(单词翻译:单击)

“To err is human. To blame someone else is politics.” Hubert H. Humphrey’s aphorism came to mind as I was reading “China 1945,” Richard Bernstein’s excellent history of United States policy toward China at the end of World War II. The comment is particularly apt when intractable problems provide myriad paths to failure but no clear right answer — and the civil war in China after Japan’s surrender was just such a problem. (Today, think of Syria.) The debates over China policy were acrimonious and personal, and this was several years before Joseph McCarthy lent his name to sneering political assassination.

“犯错是人性,归罪于他人则是政治,”阅读理查德·伯恩斯坦(Richard Bernstein)的《中国1945》(China 1945)时,休伯特·H·汉弗莱(Hubert H. Humphrey)的格言不禁涌上心头。这是一本关于“二战”后美国对华政策历史的精彩著作。汉弗莱的话尤其适用于那种棘手的难题,它们可以导致无数条通往失败的道路,却没有任何清晰的正确答案——日本投降后中国的内战正是这样的问题(试想如今的叙利亚)。关于中国政策的争论激烈而又充满人身攻击,几年后,约瑟夫·麦卡锡(Joseph McCarthy)的名字就成了政治迫害的代称。

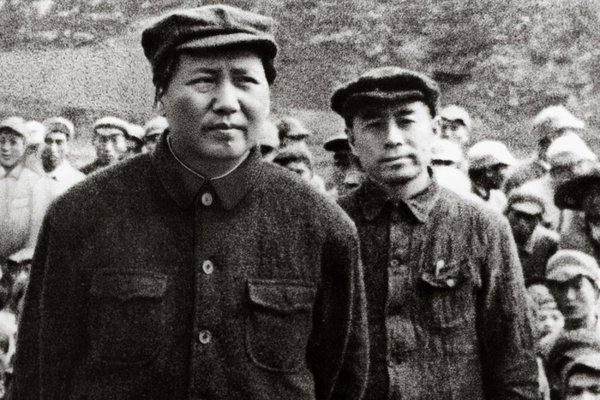

Bernstein, a student of Harvard’s John King Fairbank and a formerNew York Times reporter, covers China’s political context in 1945 like a scholar, but maintains his journalist’s eye for human drama. In 1945 American officials in China were trying to achieve three impossibly conflicting aims: prevent a civil war between Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang regime and Mao Zedong’s Communist Party; keep the United States out of any civil war that might occur; and stop the Communists and their Soviet backers from seizing control of northern China from Chiang’s government, a World War II ally. The third aim could not be accomplished without violating the second. But the second could not be seriously violated because America was, understandably, tired of war.

伯恩斯坦是哈佛大学费正清教授的学生,曾在《纽约时报》担任记者,他在本书中如学者一般记述1945年中国的政治环境,但又以记者的视角关注人性的戏剧。1945年,驻华美国官员试图达成三个自相矛盾、不可能实现的目标:其一,阻止蒋介石领导的国民党政府与毛泽东领导的共产党之间爆发内战;其二,保证美国政府不卷入可能发生的内战;其三,阻止共产党及其苏联支持者从美国“二战”期间的盟友蒋介石政府手中夺去对中国北方的控制权。除非违背第二个目标,就不可能实现第三个目标,但第二个目标又不能被严重违背,因为,可以理解,美国已经厌倦了战争。

So that left preventing civil war. Even before Japan surrendered, United States officials were trying to persuade Chiang and Mao to cease hostilities and establish a coalition government. Bernstein convincingly deems this mission doomed, though it was headed in 1946 by George Marshall, the greatest American statesman of his generation. Chiang was politically beholden to factions that could never allow sustained compromise with Mao’s Communists; and Chiang himself was bullheaded. Mao was a radical ideologue and manipulator who viewed cooperation with rivals in the same way as his role model, Joseph Stalin.

所以就只剩下阻止内战了。早在日本投降之前,美国官员就已经开始试图说服蒋介石和毛泽东放下敌意,成立联合政府。贝恩斯坦令人信服地认定,尽管这项任务在1946年是由同代美国政治家中最优秀的乔治·马歇尔(George Marshall)领导,但注定凶多吉少。蒋介石在政治上要对若干小集团负责,这些集团不可能长期对毛泽东的共产党妥协;而蒋介石本人也很顽固。毛泽东则信奉激进的意识形态,而且对于“与竞争对手合作”这种事,和他的榜样约瑟夫·斯大林(Joseph Stalin)持有同样看法。

Marshall’s eccentric predecessor, Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley, was deluded in believing that with his Oklahoma horse sense and lawyerly acumen he could broker a lasting coalition government. But in late November 1945, he abruptly resigned in frustration, publicly blaming Foreign Service Asia experts like John Paton Davies and John Stewart Service for undercutting his efforts. Hurley complained that they had unfairly criticized Chiang’s government while coddling the Communists, and scandalously accused them of disloyalty to him and their nation (apparently in that order of importance).

马歇尔的前任帕特里克·J·赫尔利(Patrick J. Hurley)大使是个性情古怪的人,有着俄克拉荷马人的判断力和律师式的聪明,他被哄骗着相信自己可以在双方之间斡旋,协助建立一个持久的联合政府。但在1945年11月底,他却带着挫败感突然辞职,还公开谴责戴维斯(John Paton Davies)和谢伟思(John Stewart Service)等美国驻外事务处的亚洲专家损害了他的努力。赫尔利抱怨,他们对蒋介石政府的指控有欠公正,同时过分纵容共产党,他还严厉地指责这些专家背叛了他,也背叛了国家(显然他认为背叛他比背叛国家更不能忍)。

There are no unalloyed heroes in Bernstein’s story. While hardly traitors, Davies and Service were guilty of serious analytic misdemeanors. They naïvely advocated accommodation of the Communists because they believed that Mao’s revolutionary movement was more democratic and nationalist than it actually was.

