(单词翻译:单击)

双语小说

SOMETIMES, I GOT BEHIND the wheel of my Ford, rolled down the windows, and drove for hours, from the East Bay to the South Bay, up the Peninsula and back. I drove through the grids of cottonwood-lined streets in our Fremont neighborhood, where people who’d never shaken hands with kings lived in shabby, flat one-story houses with barred windows, where old cars like mine dripped oil on blacktop driveways. Pencil gray chain-link fences closed off the backyards in our neighborhood. Toys, bald tires, and beer bottles with peeling labels littered unkempt front lawns. I drove past tree-shaded parks that smelled like bark, past strip malls big enough to hold five simultaneous Buzkashi tournaments. I drove the Torino up the hills of Los Altos, idling past estates with picture windows and silver lions guarding the wrought-iron gates, homes with cherub fountains lining the manicured walkways and no Ford Torinos in the drive ways. Homes that made Baba’s house in Wazir Akbar Khan look like a servant’s hut.

I’d get up early some Saturday mornings and drive south on Highway 17, push the Ford up the winding road through the mountains to Santa Cruz. I would park by the old lighthouse and wait for sunrise, sit in my car and watch the fog rolling in from the sea. In Afghanistan, I had only seen the ocean at the cinema. Sitting in the dark next to Hassan, I had always wondered if it was true what I’d read, that sea air smelled like salt. I used to tell Hassan that someday we’d walk on a strip of seaweed-strewn beach, sink our feet in the sand, and watch the water recede from our toes. The first time I saw the Pacific, I almost cried. It was as vast and blue as the oceans on the movie screens of my childhood.

Sometimes in the early evening, I parked the car and walked up a freeway overpass. My face pressed against the fence, I’d try to count the blinking red taillights inching along, stretching as far as my eyestould see. BMWs. Saabs. Porsches. Cars I’d never seen in Kabul, where most people drove Russian Volgas, old Opels, or Iranian Paikans.

Almost two years had passed since we had arrived in the U.S., and I was still marveling at the size of this country, its vastness. Beyond every freeway lay another freeway, beyond every city another city hills beyond mountains and mountains beyond hills, and, beyond those, more cities and more people.

Long before the Roussi army marched into Afghanistan, long before villages were burned and schools destroyed, long before mines were planted like seeds of death and children buried in rock-piled graves, Kabul had become a city of ghosts for me. A city of harelipped ghosts.

America was different. America was a river, roaring along, unmindful of the past. I could wade into this river, let my sins drown to the bottom, let the waters carry me someplace far. Someplace with no ghosts, no memories, and no sins.

If for nothing else, for that, I embraced America.

THE FOLLOWING SUMMER, the summer of 1984--the summer I turned twenty-one--Baba sold his Buick and bought a dilapidated ’71 Volkswagen bus for $550 from an old Afghan acquaintance who’d been a high-school science teacher in Kabul. The neighbors’ heads turned the afternoon the bus sputtered up the street and farted its way across our lot. Baba killed the engine and let the bus roll silently into our designated spot. We sank in our seats, laughed until tears rolled down our cheeks, and, more important, until we were sure the neighbors weren’t watching anymore. The bus was a sad carcass of rusted metal, shattered windows replaced with black garbage bags, balding tires, and upholstery shredded down to the springs. But the old teacher had reassured Baba that the engine and transmission were sound and, on that account, the man hadn’t lied.

On Saturdays, Baba woke me up at dawn. As he dressed, I scanned the classifieds in the local papers and circled the garage sale ads. We mapped our route--Fremont, Union City, Newark, and Hayward first, then San Jose, Milpitas, Sunnyvale, and Campbell if time permitted. Baba drove the bus, sipping hot tea from the thermos, and I navigated. We stopped at garage sales and bought knickknacks that people no longer wanted. We haggled over old sewing machines, one-eyed Barbie dolls, wooden tennis rackets, guitars with missing strings, and old Electrolux vacuum cleaners. By midafternoon, we’d filled the back of the VW bus with used goods. Then early Sunday mornings, we drove to the San Jose flea market off Berryessa, rented a spot, and sold the junk for a small profit: a Chicago record that we’d bought for a quarter the day before might go for $1, or $4 for a set of five; a ramshackle Singer sewing machine purchased for $10 might, after some bargaining, bring in $25.

