(单词翻译:单击)

In 1906, while studying medicine in Japan, a young Chinese man called Zhou Shuren was shown a slide depicting a scene from the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, which was partly fought on Chinese territory. It showed a crowd of Chinese watching while one of their compatriots was beheaded by the Japanese, accused of being a Russian spy. “They were all strong fellows but appeared completely apathetic,” Zhou recalled. “After this film I felt that medical science was not so important after all. The people of a weak and backward country, however strong and healthy they may be, can only serve to be made examples of, or to witness such futile spectacles. ... The most important thing, therefore, was to change their spirit, and since at that time I felt that literature was the best means to this end, I determined to promote a literary movement.”

1906年,一个名叫周树人的中国人在日本学医期间,看到一幅幻灯片,上面是1904-1905年日俄战争中的一幕,这场战争有部分是在中国的领土上发生的。幻灯片上,一个中国人被日本人认定为俄军间谍,周围的一群中国人就这样目送自己的同胞被斩首。“一样是强壮的体格,而显出麻木的神情,”周树人回忆。“从那一回以后,我便觉得学医并非一件紧要事,凡是愚弱的国民,即使体格如何强健,如何茁壮,也只能做毫无意义的示众的材料和看客……所以我们的第一要著,是在改变他们的精神,而善于改变精神的事,我那时以为当然要推文艺,于是想提倡文艺运动了。”

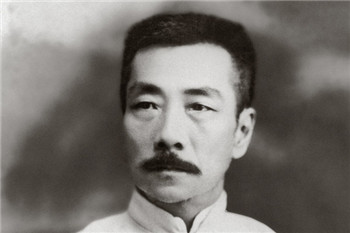

Soon after this Damascene moment — one of the most celebrated conversions in 20th-century Chinese culture — Zhou began his career as the self-appointed literary doctor of China’s spiritual ills. Across the next three decades, under the pen name Lu Xun, he became one of the founding figures of modern Chinese literature.

这个时刻是20世纪中国文学史上最著名的转变之一,不久后,周树人就自诩为文学医生,专门疗救中国人灵魂的沉疴。在接下来的30多年里,他以“鲁迅”为笔名,成了现代中国文学的奠基者之一。

Lu Xun’s publicly enunciated motives for becoming a writer have subsequently been seen as emblematic of modern Chinese literature’s obsession with politics. Like many critics before him, Yunte Huang, a professor of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara, also defines this literature as an overwhelmingly political phenomenon. It is, he explains in his introduction to this new collection of 20th-century writing from mainland China, a story that carries “the historical weight of a nation,” an expression of these writers’ crisis-ridden sense of China as a country “on the brink of .”

鲁迅公开阐明了自己成为作家的动机,后来这成为中国现代文学无法摆脱政治影响的象征。和之前的许多评论家一样,加利福尼亚大学圣塔芭芭拉分校英语系教授黄运特也把中国现代文学定义为一种过于政治化的现象。在新出版的20世纪中国大陆文学选集的导言中,他解释道,现代中国文学是一个承担着“整个民族历史重负”的故事,作家们对处在“亡国边缘”的中国表达自己的忧患意识。

There is something to be said for this reading; indeed, it dominated academic study until the early 1990s. But the equation of modern Chinese literature with politics is also something of a straitjacket. Since at least the Cold War, the stain of ideology has adversely affected its perception in the West, where nonspecialist reviewers and readers have often characterized 20th-century Chinese writing as preoccupied with didactic political messages, to the exclusion of stylistic or psychological complexity. Like literature everywhere, however, that of modern China expresses a confounding mix of history, humanism and aesthetics; it has always done far more than reflect its political context. And although this worthwhile anthology asserts the primacy of the political story, it also allows alternative literary visions to glimmer through.

