(单词翻译:单击)

Kamakura Shirts owner Yoshio Sadasue opened a New York store on Madison Avenue. (Raymond Patrick)

日本人Yoshio Sadasue在纽约的麦迪逊大道上经营着这家“镰仓衬衫”

Acouple of years ago I found myself in a basement bar in Yoyogi, a central precinct of Tokyo, drinking cold Sapporo beers with big foamy heads while the salarymen next to me raised their glasses to a TV displaying a fuzzy, obviously bootlegged video of an old Bob Dylan concert. The name of the bar, My Back Pages, is the title of a Dylan song. Dylan is, in fact, the bar’s reason for being: Japanese fans come here to watch his concert videos, listen to his tapes and relive the ’60s in America, a time and place almost none of them witnessed firsthand. As I heard yet another version of "Mr. Tambourine Man" roaring over the speakers, with some drunk Japanese fans now singing along, I thought how strange this phenomenon was

几年前,我坐在位于东京中心区域,代代木的一家地下酒吧喝着满是泡沫的札幌啤酒,旁边的一个工薪族正对着一台播放着盗版,失真的鲍勃迪伦早期演唱会的电视举杯。这家酒吧的名字叫做“我的过去”,这是鲍勃迪伦一首歌的名字。事实上,鲍勃正是这家酒吧得以存在的原因:日本的粉丝们聚在这里看他的演唱会,听他的唱片,重温美国60年代的生活,一段他们并没有亲自体验过的生活。接着我听到有酒醉的日本粉丝跟着喇叭里喧闹的另外一个版本的“Mr. Tambourine Man”合唱,我觉得这个场景真的好奇怪。

The American presence in Japan now extends far beyond the fast-food franchises, chain stores and pop-culture offerings that are ubiquitous the world over. A long-standing obsession with things American has led not just to a bigger and better market for blockbuster movies or Budweiser, but also to some very rarefied versions of America to be found in today’s Japan. It has also made the exchange of Americana a two-way street: Earlier this year, Osaka-based Suntory, a Japanese conglomerate best known for its whiskey holdings, announced that it was buying Beam Inc., thus acquiring the iconic American bourbon brands Jim Beam and Maker’s Mark.

美国对日本的影响远远超过了遍布世界的快餐产业,连锁商店和流行文化层面。日本长时间对美国事物的痴迷不仅仅使他们的电影产业规模更大更好,更适合拍摄大制作电影或者生产百威啤酒,也使人们能够在这里找到一些更纯粹的美国。也使得对美国产业的交易变成了双向道:今年早些时候,总部位于大阪的著名的威士忌公司三得利,宣布他们收购了Beam Inc.。这样,他们也就获得了著名的美国波旁威士忌品牌:Jim Beam(沾边波旁威士忌)和Maker’s Mark。

In Japan, the ability to perfectly imitate—and even improve upon—the cocktails, cuisine and couture of foreign cultures isn’t limited to American products; there are spectacular French chefs and masterful Neapolitan pizzaioli who are actually Japanese. There’s something about the perspective of the Japanese that allows them to home in on the essential elements of foreign cultures and then perfectly recreate them at home. "What we see in Japan, in a wide range of pursuits, is a focus on mastery,"says Sarah Kovner, who teaches Japanese history at the University of Florida. "It's true in traditional arts, it’s true of young people who dress up in Harajuku, it’s true of restaurateurs all over Japan."It’s easy to dismiss Japanese re-creations of foreign cultures as faddish and derivative—just other versions of the way that, for example, the new American hipster ideal of Brooklyn is clumsily copied everywhere from Paris to Bangkok. But the best examples of Japanese Americana don’t just replicate our culture. They strike out, on their own, into levels of appreciation and refinement rarely found in America. They give us an opportunity to consider our culture as refracted through a foreign and clarifying prism.