By that summer, Afghan families were working an entire section of the San Jose flea market. Afghan music played in the aisles of the Used Goods section. There was an unspoken code of behavior among Afghans at the flea market: You greeted the guy across the aisle, you invited him for a bite of potato bolani or a little qabuli, and you chatted. You offered tassali, condolences, for the death of a parent, congratulated the birth of children, and shook your head mournfully when the conversation turned to Afghanistan and the Roussis--which it inevitably did. But you avoided the topic of Saturday. Because it might turn out that the fellow across the isle was the guy you’d nearly blindsided at the freeway exit yesterday in order to beat him to a promising garage sale.

The only thing that flowed more than tea in those aisles was Afghan gossip. The flea market was where you sipped green tea with almond kolchas, and learned whose daughter had broken off an engagement and run off with her American boyfriend, who used to be Parchami--a communist--in Kabul, and who had bought a house with under-the-table money while still on welfare. Tea, Politics, and Scandal, the ingredients of an Afghan Sunday at the flea market.

I ran the stand sometimes as Baba sauntered down the aisle, hands respectfully pressed to his chest, greeting people he knew from Kabul: mechanics and tailors selling hand-me-down wool coats and scraped bicycle helmets, alongside former ambassadors, out-of-work surgeons, and university professors.

One early Sunday morning in July 1984, while Baba set up, I bought two cups of coffee from the concession stand and returned to find Baba talking to an older, distinguished-looking man. I put the cups on the rear bumper of the bus, next to the REAGAN/BUSH FOR ’84 sticker.

“Amir,” Baba said, motioning me over, “this is General Sahib, Mr. Iqbal Taheri. He was a decorated general in Kabul. He worked for the Ministry of Defense.”

Taheri. Why did the name sound familiar? The general laughed like a man used to attending formal parties where he’d laughed on cue at the minor jokes of important people. He had wispy silver-gray hair combed back from his smooth, tanned forehead, and tufts of white in his bushy eye brows. He smelled like cologne and wore an iron-gray three-piece suit, shiny from too many pressings; the gold chain of a pocket watch dangled from his vest.

“Such a lofty introduction,” he said, his voice deep and cultured. “_Salaam, bachem_.” Hello, my child.

“_Salaam_, General Sahib,” I said, shaking his hand. His thin hands belied a firm grip, as if steel hid beneath the moisturized skin.

“Amir is going to be a great writer,” Baba said. I did a double take at this. “He has finished his first year of college and earned A’s in all of his courses.”

“Junior college,” I corrected him.

有时,我会开着我的福特,摇下车窗,一连开几个钟头,从东湾到南湾,前往半岛区[1]东湾(EastBay)、南湾(SouthBay)和半岛区(Penisula)均为旧金山城区。[1],然后开回来。我会驶过弗里蒙特附近那些纵横交错、棋盘似的街道,这里的人们没有和国王握过手,住在破旧的平房里面,窗户破损;这里的旧车跟我的一样,滴着油,停在柏油路上。我们附近那些院子都被铅灰色的铁丝栅栏围起来,乱糟糟的草坪上到处扔着玩具、汽车内胎、标签剥落的啤酒瓶子。我驶过散发着树皮味道的林阴公园,驶过巨大的购物广场,它们大得足可以同时举办五场马上比武竞赛。我开着这辆都灵,越过罗斯?阿托斯的山丘,滑行过一片住宅区,那儿的房子有景观窗,银色的狮子守护在锻铁大门之外,塑有天使雕像的喷泉在修葺完善的人行道排开,停车道上没有福特都灵。这里的房子使我爸爸在喀布尔的房子看起来像仆人住的。

有时候,在星期六我会早起,朝南开上17号高速公路,沿着蜿蜒的山路前往圣克鲁斯。我会在旧灯塔旁边停车,等待太阳升起,坐在我的轿车里面,看着雾气在海面翻滚。在阿富汗,我只在电影里面见过海洋。在黑暗中,挨哈桑坐着,我总是寻思,我在书上看到,说海水闻起来有盐的味道,那是不是真的?我常常告诉哈桑,有朝一日,我们会沿着海藻丛生的海滩散步,让我们的脚陷进沙里,看着海水从我们的脚趾退去。第一次看到太平洋时,我差点哭起来。它那么大,那么蓝,跟我孩提时在电影屏幕上看到的一模一样。