伯恩斯坦的故事中没有真正的英雄。但也没有什么叛徒。戴维斯和谢伟思在判断上严重失误。他们天真地宣扬与共产党和解,因为他们相信毛泽东的革命运动更民主、更民族主义,事实却非如此。

Even if Mao had entertained a temporary deal with Chiang in the late 1940s, however, he was not one to keep promises or share power. After all, he purged and tortured many of his loyal followers once he “liberated” China. No pragmatist, Mao pursued a radical agenda that left more Chinese dead than even the Japanese imperialists did. And Bernstein could have taken his critique of these American officials’ analysis one step further. When Mao finally broke with the Soviets in the late 1950s and ’60s, as some American officials predicted in 1945 that he would, he did so not because he was forsaking the Stalinist model. Quite the opposite. Mao accused Stalin’s successors — Khrushchev and Brezhnev — of insufficient support for international revolution and excessive compromise with the United States.

40年代末期,就算毛有兴趣同蒋介石缔结临时合约,他也并不是那种会信守承诺或分享权力的人。毕竟,一俟他“解放”中国之后,便开始清洗和迫害许多自己的忠实追随者。毛并不是实用主义者,他追求激进的政治进程,害死的中国人甚至比日本帝国主义还多。伯恩斯坦本可以更进一步地去批评美国官员们的分析。20世纪50到60年代,毛泽东最终同苏联决裂,美国官员们在1945年便已经预见了这一幕,但他这样做并不是因为摒弃斯大林模式。恰恰相反,毛泽东谴责斯大林的继任者赫鲁晓夫(Khrushchev)和勃列日涅夫(Brezhnev)不够支持国际革命事业,过分向美国妥协。

My main objection to Bernstein’s book is a quibble concerning part of its subtitle: “America’s Fateful Choice.” Right-wing critics blamed Truman for “losing China” to the Communists by being insufficiently supportive of Chiang. After Vietnam, left-wing academics lamented that there had been a “lost chance” for friendship with Mao, if onlyWashington had seized it. Bernstein’s subtitle suggests he will take a position in this tired debate. But he correctly rejects both positions. If any foreigners lost China to Communism, it was the rabidly anti-Communist Japanese imperialists who undercut Chiang’s legitimacy and created space for revolution. And no amount of accommodation could have turned Mao into a trusted American ally in the 1950s.

我对伯恩斯坦这本书最大的意见是对副标题的吹毛求疵——“美国命中注定的选择”。右翼评论家批评杜鲁门(Truman)没有给蒋介石足够支持,因此从共产党手中“失去了中国”。越南战争后,左派学者又哀叹失去了与毛建立友谊的“机会”,好像华盛顿真有这个机会似的。伯恩斯坦的副标题仿佛暗示自己将在这场令人厌倦的争论中选择立场。但他实事求是地对两边的立场都做了否定。如果有任何外国人把中国让给了共产主义,那也应该是疯狂反共的日本帝国主义者,他们损害了蒋介石政府的合法性,为共产党的革命创造了空间。而在50年代,没有任何和解方式可以令毛泽东投向可信的美国联盟。

Truman chose an ineffective middle road: side with Chiang, but not too much. Bernstein blames American domestic politics for this diluted policy, and there is some truth to that. But Truman had no better option. He gave Chiang a fighting chance to secure his own country without dragging a war-weary America into a huge civil conflict on the Soviets’ doorstep, and Chiang failed. Direct American intervention would have been the wrong war in the wrong place at the wrong time. Yet simply abandoning wartime allies to insurrection would have harmed Washington’s reputation for resolve.

杜鲁门选择了无效的中间道路:和蒋介石站在统一战线,但是不提供太多支持。伯恩斯坦认为是美国的内政导致了这种无力的政策,这个观点有几分正确性。但杜鲁门并没有更好的选择。他给了蒋介石一个保卫国家的战斗机会,同时又没有把已经厌倦战争的美国拖入一场在苏联门口发生的大内战中去,而蒋介石失败了。当时如果美国进行干预,将会是一场在错误的时间、错误的地点发生的错误的战争。但是如果放任战时盟国陷入内乱,又会损害华盛顿的信誉。

More important, indifference to Communism’s spread in China would have undercut the administration’s domestic effort to mobilize support for Cold War strategies in geostrategically more important places like Europe, Japan and the Middle East. Truman’s options were “bad,” “worse” and “terrible.” Truman wisely chose “bad.” Not all global problems have American solutions, and often the best policy choice is to manage and minimize costs. Moderation in the defense of liberty is no vice.

更重要的是,当时政府正在国内欧洲、日本和中东等从地缘政治而言更重要的地带为巩固“冷战”战略而进行努力,如果放任共产主义在中国蔓延,政府的这些工作就将受到损害。杜鲁门面临的选择有“糟糕”、“更糟”和“糟糕极了”。杜鲁门明智地选了“糟糕”。美国并不能解决所有全球问题,而最好的政治选择通常是能够控制成本、把代价减少到最低程度的选择。在自由的保护之下深思熟虑并不是什么坏事。