日本人能够完美地模仿或者说改良外国的文化,如服装风格,烹饪技巧和鸡尾酒制作。不仅能模仿美国文化。很多技艺精湛的法国厨师和熟练的那不勒斯批萨师实际上是日本人。日本人有一种能认清外国文化的本质然后在日本本土把它复制出来的本事。 在佛罗里达学教日本历史的Sarah Kovner说 :“我们在日本看到,对技术的精通是人们普遍追求的,在传统艺术上人们如此,打扮成原宿娃娃的人如此,日本所有的餐馆也是如此”

日本人对外国文化的复制很容易被人认为他们只是因为喜爱而模仿罢了,就好像赶时髦的布鲁克林的新美国人肤浅地模仿人家巴黎和曼谷的文化一样,日本人只是另一个版本罢了。但是那些典型的日裔美国人模仿的可不只是我们的文化,他们(在没有导师的情况下)认识和改进事物的水平在美国可是很少见的。他们为我们提供了一个国外参照物或一面清晰镜子,让我们认识本身文化的不足之处。

A jacket at Workers reflects the line’s focus on recreating 20th-century American work clothing. (Raymond Patrick)

Workers公司的这件夹克反映了美国20世纪的工作服装。

(Raymond Patrick)

Into the fire Matsumoto Kozo’s flame-grilled burgers are Los Angeles-inspired. (Raymond Patrick)

在Matsumoto Kozo的火烤汉堡,是受到洛杉矶的启发而出现的。(Raymond Patrick)

Seiichiro Tatsumi drove America’s back roads to collect the old bourbons that line Rogin’s Tavern. (Raymond Patrick)

Seiichiro Tatsumi 在美国乡村小道上驱车收集年份较久远的波旁威士忌酒,图片上就是自己酒馆里所收集来的波旁威士忌。

(Raymond Patrick)

Into the fire Matsumoto Kozo’s flame-grilled burgers are Los Angeles-inspired. (Raymond Patrick)

在Matsumoto Kozo的火烤汉堡,是受到洛杉矶的启发而出现的。

Matsumoto Kozo named his Tokyo burger joint, 7025 Franklin Avenue, after the street address of the Hollywood hotel where he once lived. (Raymond Patrick)

Matsumoto Kozo以他曾经住过的好莱坞酒店所在的街道地址来命名这家位于东京的汉堡店。

Kamakura’s Three Hundred Club Shirt boasts 20 to 22 stitches per inch on a single needle seam. (Raymond Patrick)

Kamakura 的“三百俱乐部衬衫”每一英寸的缝合处都要缝上20到22针。

Owner Seiichiro Tatsumi enjoys the bourbon and cigars at his bar, Rogin’s Tavern. (Raymond Patrick)

Seiichiro Tatsumi在他的Rogin酒馆里面享受波旁酒和雪茄。

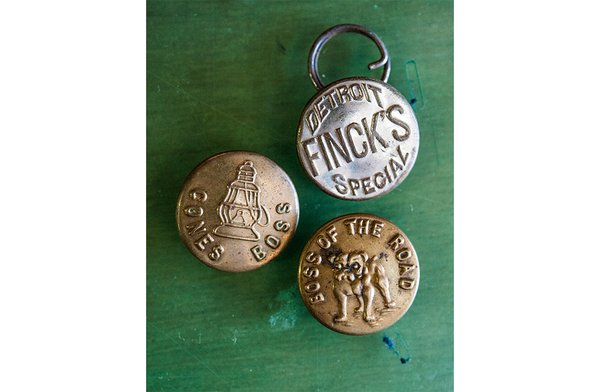

A collection of vintage buttons adds to the authenticity of the American work wear at Workers. (Raymond Patrick)

许多老式纽扣增加了美国工人服装的真实性。

Bourbon

波旁威士忌酒

When I headed to Osaka a few months ago, my friend Nick Coldicott, who lives in Tokyo, urged me to visit what he contends is the best bourbon bar in the world: Rogin’s Tavern. Knowing Nick’s command of the spirits universe, I take a commuter train out to Moriguchi, an obscure little town about half an hour from the center of Osaka. When I emerge from the station I can see a neon light spelling "Rogin's" in English. Inside it is dim, with a long wooden bar backed by hundreds of bottles. American jazz comes from an ancient-looking jukebox in the rear.