有时候,夜幕初降,我会把车停好,爬上横跨高速公路的天桥。我的脸压着护栏,极目远望,数着那缓缓移动的闪闪发亮的汽车尾灯,宝马,绅宝,保时捷,那些我在喀布尔从来没见过的汽车,在那儿,人们开着俄国产的伏尔加,破旧的欧宝,或者伊朗出产的培康。

我们来到美国几乎快两年了,我仍为这个国家辽阔的幅员惊叹不已。高速公路之外,还有高速公路,城市之外还有城市,山脉之外还有峰峦,峰峦之外还有山脉,而所有这些之外,还有更多的城市,更多的人群。

早在俄国佬的军队入侵阿富汗之前,早在乡村被烧焚、学校被毁坏之前,早在地雷像死亡的种子那样遍布、儿童被草草掩埋之前,对我来说,喀布尔就已成了一座鬼魂之城,一座兔唇的鬼魂萦绕之城。

美国就不同了。美国是河流,奔腾前进,往事无人提起。我可以进这条大川,让自己的罪恶沉在最深处,让流水把我带往远方,带往没有鬼魂、没有往事、没有罪恶的远方。

就算不为别的,单单为了这个,我也会拥抱美国。

接下来那个夏天,也就是1984年夏天——那年夏天我满21岁——爸爸卖掉他的别克,花了550美元,买了一辆破旧的1971年出厂的大众巴士,车主是阿富汗的老熟人了,先前在喀布尔教高中的科学课程。那天下午,巴士轰鸣着驶进街道,“突突”前往我们的停车场,邻居都把头转过来。爸爸熄了火,让巴士安静地滑进我们的停车位。我们坐在座椅上,哈哈大笑,直到眼泪从脸颊掉下来,还有,更重要的是,直到我们确信没有任何邻居在观望,这才走出来。那辆巴士是一堆废铁的尸体,黑色的垃圾袋填补破裂的车窗,光秃秃的轮胎,弹簧从座椅下面露出来。但那位老教师一再向爸爸保证,引擎和变速器都没有问题,实际上,那个家伙没有说谎。

每逢星期六,天一亮爸爸就喊我起来。他穿衣的时候,我浏览本地报纸的分类广告栏,圈出车库卖场的广告。我们设定线路——先到弗里蒙特、尤宁城、纽瓦克和海沃德,接着是圣荷塞、米尔皮塔斯、桑尼维尔,如果时间许可,则再去坎贝尔。爸爸开着巴士,喝着保温杯里面的热红茶,我负责引路。我们停在车库卖场,买下那些原主不再需要的二手货。我们搜罗旧缝纫机,独眼的芭比娃娃,木制的网球拍,缺弦的吉他,还有旧伊莱克斯吸尘器。下午过了一半,我们的大众巴士后面就会塞满这些旧货。然后,星期天清早,我们开车到圣荷塞巴利雅沙跳蚤市场,租个档位,加点微薄的利润把这些垃圾卖出去:我们前一天花二毛五分买来的芝加哥唱片也许可以卖到每盘一元,或者五盘四元;一台花十元买来的破旧辛格牌缝纫机经过一番讨价还价,也许可以卖出二十五元。

到得那个夏天,阿富汗人已经在圣荷塞跳蚤市场占据了一整个区域。二手货区域的通道上播放着阿富汗音乐。在跳蚤市场的阿富汗人中间,有一套心照不宣的行为规范:你要跟通道对面的家伙打招呼,请他吃一块土豆饼或一点什锦饭,你要跟他交谈。要是他家死了父母,你就好言相劝;要是生了孩子你就道声恭喜;当话题不可避免地转到阿富汗人和俄国佬,你就悲伤地摇摇头。但是你得避免说起星期六的事情,因为对面那人很可能就是昨天在高速公路出口被你超车挡住、以致错过一桩好买卖的家伙。

在那些通道里,惟一比茶更流行的是阿富汗人的流言。跳蚤市场是这样的地方,你可以喝绿茶,吃杏仁饼,听人说谁家的女儿背弃婚约,跟美国男友私奔去了;谁在喀布尔用黑钱买了座房子,却还领救济金。茶,政治,丑闻,这些都是跳蚤市场的阿富汗星期天必备的成分。

