(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

"You have come," said Siddhartha and smiled.

"I have come," said Govinda.

WITH THE SAMANAS

In the evening of this day they caught up with the ascetics, the skinny Samanas, and offered them their companionship and--obedience. They were accepted.

Siddhartha gave his garments to a poor Brahman in the street. He wore nothing more than the loincloth and the earth-coloured, unsown cloak. He ate only once a day, and never something cooked. He fasted for fifteen days. He fasted for twenty-eight days. The flesh waned from his thighs and cheeks. Feverish dreams flickered from his enlarged eyes, long nails grew slowly on his parched fingers and a dry, shaggy beard grew on his chin. His glance turned to icy when he encountered women; his mouth twitched with contempt, when he walked through a city of nicely dressed people. He saw merchants trading, princes hunting, mourners wailing for their dead, whores offering themselves, physicians trying to help the sick, priests determining the most suitable day for seeding, lovers loving, mothers nursing their children--and all of this was not worthy of one look from his eye, it all lied, it all stank, it all stank of lies, it all pretended to be meaningful and joyful and beautiful, and it all was just concealed putrefaction. The world tasted bitter. Life was torture.

A goal stood before Siddhartha, a single goal: to become empty, empty of thirst, empty of wishing, empty of dreams, empty of joy and sorrow. Dead to himself, not to be a self any more, to find tranquility with an emptied heard, to be open to miracles in unselfish thoughts, that was his goal. Once all of my self was overcome and had died, once every desire and every urge was silent in the heart, then the ultimate part of me had to awake, the innermost of my being, which is no longer my self, the great secret.

Silently, Siddhartha exposed himself to burning rays of the sun directly above, glowing with pain, glowing with thirst, and stood there, until he neither felt any pain nor thirst any more. Silently, he stood there in the rainy season, from his hair the water was dripping over freezing shoulders, over freezing hips and legs, and the penitent stood there, until he could not feel the cold in his shoulders and legs any more, until they were silent, until they were quiet. Silently, he cowered in the thorny bushes, blood dripped from the burning skin, from festering wounds dripped pus, and Siddhartha stayed rigidly, stayed motionless, until no blood flowed any more, until nothing stung any more, until nothing burned any more.

Siddhartha sat upright and learned to breathe sparingly, learned to get along with only few breathes, learned to stop breathing. He learned, beginning with the breath, to calm the beat of his heart, leaned to reduce the beats of his heart, until they were only a few and almost none.

Instructed by the oldest if the Samanas, Siddhartha practised self-denial, practised meditation, according to a new Samana rules. A heron flew over the bamboo forest--and Siddhartha accepted the heron into his soul, flew over forest and mountains, was a heron, ate fish, felt the pangs of a heron's hunger, spoke the heron's croak, died a heron's death. A dead jackal was lying on the sandy bank, and Siddhartha's soul slipped inside the body, was the dead jackal, lay on the banks, got bloated, stank, decayed, was dismembered by hyaenas, was skinned by vultures, turned into a skeleton, turned to dust, was blown across the fields. And Siddhartha's soul returned, had died, had decayed, was scattered as dust, had tasted the gloomy intoxication of the cycle, awaited in new thirst like a hunter in the gap, where he could escape from the cycle, where the end of the causes, where an eternity without suffering began. He killed his senses, he killed his memory, he slipped out of his self into thousands of other forms, was an animal, was carrion, was stone, was wood, was water, and awoke every time to find his old self again, sun shone or moon, was his self again, turned round in the cycle, felt thirst, overcame the thirst, felt new thirst.

Siddhartha learned a lot when he was with the Samanas, many ways leading away from the self he learned to go. He went the way of self-denial by means of pain, through voluntarily suffering and overcoming pain, hunger, thirst, tiredness. He went the way of self-denial by means of meditation, through imagining the mind to be void of all conceptions. These and other ways he learned to go, a thousand times he left his self, for hours and days he remained in the non-self. But though the ways led away from the self, their end nevertheless always led back to the self. Though Siddhartha fled from the self a thousand times, stayed in nothingness, stayed in the animal, in the stone, the return was inevitable, inescapable was the hour, when he found himself back in the sunshine or in the moonlight, in the shade or in the rain, and was once again his self and Siddhartha, and again felt the agony of the cycle which had been forced upon him.

