(单词翻译:单击)

Part one

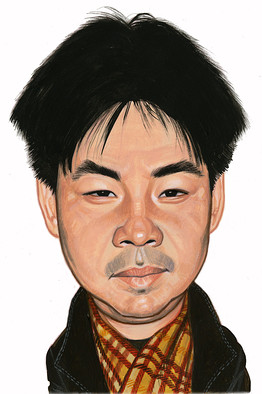

Walking through the capital's university district, Yu Hua looks more like a migrant worker than one of China's best-selling authors. His hair short and spiky, his clothes simple and plain, he does not fit in -- and clearly doesn't make much of an effort to do so.

余华走在北京的大学区里,看上去更像是一个农民工,而不像是中国一流的畅销书作家。他短短的头发直竖起来,衣服简单而朴素,而且不大合身──很显然,他也没在这方面下什么功夫。

That attitude extends to his view of contemporary society, which he says is so sick that a writer can't pretend to be a doctor. Instead, the best one can do is admit that one is ill and try to describe the symptoms. This ethos underpins 'Brothers,' a sprawling, two-part novel that has just come out in an English translation in the U.S. and will be published in April in Britain.

这种态度延伸到了他对当代社会的看法。他说,这个社会已经无药可救,作家也不能再扮作社会的医生。一个人所能做的就是承认自己有病,并且尽力去描述病情。这一思想贯穿着《兄弟》,一部分为上下两部的长篇巨制。这部小说的英文版刚刚在美国问世,今年四月该书还将在英国上市。

The book is a manic, hyperactive account of two brothers whose stories span the past 50 years of hardcore communism and today's no-holds-barred capitalism. 'At times the novel is grotesque and crude, but there's nothing I write about that is more absurd than what goes on in society,' he says as we rush past crowds of university students en route to a restaurant that serves the cuisine of Mr. Yu's native Zhejiang province.

余华以一种疯狂而亢奋的笔触叙述了两兄弟的故事。整个小说从过去纯粹的共产主义写到今天不折不扣的资本主义,横跨了五十年。余华在我们匆匆穿过一群群大学生,去往一家经营浙江菜的餐厅途中说,这部小说有时候显得怪诞而粗俗,但社会上真实发生的事情比我笔下所有的故事更为荒诞不经。浙江是余华的老家。

Politics is one of the 46-year-old's main interests. His most famous work, 'To Live,' is a brutal, mythic tale of a man who loses all to the political movements that tore across China during the first three decades of Communist Party rule, but manages to keep going through his sheer will to live. The book, which was filmed by the star director Zhang Yimou, remains a bestseller in China. His other works are symbolic almost to the point of caricature. His 1995 'Chronicles of a Blood Merchant' tells the story of a man who sells his blood to get by. 'Cries in the Drizzle,' published in 2003, is about a boy who seems to bring bad luck to everyone he touches.

政治是46岁的余华最感兴趣的领域之一。他最知名的作品《活着》讲述的是一个虚构的残忍故事。在共产党执政的头三十年里,故事的主人公在席卷中国的政治运动中失去了自己的所有,但他凭着活下去的决心生存了下来。这部小说至今在中国还是本畅销书,这个故事还被著名导演张艺谋搬上了大荧幕。他的其他作品很有象征意味,简直和漫画有异曲同工之妙。他1995年的小说《许三观卖血记》讲述了一个男人为维持生计而卖血的故事。2003年出版的《在细雨中呼喊》是关于一个男孩的故事。这个男孩碰谁一下,谁似乎就会倒霉。

'Brothers' is strongly in that vein. It follows two half-brothers whose lives are almost a parody of reform-era China: one a crass, vulgar businessman who succeeds through corruption and brutality, and fetishizes virgins; the other a meek man who ends up victimized by higher economic forces. When it came out in 2005 and 2006, it elicited protests from literary critics across the country, who said the novel makes heroes of villains and descends to the level of fart jokes for humor. There was even a collection of essays published by a group of critics called 'Pulling Yu Hua's Teeth,' a play on his first profession of dentistry.

