(单词翻译:单击)

双语小说

March 1981 A young woman sat across from us. She was dressed in an olive green dress with a black shawl wrapped tightly around her face against the night chill. She burst into prayer every time the truck jerked or stumbled into a pothole, her “Bismillah!” peaking with each of the truck’s shudders and jolts. Her husband, a burly man in baggy pants and sky blue turban, cradled an infant in one arm and thumbed prayer beads with his free hand. His lips moved in silent prayer. There were others, in all about a dozen, including Baba and me, sitting with our suitcases between our legs, cramped with these strangers in the tarpaulin-covered cab of an old Russian truck.

My innards had been roiling since we’d left Kabul just after two in the morning. Baba never said so, but I knew he saw my car sickness as yet another of my array of weakness--I saw it on his embarrassed face the couple of times my stomach had clenched so badly I had moaned. When the burly guy with the beads--the praying woman’s husband--asked if I was going to get sick, I said I might. Baba looked away. The man lifted his corner of the tarpaulin cover and rapped on the driver’s window, asked him to stop. But the driver, Karim, a scrawny dark-skinned man with hawk-boned features and a pencil-thin mustache, shook his head.

“We are too close to Kabul,” he shot back. “Tell him to have a strong stomach.”

Baba grumbled something under his breath. I wanted to tell him I was sorry, but suddenly I was salivating, the back of my throat tasting bile. I turned around, lifted the tarpaulin, and threw up over the side of the moving truck. Behind me, Baba was apologizing to the other passengers. As if car sickness was a crime. As if you weren’t supposed to get sick when you were eighteen. I threw up two more times before Karim agreed to stop, mostly so I wouldn’t stink up his vehicle, the instrument of his livelihood. Karim was a people smuggler--it was a pretty lucrative business then, driving people out of Shorawi-occupied Kabul to the relative safety of Pakistan. He was taking us to Jalalabad, about 170 kilometers southeast of Kabul, where his brother, Toor, who had a bigger truck with a second convoy of refugees, was waiting to drive us across the Khyber Pass and into Peshawar.

We were a few kilometers west of Mahipar Falls when Karim pulled to the side of the road. Mahipar--which means “Flying Fish”--was a high summit with a precipitous drop overlooking the hydro plant the Germans had built for Afghanistan back in 1967. Baba and I had driven over the summit countless times on our way to Jalalabad, the city of cypress trees and sugarcane fields where Afghans vacationed in the winter.

I hopped down the back of the truck and lurched to the dusty embankment on the side of the road. My mouth filled with saliva, a sign of the retching that was yet to come. I stumbled to the edge of the cliff overlooking the deep valley that was shrouded in dark ness. I stooped, hands on my kneecaps, and waited for the bile. Somewhere, a branch snapped, an owl hooted. The wind, soft and cold, clicked through tree branches and stirred the bushes that sprinkled the slope. And from below, the faint sound of water tumbling through the valley.

Standing on the shoulder of the road, I thought of the way we’d left the house where I’d lived my entire life, as if we were going out for a bite: dishes smeared with kofta piled in the kitchen sink; laundry in the wicker basket in the foyer; beds unmade; Baba’s business suits hanging in the closet. Tapestries still hung on the walls of the living room and my mother’s books still crowded the shelves in Baba’s study. The signs of our elopement were subtle: My parents’ wedding picture was gone, as was the grainy photograph of my grandfather and King Nader Shah standing over the dead deer. A few items of clothing were missing from the closets. The leather-bound notebook Rahim Khan had given me five years earlier was gone.

In the morning, Jalaluddin--our seventh servant in five years--would probably think we’d gone out for a stroll or a drive. We hadn’t told him. You couldn’t trust anyone in Kabul any more--for a fee or under threat, people told on each other, neighbor on neighbor, child on parent, brother on brother, servant on master, friend on friend. I thought of the singer Ahmad Zahir, who had played the accordion at my thirteenth birthday. He had gone for a drive with some friends, and someone had later found his body on the side of the road, a bullet in the back of his head. The rafiqs, the comrades, were everywhere and they’d split Kabul into two groups: those who eavesdropped and those who didn’t. The tricky part was that no one knew who belonged to which. A casual remark to the tailor while getting fitted for a suit might land you in the dungeons of Poleh-charkhi. Complain about the curfew to the butcher and next thing you knew, you were behind bars staring at the muzzle end of a Kalashnikov. Even at the dinner table, in the privacy of their home, people had to speak in a calculated manner--the rafiqs were in the classrooms too; they’d taught children to spy on their parents, what to listen for, whom to tell.