“你来了。”席特哈尔塔说,微微一笑。

“我来了。”戈文达说。

和沙门在一起

这天晚上,他们追上了那几个苦行僧,那几个枯瘦的沙门,表示愿意跟他们同行并服从他们,因而被接纳了。

席特哈尔塔把自己的衣服送给了街上的一个穷婆罗门。他只系一条遮羞带,身披没有缝过的土色斗篷。他每天只吃一餐,而且从来不吃煮过的食物。他斋戒了十五天。他斋戒了二十八天。他腿上和脸上的肉都逐渐消失了。热烈的梦想在他那显然变大的眼睛里闪烁,枯瘦的手指上长出了长长的指甲,下巴上也长出了干枯、蓬乱的胡子。他遇见女人时目光变得冷冰冰,穿过城市碰到穿戴华丽的人时就轻蔑地撇撇嘴。他看见商贩做买卖,贵族外出打猎,服丧者为死人哀哭,妓女卖弄色相,医生诊治病人,僧侣择定播种的日子,变人相亲相爱,母亲给孩子喂奶——然而,他对这一切又不屑一顾,一切都是欺骗,一切都是臭哄哄的,一切都散发着谎言的恶臭,一切都伪装成高雅、幸福和美好的样子,一切都在腐烂变质。世界的味道真苦涩,生活就是烦恼。

席特哈尔塔眼前有一个目标,一个唯一的目标,那就是万事皆空,没有渴求,没有愿望,没有梦想,也没有苦和乐。自动消亡,不再有自我,为变空的心觅得安宁,在舍弃自我的思索中等着奇迹出现,这就是他的目标。如果整个自我都被克服了消亡了,如果心中的欲望和本能都已沉寂,那么,最后的东西,那个不再是自我的内在本性,那个大秘密,就会觉醒。

席特哈尔塔默默地站在直射的烈日下,疼痛得厉害,干渴得厉害,一直站到他不再感觉到疼痛和干渴。雨季里,他默默地站在雨中,水珠从他的头发滴落到冰冷的肩膀上,滴落到冰冷的腰上和腿上,这个忏悔者却站着不动,直到双肩和两腿都不再感觉到冷,直到它们麻木,直到它们平静下来。他默默地蹲在荆棘丛中,灼痛的皮肤淌出了血,溃烂的伤口流出了脓,席特哈尔塔木然地蹲着,一动不动地蹲着,直到不再出血,直到不再针扎般疼痛,直到不再烧灼般疼痛。

席特哈尔塔挺直地坐着,学习节省呼吸,学习稍加呼吸即可,学习屏住呼吸。他由呼吸开始,进而学习平定心跳,学习减少心跳的次数,一直到很少甚至几乎没有了心路。

席特哈尔塔受年纪最老的那个沙门指教,练习摆脱自我,练习专心潜修,按照新的沙门规矩来苦练。一只鹭鸟飞过竹林——席特哈尔塔让灵魂钻入了鹭鸟,飞越森林和山脉。他变成了鹭鸟,吞吃鲜鱼,像鹭鸟那样挨饿,发出鹭鸟的啼叫声,像鹭鸟那样死去。一只死狼躺在沙岸上。席特哈尔塔的灵魂钻进了那具尸体,变成了死狼,躺在沙滩上,膨胀,发臭,腐烂,被鬣狗撕碎,被兀鹰啄食,变成了骨架,化作尘土,吹散到原野里。席特哈尔塔的灵魂又回来了,经过了死亡、腐烂和尘化,已经堂到了轮回的可怕滋味,在新的渴望中就像一个猎手那样期待着冲出缺口,以逃脱这种轮回,一直找到起因的尽头,从而开始无痛苦的永恒。他破坏了自己的知觉,破坏了自己的记忆,从自我变成成千上万种陌生的形象,变成了动物、腐尸、石头、木头和水,但每次又总是重新醒来,太阳或者月亮当空,他重新变成自我,在这种徨中摇摆晃动,感到干渴,克服干渴,又感到新的干渴。

