

作者简介:

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

主要生平及创作

出生于德国西南部的小城卡尔夫的一个牧师家庭。自幼在浓重的宗教气氛中长大,1891年,他通过“邦试”,考入毛尔布隆神学校。由于不堪忍受经院教育的摧残,半年后逃离学校。这期间他游历许多城市,从事过多种职业。

在比较广泛地接受东西方文化熏陶之后,1904年,黑塞发表了长篇小说《彼得·卡门青特》,一举成名,从此成为专业作家。这一年他与玛丽结婚,移居巴登湖畔,埋头写作,1906年发表了长篇小说《在轮下》。这一时期的创作以浪漫主义诗歌、田园诗风格的抒情小说和流浪汉小说为主,作品洋溢着对童年和乡土的思念之情,充满对广大自然和人类的爱,同时也表现了青年人的精神苦闷与追求。

第一次世界大战后,黑塞的创作发生了明显的变化,他醉心于尼采哲学,求助于印度佛教和中国的老庄哲学,并对荣格的精神分析产生了深厚的兴趣。他试图从宗教、哲学和心理学方面探索人类精神解放的途径。这时期的长篇小说有《克努尔普》(1916)、《德米安》(1919)、《席特哈尔塔》(1922)、《荒原狼》(1927)和《纳尔齐斯与歌尔德蒙》(1930)等。这些书深受西方读者的喜爱,得到极高的评价,其中《荒原狼》曾轰动欧美,被托马斯·曼誉为德国的《尤利西斯》。

30年代后,法西斯在德国猖獗,黑塞对社会前途陷入深深的怀疑与绝望之中,但他仍不倦地从东西方宗教与哲学中寻求理想世界,《东方之行》(1932)、《玻璃球游戏》(1943)正是这一时期追求与探索的结晶。

黑塞被雨果·巴尔称为德国浪漫派最后一位骑士,这说明他在艺术上深受浪漫主义诗歌的影响。他热爱大自然,厌倦都市文明,作品多采用象征手法,文笔优美细腻;由于受精神分析影响,他的作品着重在精神领域里进行挖掘探索,无畏而诚实地剖析内心,因此他的小说具有心理的深度。1946年,"由于他的富于灵感的作品具有遒劲的气势和洞察力,也为崇高的人道主义理想和高尚风格提供一个范例",黑塞获诺贝尔文学奖。