What was I doing on this road in the middle of the night? I should have been in bed, under my blanket, a book with dog-eared pages at my side. This had to be a dream. Had to be. Tomorrow morning, I’d wake up, peek out the window: No grim-faced Russian soldiers patrolling the sidewalks, no tanks rolling up and down the streets of my city, their turrets swiveling like accusing fingers, no rubble, no curfews, no Russian Army Personnel Carriers weaving through the bazaars. Then, behind me, I heard Baba and Karim discussing the arrangement in Jalalabad over a smoke. Karim was reassuring Baba that his brother had a big truck of “excellent and first-class quality,” and that the trek to Peshawar would be very routine. “He could take you there with his eyes closed,” Karim said. I overheard him telling Baba how he and his brother knew the Russian and Afghan soldiers who worked the checkpoints, how they had set up a “mutually profitable” arrangement. This was no dream. As if on cue, a MiG suddenly screamed past overhead. Karim tossed his cigarette and produced a hand gun from his waist. Pointing it to the sky and making shooting gestures, he spat and cursed at the MiG.

I wondered where Hassan was. Then the inevitable. I vomited on a tangle of weeds, my retching and groaning drowned in the deafening roar of the MiG. WE PULLED UP to the checkpoint at Mahipar twenty minutes later. Our driver let the truck idle and hopped down to greet the approaching voices. Feet crushed gravel. Words were exchanged, brief and hushed. A flick of a lighter. “Spasseba.”

Another flick of the lighter. Someone laughed, a shrill cackling sound that made me jump. Baba’s hand clamped down on my thigh. The laughing man broke into song, a slurring, off-key rendition of an old Afghan wedding song, delivered with a thick Russian accent:

Ahesta boro, Mah-e-man, ahesta boro.(Go slowly, my lovely moon, go slowly.)

1981年3月有个年轻的妇女坐在我们对面。她穿着一身橄榄绿服装,黑色的披肩将面部包得严严实实,以抵御深夜的寒意。每逢卡车急刹或颠簸过路面的凹陷,她就会出声祈祷,每次汽车的高低起伏总伴随着她的“奉安拉之名”。她的丈夫身材矮壮,穿着破旧的裤子、天蓝色的长袍,一手抱着婴儿,空出来的那只手用拇指转动着念珠。他嘴唇开合,默默祈祷。同行的还有其他人,总共十来个,包括爸爸跟我,行李箱放在我们两腿之间,盘膝坐在被帆布包起来的后斗上,跟这些陌生人挤在一起,搭乘这辆破旧的俄国卡车。

我们凌晨两点离开喀布尔,自那时起我的内脏就已经翻江倒海。虽然爸爸没有说什么,但我知道在他眼里,晕车是孱弱无能的表现——这可以从他的脸色看出来,有好几次,我的胃收缩得厉害,忍不住呻吟,他的表情很尴尬。那个拿着念珠的矮壮男人——在祈祷的那个妇女的丈夫——问我是不是要吐了,我说可能是。爸爸把头别开。那男人掀起帆布的一角,敲敲驾驶室的窗门,要求司机停下来。司机卡林是个黑瘦的汉子,一张老鹰般的脸上留着小胡子,他摇摇头。

“我们离喀布尔太近了。”他大喊,“让他撑住。”