席特哈尔塔从沙门那儿学到了很多东西,他学会了从自我出发走许多条路。他经历了痛苦,经历了自愿受的痛苦,克服了痛苦、饥渴与困乏。他通过冥思苦想,通过对各种想法的含义进行空想,走上了摆脱自我之路炝 学会了走这些路以及别的路,千百次地摆脱他的自我,在非我中逗留几个钟头乃至几天。可是,尽管这些路都是从自我出发的,其终点却又总是回到自我。虽然席特哈尔塔千百次地逃离自我,在虚无中留连,在动物、石头中留连,回归却是无可避免的,重新寻获自己的时刻是逃脱不了的,不论是在阳光下还晨月光下,不论是在树荫里还是在雨中,他重又变成了自我和席特哈尔塔,重又感觉到承受轮回的痛苦。

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

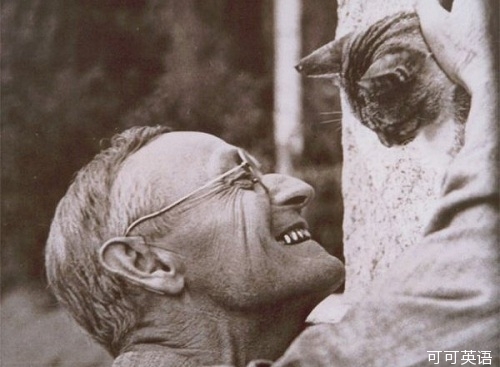

作者简介:

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

主要生平及创作

出生于德国西南部的小城卡尔夫的一个牧师家庭。自幼在浓重的宗教气氛中长大,1891年,他通过“邦试”,考入毛尔布隆神学校。由于不堪忍受经院教育的摧残,半年后逃离学校。这期间他游历许多城市,从事过多种职业。

在比较广泛地接受东西方文化熏陶之后,1904年,黑塞发表了长篇小说《彼得·卡门青特》,一举成名,从此成为专业作家。这一年他与玛丽结婚,移居巴登湖畔,埋头写作,1906年发表了长篇小说《在轮下》。这一时期的创作以浪漫主义诗歌、田园诗风格的抒情小说和流浪汉小说为主,作品洋溢着对童年和乡土的思念之情,充满对广大自然和人类的爱,同时也表现了青年人的精神苦闷与追求。

第一次世界大战后,黑塞的创作发生了明显的变化,他醉心于尼采哲学,求助于印度佛教和中国的老庄哲学,并对荣格的精神分析产生了深厚的兴趣。他试图从宗教、哲学和心理学方面探索人类精神解放的途径。这时期的长篇小说有《克努尔普》(1916)、《德米安》(1919)、《席特哈尔塔》(1922)、《荒原狼》(1927)和《纳尔齐斯与歌尔德蒙》(1930)等。这些书深受西方读者的喜爱,得到极高的评价,其中《荒原狼》曾轰动欧美,被托马斯·曼誉为德国的《尤利西斯》。

30年代后,法西斯在德国猖獗,黑塞对社会前途陷入深深的怀疑与绝望之中,但他仍不倦地从东西方宗教与哲学中寻求理想世界,《东方之行》(1932)、《玻璃球游戏》(1943)正是这一时期追求与探索的结晶。

黑塞被雨果·巴尔称为德国浪漫派最后一位骑士,这说明他在艺术上深受浪漫主义诗歌的影响。他热爱大自然,厌倦都市文明,作品多采用象征手法,文笔优美细腻;由于受精神分析影响,他的作品着重在精神领域里进行挖掘探索,无畏而诚实地剖析内心,因此他的小说具有心理的深度。1946年,"由于他的富于灵感的作品具有遒劲的气势和洞察力,也为崇高的人道主义理想和高尚风格提供一个范例",黑塞获诺贝尔文学奖。