然而,关于这种解读也有争议;事实上,直至20世纪90年代初,这种说法一直统治着中国的学术界。但是把中国现代文学与政治等同起来,有点像是一种束缚。因为至少在冷战阶段,意识形态同样左右着西方人的判断力,评论者与读者如果不是专家,通常会认为20世纪中国文学充斥着独裁政治的信息,缺少风格,亦缺少精神上的复杂性。但是,正如全世界的文学一样,现代中国文学是历史、人性与美学的复合;反映出的东西远较其政治背景为多。尽管这本很有价值的选集把政治层面放在第一位,但亦有其他文学深度在其中渗透出微微的光亮。

Drawing on the work of numerous translators, “The Big Red Book of Modern Chinese Literature” is divided into three parts, devoted to the Republican Era (1911-49), the Revolutionary Era (1949-76) and the Post-Mao Era (1976 to the present). The first section among others, the authors of the first half of the 20th century who form the “patriotic canon” of modern Chinese writers (Lu Xun, Mao Dun, Ba Jin). Associated with the New Culture Movement of the 1910s and 1920s (which, alongside other aims, sought to create a serious literature in vernacular Chinese that would forge a vigorous national consciousness), their writing denounced the poverty, injustice and political chaos that afflicted the country from the late 19th century onward. The anthology’s second section showcases a handful of “revolutionary” works, including a model opera, a peasant writer’s short story and Mao’s own unabashedly classical poetry. The third section can be read as a creative reaction against the strictures of the Mao era, and of the Cultural Revolution in particular. Here we encounter the return of ambiguity and nuance in the poetic language of Bei Dao; Mo Yan’s -busting fiction, packed with sex and gore; and the linguistic playfulness of Ma Yuan and Che Qianzi.

这本《中国现代文学大红宝书》(The Big Red Book of Modern Chinese Literature)是许多翻译家工作的成果,分为三部分,分别是民国时期(1911-1949)、革命时期(1949-1976)和后毛泽东时期(1976至今)。第一部分中特别选入了20世纪上半叶奠定了“爱国主义经典”的中国现代作家(鲁迅、茅盾,巴金)的作品。他们与19世纪10年代与20年代中国的新文化运动密切相关(新文化运动的首要目标就是在白话文的基础上创造一种严肃文学,促进民族的觉醒),他们的作品谴责贫穷与不公,乃至自从19世纪末以来困扰着这个国家的政治动荡。选集的第二部分是一小批“革命”作品,包括样板戏、一位农民诗人的短篇小说,以及毛泽东本人大气的诗词作品。第三部分可以被视为对毛泽东时期,特别是“文革”时期严苛约束的创意反拨。这一部分里收入了北岛诗意的语言、莫言充满性爱与流血的禁忌题材小说,以及马原和车前子的语言游戏,他们重新把模糊与微妙带回了文学之中。

Huang’s selections also accommodate literary innovators who challenge the idea of modern Chinese literature as dominated by politics. Our understanding of writers celebrated for their sociopolitical commentary, meanwhile, is complicated by the inclusion of works that are whimsical and intimate as well as those engaged in fierce denunciations of Chinese society. Rather than include Yu Dafu’s best-known short story, “Sinking” (a melodramatic first-person narration by a Chinese student in Japan in the early 1920s that blurs an individual’s sexual inferiority complex into a collective sense of national humiliation), Huang chooses a movingly low-key essay about Yu’s struggles as a penniless writer in Shanghai. Commendably, Huang himself has translated several of the more recherché entries.

黄运特的选择亦兼顾了那些挑战现代中国文学中“政治决定文学”理念的创新者们。对于那些以评议社会政治而闻名的作者,本书一方面收入他们激烈批判中国社会的作品,同时亦收入了他们异想天开而私人化的作品,从而加深了我们对他们的理解。比如,书中没有收入郁达夫最著名的短篇小说《沉沦》(19世纪20年代一个留日的中国学生感伤的第一人称叙事,把他的性自卑情结与国家耻辱感的集体情绪混合在一起),而是选了一篇感人、低调的散文,讲述身无分文的作家郁达夫在上海挣扎求生的经历。值得一提的是,黄运特自己还动手翻译了好几篇冷门的文章。

In the pre-1949 section, the standout is an excerpt from the novel “Tales of Hulan River” by Xiao Hong, a loosely left-wing female writer who died tragically young in 1942, when she was only 30 years old. Xiao Hong’s close male contemporary, Ba Jin, achieved much greater fame in his lifetime for his emotional denunciations of Confucianism in novels like “Family,” but Xiao Hong’s laconically detailed account of local superstition in her birthplace in China’s frozen northeast is much more effective as an attack on the mindless inhumanity of Chinese conservatism: “Spring, summer, autumn, winter — the seasonal cycle continues inexorably, and always has since the beginning of time. Wind, frost, rain, snow; those who can bear up under these forces manage to get by; those who cannot must seek a natural solution. This natural solution is not so very good, for these people are quietly and wordlessly taken from this life and this world.”