《兄弟》延续了这样的风格。小说中那对异父异母兄弟的生活简直就是对改革时期中国戏剧式的再现:弟弟是个粗鲁、邋遢的生意人,靠着钻空子和一股子狠劲儿发家,内心还有处女情结;老实的哥哥则最终成为经济大转型时代的牺牲品。这本小说的上下两部分别在2005年和2006年问世后,遭到了全国上下文学批评家们的反对声浪。他们认为,这部小说把无赖歌颂成英雄,而且为了搏人一笑小说沦落到了粗俗的地步。一些文学批评家甚至还出版了一本名为《给余华拔牙》的评论集,嘲弄余华的第一份职业是牙医。

Mr. Yu shrugs off the disapproval. Most of his critics, he says, are young people who are either ashamed he's airing China's dirty linen, or don't even realize that the corrupt backwaters he describes still exist in modern China. 'This generation that grew up in the 1980s only experienced a China that was getting better and better,' he says. 'They thought their lives represented all of China. But this is a mistake. China has over 100 million people earning less than 800 yuan ($125) a year.'

余华对这些批评并不在意。他说,大多数批评他的人是年轻人,他们或者不喜欢看到他揭露中国黑暗的一面,或者根本没有意识到他在书中描写的那些阴暗面依然存在于现代的中国。他说,80后的这一代人只感受到了一个越变越好的中国。他们认为全中国人都过着和他们一样的生活。但那是错误的。中国有超过1亿人的年收入不足人民币800元(合125美元)。

Part two

Mr. Yu is concerned that his critics are no more independent thinkers than their counterparts in the Cultural Revolution, which ran from 1966 to 1976 -- while Mr. Yu was growing up. In those days, China turned into a totalitarian madhouse focused on the personality cult of leader Mao Zedong. Now, over the past three decades, China has embraced capitalism with the same level of fervor. 'China has these huge bubbles,' he says. 'The Cultural Revolution was the world's biggest revolutionary bubble and now we have the world's biggest capitalist bubble.'

余华担心,这些年轻人和文革时的那些年轻人一样,也缺少独立思考的能力。余华正是成长在1966年至1976年的文革时期。那时候,中国的极权统治登峰造极,对毛泽东大搞个人崇拜。而在过去的这三十年里,中国以同样的热情拥抱了资本主义。余华说,中国有这些巨大的泡沫,文化大革命是世界上最大的革命泡沫,而现在我们有世界上最大的资本主义泡沫。

The problem with writing about today's China, he says, is that change is so rapid it's almost impossible to do it justice. 'China's changes are like hundreds of years of European history compressed together,' he says 'The Cultural Revolution was like our dark ages. Now we're in the 21st century, just like the West. From one era to the other, it's almost too fast.'

他说,描写当代中国的困难在于,中国的变化太快了,人们难以做出公正的评判。中国的变化就好像是把欧洲几百年的历史浓缩到了一起,文化大革命就像是我们的黑暗时代。现在我们和西方一样进入了21世纪。我们从一个时代跳到了另一个时代,变化太快了。

Western critics have been surprised that 'Brothers' was not banned. But Mr. Yu notes that pointing out the country's impoverished countryside or corruption are themes that the state-run press harps on daily. Mr. Yu thinks that some of the West's surprise at the topics in 'Brothers' is because so much of contemporary Chinese fiction sold in the West is written by exiles. That's led to an assumption that current-day topics are out of bounds.

西方的批评家一直对《兄弟》未遭禁感到惊讶。余华表示,指出中国农村的贫困和腐败问题也是官方媒体每天喋喋不休的话题。余华认为,一些西方人之所以对《兄弟》一书的主题感到奇怪,是因为在西方,很多关于当代中国的小说都是流亡海外的作家创作的。这就促使人们认为当代的主题都是不可触碰的禁区。

Whether this is true or not, it is remarkable how much Chinese living abroad have shaped Westerners' perceptions of China. Indeed, almost all Chinese authors who are famous in the West also live in the West, among them: Gao Xingjian (2000 Nobel Prize for Literature), Ha Jin (1999 National Book Award), Ma Jian, Li Yiyun and Dai Sijie. Most deal with China in the 1960s, '70s or '80s.