有时我会看管摊位,爸爸则沿着过道闲逛。他双手庄重地放在胸前,跟那些在喀布尔认识的熟人打招呼:机械师和裁缝兜售有擦痕的自行车头盔和旧羊毛衫,过道两边是原来的外交官、找不到工作的外科医生和大学教授。

1984年7月某个星期天清早,爸爸在清理摊位,我到贩卖处买了两杯咖啡,回来的时候,发现爸爸在跟一位上了年纪、相貌出众的先生说话。我把杯子放在巴士后面的保险杠上,紧邻里根和布什竞选1984年总统的宣传画。

“阿米尔,”爸爸说,示意我过去:“这是将军大人,伊克伯?塔赫里先生,原来住在喀布尔,得过军功勋章,在国防部上班。”

塔赫里。这个名字怎么如此熟悉? 将军哈哈干笑,通常在宴会上,每当重要人物说了不好笑的笑话,人们就会听到这样的笑声。他一头银发整齐地梳向后面,露出平滑的黄铜色前额,浓密的眉毛中有撮撮白色。他身上闻起来有古龙水的香味,穿着铁灰色的三排扣套装,因为洗熨了太多次而泛着亮光,背心上面露出一根怀表的金链子。

“这样的介绍可不敢当。”他说,他的声音低沉而有教养。“你好,我的孩子。”

“你好,将军大人。”我说,跟他握手。他的手貌似瘦弱,但握得很有力,好像那油亮的皮肤下面藏着钢条。

“阿米尔将会成为一个了不起的作家。”爸爸说。我愣了一下才反应过来。“他刚念完大学一年级,考试门门都得优。”

“是专科学校。”我纠正他。

作品周边

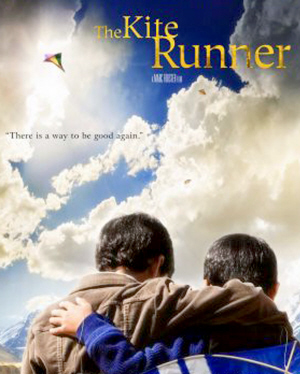

内容简介

12岁的阿富汗富家少爷阿米尔与仆人哈桑情同手足。然而,在一场风筝比赛后,发生了一件悲惨不堪的事,阿米尔为自己的懦弱感到自责和痛苦,逼走了哈桑,不久,自己也跟随父亲逃往美国。

成年后的阿米尔始终无法原谅自己当年对哈桑的背叛。为了赎罪,阿米尔再度踏上暌违二十多年的故乡,希望能为不幸的好友尽最后一点心力,却发现一个惊天谎言,儿时的噩梦再度重演,阿米尔该如何抉择?

故事如此残忍而又美丽,作者以温暖细腻的笔法勾勒人性的本质与救赎,读来令人荡气回肠。

作者简介

卡勒德·胡赛尼(Khaled Hosseini),1965年生于阿富汗喀布尔市,后随父亲迁往美国。胡赛尼毕业于加州大学圣地亚哥医学系,现居加州。“立志拂去蒙在阿富汗普通民众面孔的尘灰,将背后灵魂的悸动展示给世人。”著有小说《追风筝的人》(The Kite Runner,2003)、《灿烂千阳》(A Thousand Splendid Suns,2007)、《群山回唱》(And the Mountains Echoed,2013)。作品全球销量超过4000万册。2006年,因其作品巨大的国际影响力,胡赛尼获得联合国人道主义奖,并受邀担任联合国难民署亲善大使。

精选评论

热门评论

对友谊最大的误解,就是认为它是万能的(来自豆瓣网友:谢长留)

我时常幻想自己是来自未来的,这样,有一天我面对未来某一时刻的突然变化,就会更从容,面对陈年往事也会更慷慨。但,我更适合平庸,如寻常人一样琐碎繁杂的生活,对时间的细枝末节斤斤计较。

既然无法预知未来,那么人更多的开始依赖回忆,甚至靠那些零星琐碎的回忆支撑往后的日子,有些回忆很美好,有些回忆很心酸,有些回忆让人长大,有些回忆让人显得很无知,有些回忆慢慢泛黄,有些回忆仿佛就在昨天。有些故事也总是从儿时的回忆展开。

我对阿富汗以及周边连年征战的国家和他们的历史毫无兴趣,对我而言,那里的人民是可怜的,那里的政府是可悲的,所以当《追风筝的人》这个故事一点一点展现在我面前的时候,我并没准备好接受一个平静的,也曾春暖花开,羊肉串香飘整条街的画面,更没想到那里的孩子也可以无忧无虑的追逐风筝。