爸爸低声咕哝了几句。我想告诉他我很抱歉,但刹那间我满嘴唾液,喉底尝到胆汁的苦味。我转过身,揭起帆布,在行进的卡车一边呕吐起来。在我身后,爸爸正向其他乘客赔不是,仿佛晕车是犯罪,仿佛人们到了十八岁就不应该晕车。我又吐了两次,卡林这才同意停车,大部分原因还是因为担心我弄脏他的车,他赖以谋生的工具。卡林是个蛇头,从被俄国人占领的喀布尔,将人们偷偷运到相对安全的巴基斯坦,这在当时可是日进斗金的生意。他把我们载往喀布尔西南170公里外的贾拉拉巴特,他的堂兄图尔在那边接应,负责再送逃难的人一程,他有一辆更大的卡车,会载着我们通过开伯尔隘口 。

卡林把车停在路旁,这时我们在玛希帕瀑布以西数公里的地方。玛希帕——它的意思是“飞翔的鱼儿”——是一处山峰,壁立千仞,俯览着下面1967年德国人为阿富汗援建的水电站。数不清有多少次,爸爸跟我路过那座山峰,前往贾拉拉巴特,那个遍地柏树和甘蔗的城市是阿富汗人过冬的胜地。

我从卡车后面跳下去,跌跌撞撞走到路边布满尘灰的护栏。我嘴里涨满了唾液,那是快要呕吐的征兆。我蹒跚着走近悬崖边,下面的深渊被黑暗吞噬了。我弯下腰,双手撑在膝盖上,做好呕吐的准备。在某个地方传来树枝劈啪作响的声音,还有猫头鹰的叫声。寒风微微拂动树枝,吹过山坡上的灌木丛。而下面,水流在山谷淌动,传来阵阵微弱的声音。

我站在路肩上,想起我们如何离开家园,那个我生活了一辈子的地方。仿佛我们只是外出下馆子:厨房的洗碗盆堆放着沾有肉丸夹饼残渣的盘子,盛满衣物的柳条篮子摆在门廊,被褥还没叠好,衣橱里挂着爸爸做生意穿的套装。起居室的墙上仍挂着壁毯,我妈妈的图书仍拥挤地占据着爸爸书房里的架子。我们出逃的迹象很微妙:我父母的结婚照不见了,爷爷跟纳达尔国王站在死鹿之前合影的那张老照片杳然无踪。衣橱里少了几件衣服。五年前拉辛汗送我的那本皮面笔记本也消失了。

早晨,贾拉鲁丁——五年来的第七个仆人——兴许会以为我们出去散步或者兜风。我们没有告诉他。在喀布尔,你再不能相信任何人——为了获得悬赏或者因为受到威胁,人们彼此告密:邻居告发邻居,儿童揭发父母,兄弟陷害兄弟,仆人背叛主人,朋友出卖朋友。我想起歌手艾哈迈德?查希尔,他在我13岁生日那天弹奏手风琴。他和几个朋友开车去兜风,随后有人在路边发现他的尸体,有颗子弹射中他的后脑。那些人无所不在,他们将喀布尔人分成两派:告密的和没有告密的。最麻烦的是,没有人知道谁属于哪一派。裁缝给你量身时,你几句无心快语可能会让你身处波勒卡其区的黑牢。对卖肉的老板抱怨几句宵禁,你的下场很可能是在牢栏之后望着俄制步枪的枪管。甚至在吃晚饭的桌子上,在自家的屋子里,人们说话也得深思熟虑——教室里面也有这样的人,他们教小孩监视父母,该监听些什么,该向谁告发。

我三更半夜在这路边干什么呢?我应当躺在床上,盖着毯子,身旁放着一本毛边的旧书。这肯定是一场梦,肯定是。明天早晨,我会醒来,朝窗外望出去:人行道上没有那些阴沉着脸的俄国士兵在巡逻;没有坦克在我的城市里面耀武扬威,它们的炮塔活像责难的手指那样转动;没有断壁残垣,没有宵禁,没有俄国军队的运兵车在市场上迂回前进。这时,我听到爸爸和卡林在我身后讨论到了贾拉拉巴特的安排,持续了一根烟的时间。卡林一再向爸爸保证,他的兄弟有辆“很棒的、质量一流的”大卡车,到白沙瓦去可谓轻车熟路。“他闭上眼也能把你们送到那儿。”卡林说。我听见他跟爸爸说,他和他的兄弟认识把守关卡的俄国和阿富汗士兵,他们建立了一种“互惠互利”的关系。这不是梦。一架“米格”战斗机突然从头顶呼啸而过,仿佛在提醒这一切都是真的。卡林扔掉手里的香烟,从腰间掏出一把手枪,指向天空,做出射击的姿势,他朝那架米格吐口水,高声咒骂。

