(单词翻译:单击)

Last week, after a long period of stupidity from the corporate world, three astonishingly sensible things passed over my screen all at once.

不久前,在忍受了一段较长时间的企业界愚蠢后,三件明智得令人吃惊的事情出现在我的屏幕上。

Two of them came from small companies, but the third came from one of the world’s largest — and recently one of the least popular — organisations: Amazon.

其中两件事来自小公司,但是第三件事来自全世界最大的企业之一(近来也是最受非议的企业之一)——亚马逊(Amazon)。

The first example was sent to me from a reader in South Africa, who had just landed a new job and had to sign the company’s code of conduct. This read: “DO THE RIGHT THING, AT THE RIGHT TIME, WITHOUT FEARING THE RISKS.” That was it.

第一个例子是南非一个读者发给我的,该读者刚刚找到了一份新工作,必须在新公司的行为准则上签字。准则写道:“在正确的时间,做正确的事,不要担心风险。”就这么简短。

Even though the statement is unspecific, it is a big improvement on the usual interminable list of don’ts. Most codes of conduct are so long that the only intelligent thing for an employee to do is tick the box at the end without having read a word (thus disobeying the code before they’ve even started) and forget all about it. A single scary sentence in block capitals is an improvement as at least it conveys the general idea that wrongdoing is not the thing.

尽管这个声明比较笼统,但它相对于常见的冗长禁令清单是一个巨大改进。多数行为准则都没完没了,以至于员工唯一明智的做法就是一个字也不看、直接在结尾的方格打勾(从而在尚未开始工作前便已违反了行为准则),然后把准则彻底抛诸脑后。以粗体大写字母写下一句唬人的话是一种改进,因为至少它传达了“不当行为不好”这层大意。

The next example came from a small Australian hedge fund looking for a new hire. Instead of spouting the usual nonsense about proactive team players and skillsets, it said it wanted someone “(a) very bright (b) interested in the investment process, and (c) most importantly curious”. It added: “What we really want is a bullshit detector” — for which it specifies an aptitude for maths and science.

第二个例子来自澳大利亚一个正在招募新员工的小型对冲基金。该机构并未滔滔不绝地讲述通常招聘广告所说的废话,有关积极主动的团队精神和岗位技能之类,而是称,希望新员工具备“1.非常聪明、2.对投资过程感兴趣、以及3.最重要的是要有好奇心”。它补充称:“我们真正想要的是胡扯探测器”——这意味着新员工需要具备数学和理科天赋。

It wound up with the warning that “being a small organisation you are inevitably ‘long’ us as we will be ‘long’ you. There is career risk. This can be good and bad. If you do well and we do well it might be very good. If either of those things don’t play out this might wind up being a bad career choice.”

最后该基金警告称,“作为一家小型机构,你不可避免地要‘做多’我们,因为我们也将‘做多’你。这里存在职业风险。可能好也可能坏。如果你做得好,我们也做得好,结果可能会非常好。如果两者均不尽理想,结局也许是一个糟糕的职业选择。”

This is honest, funny, accurate and helpful. It almost makes me want to apply; if I were any good at science, I just might.

这话说得实在、风趣、准确又有益。这几乎让我也想去应聘;如果我有那么一点点擅长理科的话,我也许真的会去。

Both examples, from Machi.biz and Bronte Capital respectively, show how big companies could do things better. Yet I fear that if either of these outfits ever gets big, they will forget how to be sensible. Size means compliance and HR departments, which ensure that good sense — let alone personality or sharpness — are eliminated.

来自Machi.biz和Bronte Capital的这两个例子,表明了大公司如何能够做得更好。但我担心,一旦这两家机构做大了,它们将忘记如何做到明智。规模意味着合规和人力资源部门,这确保了良好判断力被淘汰,更不用说个性或棱角了。

Yet then there is Amazon, which this week has become my pin-up for the no-nonsense large organisation.

