(单词翻译:单击)

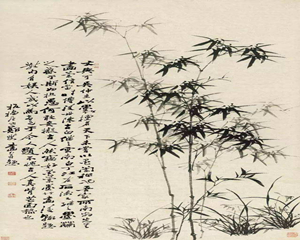

这是一首题画诗,系板桥晚年总结自己 “四十年来画竹枝” 的历程和经验,重点在第二联上,属论画性质。收在《郑板桥集·补遗·题画竹》中,原诗无题,今姑以总题为之。落款云: “乾隆戊寅十月下浣,板桥郑燮画并题。”可知作于乾隆二十三年(1758) 十月二十一日至三十日之间,时年六十六岁,六年后板桥去世。

郑燮·《板桥题画·竹》

余家有茅屋二间,南面种竹。夏日新篁初放,绿荫照人,置一小榻其中,甚凉适也。秋冬之际,取围屏骨子,断去两头,横安以为窗棂;用匀薄洁白之纸糊之。风和日暖,冻蝇触窗纸上,咚咚作小鼓声。此时一片竹影零乱,岂非天然图画乎!凡吾画竹,无所师承,多得于纸窗粉壁日光月影中耳。

江馆清秋,晨起看竹,烟光日影露气,皆浮动于疎枝密叶之间。胸中勃勃遂有画意。其实胸中有竹,并不是眼中之竹也。因而磨墨展纸,落笔倏作变相,手中之竹又不是胸中之竹也。总之,意在笔先者,定则也;趣在法外者,化机也。独画云乎哉!

余画大幅竹好画水,水与竹,性相近也。少陵云:“懒性从来水竹居”。又曰:“映竹水穿沙”。此非明证乎!渭川千亩,淇泉菉竹。西北且然,况潇湘云梦之间,洞庭青草之外,何在非水,何在非竹也!余少时读书真州之毛家桥,日在竹中闲步。潮去则湿泥软沙,潮来则溶溶漾漾,水浅沙明,绿荫澄鲜可爱。时有鲦鱼数十头,自池中溢出,游戏于竹根短草之间,与余乐也。未赋一诗,心常痒痒。今乃补之曰:风晴日午千林竹,野水穿林入林腹。绝无波浪自生纹,时有轻鲦戏相逐。月影天光暂一开,青枝碧叶还遮覆。老夫爱此饮一掬,心肺寒僵变成绿。展纸挥毫为巨幅,十丈长笺三斗墨。日短夜长继以烛,夜半如闻风声、竹声、水声秋肃肃。

Inscriptions on Painting (Bamboo)

Zheng Xie

I live in a two-room thatched house, to the south of which are bamboo groves. In the summer, the new shoots are green and succulent, and I place my couch beneath their shade to keep cool. When autumn and winter arrive, I make a window from a screen and then paste it over with thin, white paper. When the weather is fine and gentle breeze is blowing, you can hear insects drumming on it, and bamboos cast dancing shadows across it. Is that not a painting executed by Nature? I have never studied the work of others in painting bamboos but instead have learned a great deal from the shadows cast on the window paper and the walls by the sun and the moon.

Once, while lodging at a riverside hostel in early autumn, I got up in the morning to look at the bamboos and saws the mist, sunlight and shadows floating amongst their sparse branches and dense leaves. Greatly inspired, I wanted to paint them. However, the bamboos in my mind went not the same as those I had seen. After preparing my ink and laying out my paper, I lifted the brush to paint. Suddenly the bamboos had changed. They did not resemble the bamboos I pictured in my mind. Having a conception before starting to paint is a guiding principle; however, the potential for variation outside that principle is what is interesting, and this does not apply to painting alone.

When I make a large scroll of bamboos, I take great delight in the application of water, because water and bamboo are so closely related. Shaoling1 once said in a poem, “Indolent by nature, I live near water and bamboo.” He also said, “Water courses through the reflections of bamboos in the river.” Isn’t this proof enough? Around the Weichuan River is a vast expanse of paddy-fields, and around the Qiquan Lake are green bamboo. This is also true in the northwest, to say nothing of the area between the Xiaoxiang River and the Yunmeng Marshes and beyond Dongting Lake. Where there is water there must be bamboo. I studied near Mao Family Bridge in Zhenzhou and always used to take walks among the bamboos there. When the tide recede, soft, sandy land appears; when it comes in again, the lovely green reflections of bamboos can be seen in the rippling water. Sometimes dozens of little fish can be seen near the surface, darting to and fro among the bamboo roots and stubbly grasses, almost as though playing with you. I regret that I did not write a poem then. It has remained something I’ve wanted to do, so I will give way to my desire today:

Forests of bamboo bask in the noon sun and gentle breeze,

A stream roaming through their midst.

Gentle ripples disturb its still surface,

And tiny fish dart to and fro, chasing one another.

Suddenly the sun emerges,

Shining over the green branches and leaves.

I cup some water in my hands and drink,

And my benumbed heart becomes green again.

Spreading out my paper, I paint a large scroll,

Three metres long, needing three pecks of ink.

The days are short and I must continue by candlelight,

On autumn nights I hear the wind, bamboo and water

Murmuring outside.

更多精品翻译素材,敬请关注可可英语。