(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

Siddhartha had started to nurse discontent in himself, he had started to feel that the love of his father and the love of his mother, and also the love of his friend, Govinda, would not bring him joy for ever and ever, would not nurse him, feed him, satisfy him. He had started to suspect that his venerable father and his other teachers, that the wise Brahmans had already revealed to him the most and best of their wisdom, that they had already filled his expecting vessel with their richness, and the vessel was not full, the spirit was not content, the soul was not calm, the heart was not satisfied. The ablutions were good, but they were water, they did not wash off the sin, they did not heal the spirit's thirst, they did not relieve the fear in his heart. The sacrifices and the invocation of the gods were excellent--but was that all? Did the sacrifices give a happy fortune? And what about the gods? Was it really Prajapati who had created the world? Was it not the Atman, He, the only one, the singular one? Were the gods not creations, created like me and you, subject to time, mortal? Was it therefore good, was it right, was it meaningful and the highest occupation to make offerings to the gods? For whom else were offerings to be made, who else was to be worshipped but Him, the only one, the Atman? And where was Atman to be found, where did He reside, where did his eternal heart beat, where else but in one's own self, in its innermost part, in its indestructible part, which everyone had in himself? But where, where was this self, this innermost part, this ultimate part? It was not flesh and bone, it was neither thought nor consciousness, thus the wisest ones taught. So, where, where was it? To reach this place, the self, myself, the Atman, there was another way, which was worthwhile looking for? Alas, and nobody showed this way, nobody knew it, not the father, and not the teachers and wise men, not the holy sacrificial songs! They knew everything, the Brahmans and their holy books, they knew everything, they had taken care of everything and of more than everything, the creation of the world, the origin of speech, of food, of inhaling, of exhaling, the arrangement of the senses, the acts of the gods, they knew infinitely much--but was it valuable to know all of this, not knowing that one and only thing, the most important thing, the solely important thing?

Surely, many verses of the holy books, particularly in the Upanishades of Samaveda, spoke of this innermost and ultimate thing, wonderful verses. "Your soul is the whole world", was written there, and it was written that man in his sleep, in his deep sleep, would meet with his innermost part and would reside in the Atman. Marvellous wisdom was in these verses, all knowledge of the wisest ones had been collected here in magic words, pure as honey collected by bees. No, not to be looked down upon was the tremendous amount of enlightenment which lay here collected and preserved by innumerable generations of wise Brahmans.-- But where were the Brahmans, where the priests, where the wise men or penitents, who had succeeded in not just knowing this deepest of all knowledge but also to live it? Where was the knowledgeable one who wove his spell to bring his familiarity with the Atman out of the sleep into the state of being awake, into the life, into every step of the way, into word and deed? Siddhartha knew many venerable Brahmans, chiefly his father, the pure one, the scholar, the most venerable one. His father was to be admired, quiet and noble were his manners, pure his life, wise his words, delicate and noble thoughts lived behind its brow --but even he, who knew so much, did he live in blissfulness, did he have peace, was he not also just a searching man, a thirsty man? Did he not, again and again, have to drink from holy sources, as a thirsty man, from the offerings, from the books, from the disputes of the Brahmans? Why did he, the irreproachable one, have to wash off sins every day, strive for a cleansing every day, over and over every day? Was not Atman in him, did not the pristine source spring from his heart? It had to be found, the pristine source in one's own self, it had to be possessed! Everything else was searching, was a detour, was getting lost.

Thus were Siddhartha's thoughts, this was his thirst, this was his suffering.

Often he spoke to himself from a Chandogya-Upanishad the words: "Truly, the name of the Brahman is satyam--verily, he who knows such a thing, will enter the heavenly world every day." Often, it seemed near, the heavenly world, but never he had reached it completely, never he had quenched the ultimate thirst. And among all the wise and wisest men, he knew and whose instructions he had received, among all of them there was no one, who had reached it completely, the heavenly world, who had quenched it completely, the eternal thirst.