在1949年之前的部分,特别精彩的是萧红的小说《呼兰河传》的节选。萧红大体上可算作是一位左翼作家,1942年不幸英年早逝,只有30岁。萧红的同龄好友巴金凭着《家》等感伤地谴责封建制度的小说,获得了比萧红大得多的声誉;但萧红对故乡——中国东北一个寒冷的村庄——地方迷信充满细节的简洁描写,却是对毫无人性的中国保守势力更有力的谴责:“春夏秋冬,一年四季来回循环地走,那是自古也就这样的了。风霜雨雪,受得住的就过去了,受不住的,就寻求着自然的结果。那自然的结果不大好,把一个人默默地一声不响地就拉着离开了这人间的世界了。”

Much of the pre-1949 poetry is interesting mainly as literary history, chronicling the break with the classical past. While these early-20th-century poets clearly reveled in new freedoms of form and expression, the writing sometimes veers into self-indulgent romanticism (“I am a patch of cloud in the sky/Casting by chance a shadow on your heart”). The two short stanzas of Bian Zhilin’s “Loneliness,” however, are superbly desolate, beguiling the reader with a na pastoral start before moving to a bleak conclusion.

许多1949年以前的诗歌主要是因其具有文学史上的价值而有趣,那是中国诗歌与古典传统发生断裂的时代。这些20世纪初的诗歌显然令诗人们在全新的形式与表达的自由中狂欢,他们笔下的诗句有时不免陷入放纵的浪漫主义(“我是天空里的一片云,偶尔投影在你的波心”)。卞之琳的两首短诗《寂寞》则有一种庄严的凄凉,开头以天真的田园风光魅惑着读者,但最终以凄凉收场。

The gender balance here is sharply skewed toward male writers. This would not be surprising for a book of imperial Chinese literature, but in a collection of modern writing the disequilibrium need not be so marked. After all, the emergence of the female writer as a public personality early in the last century was one of the defining features of a newly modern Chinese literature. The most glaring omission is surely Zhang Ailing, also known as Eileen Chang, a sophisticated psychological modernist celebrated by Sinophone readers for her intricately oppressive tales of Shanghai domesticity. Lu Yin, Ru Zhijuan and Xu Xiaobin also deserve

选集中的性别比例明显偏向男性作者。这种失衡对于封建时期的中国文学来说并不惊人,但是对于一个现代文学的选集来说却过于醒目。毕竟,上世纪初,女性作家开始成为公众人物是中国现代新文学的重要特征之一。最明显的缺失显然是张爱玲,她是一位深刻的、刻画人物心理的现代主义作家,讲述上海家庭生活的故事,风格极为压抑,备受华语读者推崇。此外芦隐、茹志鹃、徐小斌等人的作品亦值得收入。

In his choices for the 1990s and beyond, Huang favors poetry, neglecting the tough, individualistic urban fiction of writers like Dong Xi, Han Dong, Xu Zechen and Zhu Wen, whose work chronicles the disaffected restlessness of contemporary China’s consumer society.

在选择20世纪90年代及之后的作品时,黄运特更为青睐诗歌,忽略了那些风格严峻而个人化的都市小说作家,诸如东西、韩东、徐则臣和朱文,他们的作品记载了当代中国消费社会人们不满的焦虑情绪。

These quibbles aside, it’s heartening to see a serious publisher, one whose list is geared to the general reader, invest in an anthology that manages to combine the established canon with less-well-known selections. The breadth and variety of “The Big Red Book of Modern Chinese Literature” will, one hopes, encourage new readers to explore more Chinese literature in full translations.

虽有上述这些吹毛求疵,看到一家严肃的、面向普通读者的出版社投资出版这样一部选集,把经典作品与罕为人知的作品收集在一起,实在令人振奋。希望《中国现代文学大红宝书》内容的广度与丰富性可以鼓励更多新读者去探索中国文学的完整译本。