我想知道哈桑在哪里。跟着,不可避免地,我对着杂草丛吐出来,我的呕吐声和呻吟声被米格震耳欲聋的轰鸣淹没了。过了二十分钟,我们停在玛希帕的检查站。司机没熄火,跳下车去问候走上前来的声音。鞋子踏上沙砾。短促的低声交谈。火机打火的声音。“谢谢。”有人用俄语说。

又一声打火的火机声。有人大笑,一阵令人毛骨悚然的劈啪声让我跳起来。爸爸伸手按住我的大腿。发笑的那个男人哼起歌来,带着厚厚的俄国口音,含糊走调地唱着一首古老的阿富汗婚礼歌谣:

慢慢走,我心爱的月亮,慢慢走。

作品周边

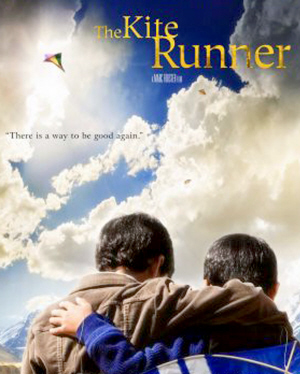

内容简介

12岁的阿富汗富家少爷阿米尔与仆人哈桑情同手足。然而,在一场风筝比赛后,发生了一件悲惨不堪的事,阿米尔为自己的懦弱感到自责和痛苦,逼走了哈桑,不久,自己也跟随父亲逃往美国。

成年后的阿米尔始终无法原谅自己当年对哈桑的背叛。为了赎罪,阿米尔再度踏上暌违二十多年的故乡,希望能为不幸的好友尽最后一点心力,却发现一个惊天谎言,儿时的噩梦再度重演,阿米尔该如何抉择?

故事如此残忍而又美丽,作者以温暖细腻的笔法勾勒人性的本质与救赎,读来令人荡气回肠。

作者简介

卡勒德·胡赛尼(Khaled Hosseini),1965年生于阿富汗喀布尔市,后随父亲迁往美国。胡赛尼毕业于加州大学圣地亚哥医学系,现居加州。“立志拂去蒙在阿富汗普通民众面孔的尘灰,将背后灵魂的悸动展示给世人。”著有小说《追风筝的人》(The Kite Runner,2003)、《灿烂千阳》(A Thousand Splendid Suns,2007)、《群山回唱》(And the Mountains Echoed,2013)。作品全球销量超过4000万册。2006年,因其作品巨大的国际影响力,胡赛尼获得联合国人道主义奖,并受邀担任联合国难民署亲善大使。

精选评论

热门评论

对友谊最大的误解,就是认为它是万能的(来自豆瓣网友:谢长留)

我时常幻想自己是来自未来的,这样,有一天我面对未来某一时刻的突然变化,就会更从容,面对陈年往事也会更慷慨。但,我更适合平庸,如寻常人一样琐碎繁杂的生活,对时间的细枝末节斤斤计较。

既然无法预知未来,那么人更多的开始依赖回忆,甚至靠那些零星琐碎的回忆支撑往后的日子,有些回忆很美好,有些回忆很心酸,有些回忆让人长大,有些回忆让人显得很无知,有些回忆慢慢泛黄,有些回忆仿佛就在昨天。有些故事也总是从儿时的回忆展开。

我对阿富汗以及周边连年征战的国家和他们的历史毫无兴趣,对我而言,那里的人民是可怜的,那里的政府是可悲的,所以当《追风筝的人》这个故事一点一点展现在我面前的时候,我并没准备好接受一个平静的,也曾春暖花开,羊肉串香飘整条街的画面,更没想到那里的孩子也可以无忧无虑的追逐风筝。