当我几个月前往大阪时,我住在东京的朋友Nick Coldicott敦促我去参观他认为是世界上最好的波旁威士忌酒吧:Rogin’s Tavern(罗金的酒馆)。我知道Nick对酒精非常的了解,于是我乘坐了一列通勤列车前Moriguchi ,一个距离大阪市中心大约半小时车程的无名小镇。当我达到车站时我可以看到一个霓虹灯拼写的英文“Rogin’s”。里面很昏暗,里面有一个很长的吧台,后面排列着几百瓶酒。一个古老的点唱机里传来了美国爵士乐。

Nearly every bottle is bourbon, though there is a smattering of rye and sour mash. I can see bottles from the 1800s next to obscure export bottlings of Jim Beam next to standard-issue Jack Daniel’s. Seiichiro Tatsumi, an older man dressed elegantly in bartender’s attire, emerges from the shadows and says hello in English. I tell him I am a friend of Nick’s, and he reaches for a bottle nestled behind the register. "You want to try a 1904?" he asks.

几乎每瓶都是波旁,虽然有少数的黑麦和酸麦芽浆。我可以看到很多19世纪年份的酒瓶子,还有用于出口的占边·波本威士忌,尽管瓶身略显模糊,还有标准的杰克丹尼尔。(占边波本威士忌:始于1795年,历经占边家族七代酿酒师,始终保持产品的最高品质并成为全世界和全美销量第一的波本威士忌 。 杰克·丹尼 世界十大名酒之一 1866年诞生于美国田纳西州莲芝堡,单瓶销量多年来高踞全球美国威士忌之首。是美国最古老的注册酒厂) Seiichiro Tatsumi ,一个年长的穿着得体的酒保服装男士,从阴影里浮现出来用英语说“hello”,我告诉他我是Nick的朋友,于是他拿了一瓶酒过来。“你想尝试一下1904年的佳酿吗”?他问道。

He tenderly unscrews the top and pours a shot for me and another for himself. I take a sip. It is a brand I’ve never heard of, once made, Tatsumi says, especially for a hotel in Kentucky. It is highly alcoholic but silky smooth. Unlike wine or vintage port, bourbon is not supposed to change much in the bottle over time. And so I think of this as a chance to taste the past and experience, almost exactly, what drinkers were sipping a hundred years ago.

他轻轻地旋开瓶盖,他倒了一杯给我,给自己也倒了一杯。我小品一口,这个品牌的酒我从来没有喝过,据他说之前这是为肯塔基州的一家饭店专门制作的。 度数很高但感觉爽滑。不像葡萄酒或者年份波特,波旁威士忌不会因时间的推移而产生太多变化。所以我觉得这是品味过去和历史的大好机会,因为我现在所喝的和100年前人们所喝的没啥两样啊!

"I tasted my first bourbon in the basement bar of the Rihga Royal Hotel, a famous old place in Osaka," Tatsumi says. "Then I spent years reading everything I could about bourbon at the American cultural center. I sent letters to Kentucky and Tennessee trying to set up visits to the distilleries. I even asked for help at the American consulate. And then I finally got to visit in 1984. I fell in love with America then. I’ve been back a hundred times since. I now own a house in Lexington, and I’ve even been named a colonel in Kentucky."

辰巳说:“我在大阪的一家驰名老店--丽嘉皇家酒店的地下酒庄里第一次尝到了波旁威士忌,然后我花了几年时间在美国文化中心里学习有关波旁威士忌的所有知识。我寄信往肯塔基州和田纳西州希望能去拜访那里的(波旁)造酒厂,我甚至求助于美国领事馆。结果如我所愿我在1984年得到了邀请,从此我就爱上了美国。那之后我来回日本美国之间已有上百次,我现在在列克星敦有一处房产,甚至被任命为肯塔基州的一名上校。”

I ask him how he found all these old bottles of bourbon. "I drive across America, only on the back roads and especially at night, when you can see the lit-up liquor-store signs in the distance," he says. “I stop at every place I pass, and I don’t just look on the shelves: I ask the clerk to comb the cellar and check the storeroom for anything old. I can’t tell you how many cases of ancient bottles I’ve found that way. I’ll try any bourbon once, and if I like it I buy more."