不过,接下来的例子是亚马逊(Amazon),最近它成了我眼中不说废话的大型机构的模范。

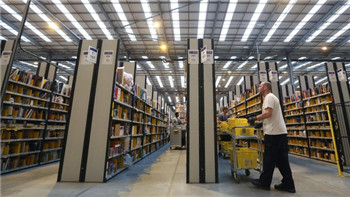

For a couple of years we’ve known (thanks to an article in the FT) that the retailer is mean to its warehouse workers. Now we know it is hard on its office workers, too. Yet as I read the latest article in the New York Times and clicked through to the company’s 14 principles, instead of being repulsed I found myself cheering its good sense.

两年前我们就知道这家零售商对其仓库员工十分刻薄。如今我们知道,亚马逊对其办公室职员也冷酷无情。不过,在阅读《纽约时报》(New York Times)最新的那篇文章时我点击浏览了该公司的14条原则,我非但没感到反感,反而为它的明智合理叫好。

Principle #9 is frugality, which I’ve never before seen held up like this. Of course leaders should be frugal — it’s not their money they are spending. Another principle reads: “Have backbone; disagree and commit.” I like this one too. In most companies everyone thinks just the same (despite the pretence of diversity) and those who don’t, keep quiet.

第9条原则是节俭——我从没看到哪家公司如此重视过。当领导的当然应该节俭——他们花的不是自己的钱。另一条原则是:“有骨气;敢于不同意、有担当。”我也喜欢这一条。在大多数公司,每个人想得都一样(尽管它们假装多元化),而观点不同的人保持沉默。

Yet the principle that had me throwing my hat in the air said leaders “are right, a lot”.

不过,最让我为之振奋的原则是:领导“是正确的,在很多情况下”。

To anyone not well schooled in corporate nonsense this might seem a bit obvious. But most companies have so fallen for the trendy idea of “fail fast, fail often” they have started to talk as if being wrong were superior to being right.

对于没接受过企业废话洗礼的人来说,这一条也许看起来有点显而易见。但是,大多数公司已经如此沉迷于“快速失败、经常失败”这种新潮观点,以至于它们听上去仿佛是做错比做对更好。

So what are we to make of the fact that this company, which is so subversively sensible, is so horrid to its workers? I have a nasty feeling the two things are connected. Amazon can afford to be honest because it isn’t trying to pretend to be nice. Founder Jeff Bezos has never had any truck with cuddly: “Our culture is friendly and intense, but if push comes to shove we’ll settle for intense,” he once said. The rest of the corporate world has built a business model that rests on the idea of happy workers.

那么,我们该如何理解一家颠覆性明智的公司对其员工如此可恶呢?我有种不好的感觉——这两件事是相互关联的。亚马逊能够做到坦诚,是因为它根本不试图假装亲善。亚马逊创始人杰夫·贝索斯 (Jeff Bezos)从不使用讨人欢心的把戏。他曾表示,“我们的文化是友善和紧张的,但在紧要关头,我们只能退而求其次地选择紧张。”其他企业则构建了一种基于员工幸福的商业模式。

Because this is partly a lie — all corporations must extract their pound of flesh to turn a profit — they are restricted in what they can say. Hence the empty guff about passion and fun.

因为这在一定程度上必然是谎言——所有企业都必须剥削员工来盈利——所以它们能说的话受到限制。于是就出现了大量关于激情和乐趣的空洞废话。

The lesson from Amazon blows away one of the biggest lies of management. The stakeholder model pretends you can have it all — customers, shareholders and employees can all do well at the same time.

亚马逊的教训打破了管理学最大的谎言之一。利益相关者模式假装你可以面面俱到——客户、股东和员工都可以同时成为赢家。

Amazon is a throwback to the old style of capitalism, in which there was a trade-off. As I read the NYT article last week it was late at night and I was sitting up in bed ordering weird lightbulbs and irregular screws, knowing they would arrive, at a discounted price, before lunch the next day.

亚马逊回归到旧式的资本主义——有得必有失。我阅读《纽约时报》的文章时正值深夜,我坐在床上订购奇怪的灯泡和不规则的螺丝,我知道这些商品能以折扣价在第二天午饭前送到我手中。

At Amazon, the customer wins — and the employee does not. The company may not have chosen the most morally acceptable trade-off. But it has laid bare this fact of economic life: when some win, others lose.

在亚马逊,客户是赢家——员工不是。该公司也许没有选择在道德上最可接受的取舍。但是它彰显了经济生活中的一个事实——有人赢,必然有人输。