所以当身为少爷的阿米尔和他的仆人哈桑情同手足的画面一出现,所有读者不禁感叹,少年时的友谊是那么充满力量,干净而持久的。他们总是并肩而行,每当阿米尔被人欺负的时候,哈桑总是义无反顾的站出来保护,很多人说这是哈桑天生的奴性,这种观点我不赞同,我看见他们之间分明有一道友谊的光芒在闪耀。

当阿米尔问哈桑为什么确定自己一定会知道被切断绳线的风筝的掉落地的时候,哈桑肯定的对阿米尔说,我就是知道,然后反问,我什么时候骗过你。阿米尔轻声说,我怎么知道有没有骗过我。哈桑发誓,为了你,我宁可啃烂泥。阿米尔进一步确定,你真的会为我啃烂泥?哈桑坚定的说,我肯定,然后又说,但是你又怎么能忍心让我啃烂泥。所以读者心中所向往的也就是我们每个人心中那个潮湿的童年印象,总是和自己最亲密的伙伴,席地而坐,互相盟誓,发誓为对方,甘愿上刀山下火海。就如同哈桑洋溢着笑脸对阿米尔说的那样:为你,千千万万遍。

然而事实上却是这样的:他是主人,他是仆人;他是普什图,他是哈扎拉;他是逊尼派,他是什叶派,从他们出生的那一刻起,他们的命运就被这些他们所不能理解的标签所分隔开来,尽管他们是亲密无间的朋友,尽管他们事实上拥有同一位父亲。无论是平凡的阿米尔和哈桑,还是高高在上的查希尔国王或者卡尔扎伊,都不得不接受社会为他们预定的座位——阿米尔不再是阿米尔,哈桑也不再是哈桑,他们必须戴上社会分给他们的面具。

哈桑总是说“为你,千千万万遍”,而生性懦弱的阿米尔却选择沉默冷酷的逃避,这样的悲剧性结果并不单单是个性差异所造成的,在这些年少无知的孩子的潜意识里早已被灌输了相应于自身社会地位的“应该”与“不应该”,一个哈扎拉仆人理应为主人尽忠,而高贵的普什图少爷不值得为一个卑贱的哈扎拉仆人冒任何风险。

“阿米尔和哈桑,喀布尔的统治者”,这样的誓言只能是石榴树下的童话,“王子与贫儿”不可能成为兄弟,因为他们命中注定不平等。包括二十年后,阿米尔重返阿富汗的自我救赎行为,也只不过是在获知自己与哈桑的同父异母兄弟关系之后对身世的无奈认可,也就是说,他仍然没有证明自己已经找到了“重新成为好人的路”。

我们少年的时候,总是意气风发,三五结伴,促膝长谈。那是在我们其乐融融的环境中构建的虚拟场景,属于物理学讲究的理想状态,然而在残酷的现实面前,在微弱的友谊遇到挑战的时刻,只要有一方露出破绽,友谊的桥梁必然坍塌。

于是当阿米尔在看到哈桑被大一些的孩子欺负甚至猥亵的时候,他选择沉默和逃避;与此同时,哈桑却为了阿米尔的风筝坚定不动摇的和对手较量,对手残忍的揭示阿米尔和哈桑之间的主仆关系,哈桑大声反驳说两个人是朋友。躲在角落里不敢出现的阿米尔听到这句话不但没有一点激励也没有丝毫感动,他心底里的怯懦终于将他的灵魂吞噬,于是悲剧发生。

这就是我们对友谊最大的误解,认为它是万能的。

即使是存在这样的问题,《追风筝的人》也还是一本出色的小说。主和仆、贵族和贱民、朋友和兄弟,历史和现实,种种转变都被刻画得生动而细腻。放在历史的宏大背景下,更洞见人生和人性的复杂。

友谊和爱。

是在困难之中由弱变强的柔韧派还是在权衡利弊之中土崩瓦解的懦弱派。

谁敢真的站出来举起右手发誓,我从来没有辜负过任何一段纯粹的友谊,谁敢真的抬头挺胸说自己对朋友忠心不二。

我们总是太自信,对友谊误解,对自己的爱误解,对不可能的事信以为真。