不论这是不是事实,居住在海外的中国人都在十分明显地影响着西方人对中国的看法。事实上,几乎所有在西方知名的中国作家都生活在西方,其中包括:高行健(2000年诺贝尔文学奖得主)、哈金(1999年美国国家图书奖得主)、马建、李翊云和戴思杰。他们中的大多数描写的都是60、70或80年代的中国。

'I think it's hard for them to write about China nowadays,' Mr. Yu says carefully. He doesn't believe in bashing exiled writers for pandering to Western tastes -- an accusation that some have made about him as well. But he does feel almost left alone; only the author Mo Yan has a serious body of work published in the West. 'Western critics don't realize something: The most critical authors are in China, not overseas. Look, there's me, there's Mo Yan -- we criticize a lot. Anyone can criticize the Cultural Revolution nowadays. We criticize the current society.'

余华小心翼翼地说,我想,让这些作家描写当代中国有些困难。余华不想抨击流亡作家,说他们是在迎合西方趣味──有些人已经对他做出了这样的指责。但是,他的确觉得自己是只身一人。除他以外,只有作家莫言在西方出版过严肃作品。余华说,西方批评家没有意识到:最具批判眼光的作家在中国,不在海外。他说,你瞧,有我,还有莫言──我们经常批评。现在任何人都可以批评文化大革命。而我们批评当代社会。

Since Mr. Yu wrote his book, China's economy has joined the rest of the world in slowing down dramatically. That might make 'Brothers' seem like a description of a past era -- the go-go years of the early 21st century. But in other ways, China's slowdown has brought to the surface issues that Mr. Yu dealt with in 'Brothers,' such as corruption and rootlessness.

自从余华的这部小说问世以后,中国的经济增长就和其他国家一样急剧放缓。这可能会让《兄弟》看起来像是在描述一个过去的时代──21世纪初的那个奔腾年代。但是从另外的角度看,中国经济的放缓让余华在《兄弟》中描写的问题浮出了水面,比如腐败和无所寄托的状态。

But what bothers Mr. Yu more about these obvious problems is a lack of trust in society. The book trade itself is good example of this, he says. 'It's really hard for a young author to break in because there are few reputable critics. It's corrupt. People pay critics to write all sorts of nonsense.' He says reviewers charge 3,000 to 5,000 yuan for a review. The accusation is impossible to prove but it is true that China has a weak scene of literary criticism. He contrasts the situation to a western publication like France's Le Monde. He says that newspaper gave him a two-page spread, resulting in a huge spike in sales -- because French people could trust the newspaper's judgment, not as infallible but as an honest effort at reviewing a book.

然而,在这些凸显的问题中,最让余华感到困扰的是社会缺乏信任。他说,图书贸易本身就是一个很好的例子。因为几乎没有知名的文学批评家,所以年轻作家想要跻身文学圈非常困难。这就是腐败。人们花钱雇批评家写出各种毫无价值的东西。他说,批评家写一篇评论要收3,000至5,000元不等。余华的这种评论不可能得到证实,但中国的文学批评的确尽显颓象。他将这种情形和西方的出版物,比如法国的《世界报》(Le Monde)来做比较。他说,《世界报》用两个版面的篇幅为他做宣传,结果图书销量大幅增加──因为法国民众可以相信报纸上的判断,不是因为它一贯正确,而是因为它诚实地评论了这本书。

This is why, he says, literature in China is so troubled. Young talented writers have a hard time finding readers and there is almost no serious criticism to help guide readers and writers. At the heart of the issue is a dysfunctional civil society -- which takes Mr. Yu back to his favorite topic of society as a patient. 'What China lacks is public trust,' he says. 'It's what is missing the most in China right now.'

他说,这就是为什么文学在中国会面临如此多的问题。有才华的年轻作家难以找到读者,而中国几乎没有严肃的文学批评去引导读者和作家。问题的症结是一个功能紊乱的市民社会──这再次把余华带回到他喜爱的命题:一个疾病缠身的社会。他说,中国缺乏的是公众信任,这是中国当下最缺失的东西。