所以当身为少爷的阿米尔和他的仆人哈桑情同手足的画面一出现,所有读者不禁感叹,少年时的友谊是那么充满力量,干净而持久的。他们总是并肩而行,每当阿米尔被人欺负的时候,哈桑总是义无反顾的站出来保护,很多人说这是哈桑天生的奴性,这种观点我不赞同,我看见他们之间分明有一道友谊的光芒在闪耀。

当阿米尔问哈桑为什么确定自己一定会知道被切断绳线的风筝的掉落地的时候,哈桑肯定的对阿米尔说,我就是知道,然后反问,我什么时候骗过你。阿米尔轻声说,我怎么知道有没有骗过我。哈桑发誓,为了你,我宁可啃烂泥。阿米尔进一步确定,你真的会为我啃烂泥?哈桑坚定的说,我肯定,然后又说,但是你又怎么能忍心让我啃烂泥。所以读者心中所向往的也就是我们每个人心中那个潮湿的童年印象,总是和自己最亲密的伙伴,席地而坐,互相盟誓,发誓为对方,甘愿上刀山下火海。就如同哈桑洋溢着笑脸对阿米尔说的那样:为你,千千万万遍。

然而事实上却是这样的:他是主人,他是仆人;他是普什图,他是哈扎拉;他是逊尼派,他是什叶派,从他们出生的那一刻起,他们的命运就被这些他们所不能理解的标签所分隔开来,尽管他们是亲密无间的朋友,尽管他们事实上拥有同一位父亲。无论是平凡的阿米尔和哈桑,还是高高在上的查希尔国王或者卡尔扎伊,都不得不接受社会为他们预定的座位——阿米尔不再是阿米尔,哈桑也不再是哈桑,他们必须戴上社会分给他们的面具。

哈桑总是说“为你,千千万万遍”,而生性懦弱的阿米尔却选择沉默冷酷的逃避,这样的悲剧性结果并不单单是个性差异所造成的,在这些年少无知的孩子的潜意识里早已被灌输了相应于自身社会地位的“应该”与“不应该”,一个哈扎拉仆人理应为主人尽忠,而高贵的普什图少爷不值得为一个卑贱的哈扎拉仆人冒任何风险。

“阿米尔和哈桑,喀布尔的统治者”,这样的誓言只能是石榴树下的童话,“王子与贫儿”不可能成为兄弟,因为他们命中注定不平等。包括二十年后,阿米尔重返阿富汗的自我救赎行为,也只不过是在获知自己与哈桑的同父异母兄弟关系之后对身世的无奈认可,也就是说,他仍然没有证明自己已经找到了“重新成为好人的路”。

我们少年的时候,总是意气风发,三五结伴,促膝长谈。那是在我们其乐融融的环境中构建的虚拟场景,属于物理学讲究的理想状态,然而在残酷的现实面前,在微弱的友谊遇到挑战的时刻,只要有一方露出破绽,友谊的桥梁必然坍塌。

于是当阿米尔在看到哈桑被大一些的孩子欺负甚至猥亵的时候,他选择沉默和逃避;与此同时,哈桑却为了阿米尔的风筝坚定不动摇的和对手较量,对手残忍的揭示阿米尔和哈桑之间的主仆关系,哈桑大声反驳说两个人是朋友。躲在角落里不敢出现的阿米尔听到这句话不但没有一点激励也没有丝毫感动,他心底里的怯懦终于将他的灵魂吞噬,于是悲剧发生。

这就是我们对友谊最大的误解,认为它是万能的。

即使是存在这样的问题,《追风筝的人》也还是一本出色的小说。主和仆、贵族和贱民、朋友和兄弟,历史和现实,种种转变都被刻画得生动而细腻。放在历史的宏大背景下,更洞见人生和人性的复杂。

友谊和爱。

是在困难之中由弱变强的柔韧派还是在权衡利弊之中土崩瓦解的懦弱派。

谁敢真的站出来举起右手发誓,我从来没有辜负过任何一段纯粹的友谊,谁敢真的抬头挺胸说自己对朋友忠心不二。

我们总是太自信,对友谊误解,对自己的爱误解,对不可能的事信以为真。