"Govinda," Siddhartha spoke to his friend, "Govinda, my dear, come with me under the Banyan tree, let's practise meditation."

They went to the Banyan tree, they sat down, Siddhartha right here, Govinda twenty paces away. While putting himself down, ready to speak the Om, Siddhartha repeated murmuring the verse:

Om is the bow, the arrow is soul, The Brahman is the arrow's target, That one should incessantly hit.

After the usual time of the exercise in meditation had passed, Govinda rose. The evening had come, it was time to perform the evening's ablution. He called Siddhartha's name. Siddhartha did not answer. Siddhartha sat there lost in thought, his eyes were rigidly focused towards a very distant target, the tip of his tongue was protruding a little between the teeth, he seemed not to breathe. Thus sat he, wrapped up in contemplation, thinking Om, his soul sent after the Brahman as an arrow.

Once, Samanas had travelled through Siddhartha's town, ascetics on a pilgrimage, three skinny, withered men, neither old nor young, with dusty and bloody shoulders, almost naked, scorched by the sun, surrounded by loneliness, strangers and enemies to the world, strangers and lank jackals in the realm of humans. Behind them blew a hot scent of quiet passion, of destructive service, of merciless self-denial.

In the evening, after the hour of contemplation, Siddhartha spoke to Govinda: "Early tomorrow morning, my friend, Siddhartha will go to the Samanas. He will become a Samana."

席特哈尔塔心中的不满足开始增加。他开始感到,父亲的爱,母亲的爱,以及好友戈文达的爱,并不能永远使他幸福,使他平静,使他知足,使他心满意足。他开始担心,他的可敬的父亲以及别的老师,那些聪明的婆罗门,已经把智慧的精华传给了他,把他们的丰富知识注入了他那期待的容器,而这个容器却没能盛满,精神没能满足,灵魂没能安宁,心也没能平静下来。洗礼虽好,但它们是水,洗不掉罪孽,治不好精神的焦渴,解除不了内心的恐惧。对神灵的祭祀和祈求当然很好——可是,这就是一切了吗?祭祀可曾带来了幸福?而神灵的作品又怎么样呢?真的是生主创造了世界?难道不是阿特曼,这个独一无二的万物之主?神灵们又何尝不像你我一样是被创造出来的形象,受制于时间,是暂时而非永恒的?祭祀神灵果真是好事,果真对头,是合情合理和至高无上的行动?除了独一无二的阿特曼,还有谁值得祭祀,还有谁值得崇拜?到哪儿才能找到阿特曼,他住在何处,他那永恒的心在何处跳动?除了在自我之中,在内心深处,在每个人内心的坚不可摧之中,还会在何处?而这个自我,这个内心深处,这个最后的东西,又在何处?它不是肉和腿,不是思想也不是意识,那些圣贤就是这么教导的。那么,它在哪儿,到底在哪儿呢?要挤到那儿去,渗入自我,渗入我心中,渗入阿特曼——但是否还有另一条路值得去探索呢?啊,没有人指出这条路,没有人知道它,父亲不知道,老师和贤人不知道,那些神圣的祭祀歌也不知道!而波罗门以及他们的神圣经书却知道一切。他们知道一切,关心一切,甚至超出了一切,世界的创造,言语、饮食和呼吸的产生,感觉和呼吸的产生,感觉的秩序,神灵们的业绩——他们知道无限多的东西——但是,如果不知道这独一无二的东西,这最最重要的东西,这唯一重要的东西,知道那一切又有什么价值呢?

确实,在神圣经书中的许多诗,尤其是在《娑摩吠陀》的《奥义书》里,都讲到了这种最内在、最终的东西,真是了不起的诗。“你的灵魂就是整个世界。”里面这样写道,还写着人在睡觉时,在酣睡中,便进入自己内心深处,到了阿特曼之中。在这些诗里显示了惊人的智慧,最聪明的人的所有知识都集中在这里,体现为具有魔力的语句,纯净得就像蜜蜂采到的蜜。不,千万别小看这巨大的知识财富,它们被数不清的一代代聪明的婆罗门搜集和保存在这里。——可是,那些不仅了解而且体验了这种最深刻知识的人,那些婆罗门,那些僧侣,那些贤人或忏悔者,究竟在哪儿?而能够把沉湎于阿特曼之中的人从酣睡中唤醒,使之清醒,进入生活,迈步前行,说话做事的内行人又在何处?席特哈尔塔认识许多可敬的婆罗门,首先是他的父亲,那个高尚的人,那个学者,那个值得敬重的人。他父亲令人敬佩,举止安详和高贵,生活纯朴,言语聪明,头脑里有机智和高尚的思想 但即便是他,有那么多知识,就算是生活在幸福之中,拥有平静安宁了吗?难道它不也是一个探索者、渴求者吗?难道他不也是一个焦渴的人,不得不再三地跑到圣泉边痛饮,从祭祀中,从书籍中,从婆罗门的交谈中汲取养分吗?他这个无可非议的人,为什么每天都得洗涤罪孽,每天都要努力洗涤,每天都要重新努力呢?难道阿特曼不在他身上,难道根本不源不在他心里流淌?必须找到它,这个自我之中的根本之源,必须拥有它!而别的一切都是探索,都是走弯路,都是误入歧途。

席特哈尔塔的想法就是这样,这是他的渴望,这是他的苦恼。

他经常朗读一篇《奥义书》里的话:“确实,婆罗门这个名称就是真理——真的,谁明白了这点,就能天天进入天上的世界。”那天上的世界往往已经临近,可是他却从来没完全达到,从来没消除过最后的焦渴。所有圣贤,凡是他认识并受到教诲的,没有一个完全到达了那天上的世界,完全消除了永恒的焦渴。

“戈文达,”席特哈尔塔对他的朋友说,“戈文达,亲爱的,跟我一起到榕树下面去吧,咱们该专心潜修了。”

他们走到榕树那儿,坐下来,这边是席特哈尔塔,离他二十步远是戈文达。席特哈尔塔坐下,做好了念经的准备,接着便喃喃地反复念起来:

口奄是弓,心灵是箭,婆罗门便是箭之靶,应当始终不渝射向它。

在正常的沉思潜修的时间过去之后,戈文达站了起来。傍晚降临了,到晚间沐浴的时候了。他呼唤席特哈尔塔的名字,席特哈尔塔却没回答。席特哈尔塔仍在沉思打坐,眼睛呆呆地凝视着一个远远的目标,舌尖稍稍从牙齿间伸出,似乎没有了呼吸。他就这样坐着,沉浸在专注之中,默默念诵着“口奄”,心灵已作为箭射向婆罗门。

那时,有几个沙门经过席特哈尔塔所在的城市。他们是去朝圣的苦行僧,三个瘦削、憔悴的汉子,既不年老也不年轻,风尘仆仆,肩上出血,几乎光着身子,被太阳晒得焦黑,生活在孤独之中,对尘世既生疏又敌对,称是人世间的陌生人和瘦狼。从他们身后飘过来一股强烈的气味,那是充满了平静的激情、坚忍的修行和无情的抑制的自我的气味。

晚上,在沉思潜修的功课之后,席特哈尔塔对戈文达说:“明天清早,朋友,席特哈尔塔要去找沙门,他要当一个沙门。”

背景阅读

本书简介:

古印度贵族青年悉达多英俊聪慧,拥有人们羡慕的一切。为了追求心灵的安宁,他孤身一人展开了求道之旅。他在舍卫城聆听佛陀乔答摩宣讲教义,在繁华的大城中结识了名妓伽摩拉,并成为一名富商。心灵与肉体的享受达到顶峰,却让他对自己厌倦、鄙弃到极点。在与伽摩拉最后一次欢爱之后,他抛弃了自己所有世俗的一切,来到那河边,想结束自己的生命。在那最绝望的一刹那,他突然听到了生命之河永恒的声音……经过几乎一生的追求,悉达多终于体验到万事万物的圆融统一,所有生命的不可摧毁的本性,并最终将自我融入了瞬间的永恒之中。

作者简介:

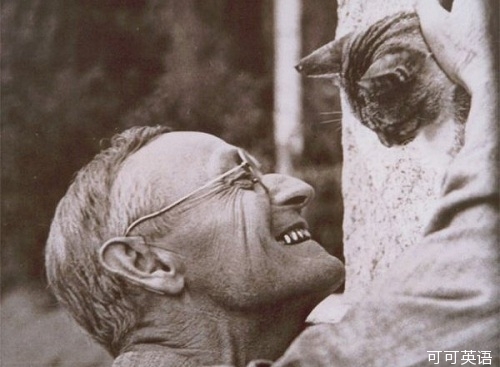

赫尔曼·黑塞(Hermann Hesse,1877.7.2-1962.8.9)德国作家。1923年46岁入瑞士籍。1946年获诺贝尔文学奖。1962年于瑞士家中去世。爱好音乐与绘画,是一位漂泊、孤独、隐逸的诗人。黑塞的诗有很多充满了浪漫气息,从他的最初诗集《浪漫之歌》的书名,也可以看出他深受德国浪漫主义诗人的影响,以致后来被人称为“德国浪漫派最后的一个骑士”。主要作品有《彼得·卡门青》、《荒原狼》、《东方之行》、《玻璃球游戏》等。

主要生平及创作

出生于德国西南部的小城卡尔夫的一个牧师家庭。自幼在浓重的宗教气氛中长大,1891年,他通过“邦试”,考入毛尔布隆神学校。由于不堪忍受经院教育的摧残,半年后逃离学校。这期间他游历许多城市,从事过多种职业。

在比较广泛地接受东西方文化熏陶之后,1904年,黑塞发表了长篇小说《彼得·卡门青特》,一举成名,从此成为专业作家。这一年他与玛丽结婚,移居巴登湖畔,埋头写作,1906年发表了长篇小说《在轮下》。这一时期的创作以浪漫主义诗歌、田园诗风格的抒情小说和流浪汉小说为主,作品洋溢着对童年和乡土的思念之情,充满对广大自然和人类的爱,同时也表现了青年人的精神苦闷与追求。

第一次世界大战后,黑塞的创作发生了明显的变化,他醉心于尼采哲学,求助于印度佛教和中国的老庄哲学,并对荣格的精神分析产生了深厚的兴趣。他试图从宗教、哲学和心理学方面探索人类精神解放的途径。这时期的长篇小说有《克努尔普》(1916)、《德米安》(1919)、《席特哈尔塔》(1922)、《荒原狼》(1927)和《纳尔齐斯与歌尔德蒙》(1930)等。这些书深受西方读者的喜爱,得到极高的评价,其中《荒原狼》曾轰动欧美,被托马斯·曼誉为德国的《尤利西斯》。

30年代后,法西斯在德国猖獗,黑塞对社会前途陷入深深的怀疑与绝望之中,但他仍不倦地从东西方宗教与哲学中寻求理想世界,《东方之行》(1932)、《玻璃球游戏》(1943)正是这一时期追求与探索的结晶。

黑塞被雨果·巴尔称为德国浪漫派最后一位骑士,这说明他在艺术上深受浪漫主义诗歌的影响。他热爱大自然,厌倦都市文明,作品多采用象征手法,文笔优美细腻;由于受精神分析影响,他的作品着重在精神领域里进行挖掘探索,无畏而诚实地剖析内心,因此他的小说具有心理的深度。1946年,"由于他的富于灵感的作品具有遒劲的气势和洞察力,也为崇高的人道主义理想和高尚风格提供一个范例",黑塞获诺贝尔文学奖。