我向他请教如何收集到这么多的陈年波旁酒,他回答说:“我曾经驾车穿越了美国,都是通过乡间小路而且挑的都是晚上,因为那时候你能看到远处的酒馆小店的招牌在发光。我在每处小店都会停留一下而且我不只是看货架,我会请求店员清查地窖并找出所有存着的旧货,我无法向你形容用这种方法我找到了多少波旁陈酿,每一种波旁我都会品尝一下,只要我喜欢我就买下来。”

The next day I visit another bourbon bar in Osaka, Tonen (meaning "decade"), in a downtown neighborhood where salarymen go drinking. This is the bar of the bourbon master from whom Tatsumi originally learned. A pack of businesspeople parade into the place and one asks for one of the most expensive and rare contemporary bourbons around, Pappy Van Winkle, a bottle of which can cost more than $1,000. The bartender makes a big show of pouring this cultish favorite, laying the snifter down horizontally and swirling the bourbon inside it before presenting it to the man who ordered it, obviously the boss of the group. Then he comes over and we talk about his old bottles, and I see a glint in his eye. For someone in Kentucky or Tennessee it might be called nostalgia, but can you be nostalgic for a time and place you never knew? These two Japanese bourbon temples represent a bold act of imagination.

第二天我来到大阪的另一家位于下城区的工薪阶层光顾的波旁酒馆,托恩(意思是十年)酒馆。该酒馆是Tatsumi最早开始知道的一家波旁专业酒馆。当天一群商务人士涌入这个地方,有人点了一杯最为昂贵并且少见的现代波旁酒——派比 范温克威士忌,一瓶1000多美金。服务员在倒这种令人痴迷的酒时,展示了精湛技艺,他水平地摆好酒杯,令波旁酒在杯中不断打转,然后展示在客人面前。很明显,这个人是这一群人的老板。随后他走过来,我们聊到他买的这瓶老酒,我看到他目光一闪,仿佛某些肯塔基或田纳西人怀有的思乡病一般。但是你会对一个你并不了解的时代和地点产生乡愁的情绪吗?这两个日本波旁酒馆呈现出了大胆的想象。

Back in the States I phone up bourbon bars from Manhattan to Louisville, and their responses are all the same: We have old-style bourbons, but not anything old. And then I call Keith Biesack, the beverage director at what may be New York City’s best bourbon bar, Char No. 4, and I ask why no one in America stocks anything really old. "Until very recently people didn’t think they wanted to drink anything but newly bottled bourbon," he says. “The idea that this was a drink whose past you’d want to discover through old bottles, that’s a very new idea."

回到美国,从曼哈顿到路易斯维尔我给很多波旁酒吧都打了电话,他们的回应都相同:我们有老式的波旁酒,但都不久远。随后,我又给毕塞科打了电话,他是纽约市可能最好的波旁酒吧——查理四号的酒类销售总监。我问到他为何美国酒吧中都没有真正的老酒。他说:“因为一直以来人们都想喝新装的酒,而通过喝酒来探索过去的历史,这样的想法才刚刚出现而已。”

Not in Japan, I think, and I imagine Tatsumi 25 years ago roaring across the small roads of the American South and discovering bottles that only he knew to treasure.

但日本可不这样,而且我能够想象25年前Tatsumi 呼啸着穿过美国南部的小路,只为发现值得珍藏的陈年老酒时的样子。

Jazz

爵士音乐

A few years ago a friend took me to Samurai, a jazz bar in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district whose owner, a haiku poet, stood behind the bar surrounded by thousands of maneki neko—smiling, waving cat figurines. He had a primitive video camera trained on the sleeve of the record album he was playing, and he projected that image onto the wall. Samurai had its own quirks, but it wasn’t an unusual type of place: The jazz bar and its cousin, the jazz kissaten, a coffee shop focused on jazz, are shrines to recorded music, dreamlands for high-fidelity obsessives. They offer a kind of jazz experience based on pure appreciation of the act of listening.

几年前一个朋友带我去了 Samurai——一家位于东京新宿区的爵士酒吧,酒吧老板是一位俳句诗人。他站在吧台后面,周围是数以千计的招财猫——微笑着,挥动手臂。他用一个老式的放映机播放胶片,把影像投射到墙上。这家店有自己的风格,但在日本并非少见,比如爵士吧和爵士咖啡馆——专注于爵士乐的咖啡店,热衷于播放音乐磁带,以成为高保真乐迷们的梦想天堂,通过纯粹的倾听来享受爵士乐所带来的快乐。

In Tokyo I track down James Catchpole, an American expat and jazz expert who goes by the very Japanese-sounding nickname of Mr. OK Jazz, to understand what’s happening right now to Japanese jazz culture. "When these kissa started back in the '50s and '60s, Tokyo apartments were too small to play music in," Catchpole says. "Imported records were really expensive. Jazz kissa were the only places in the city where fans could listen to the music they loved." The coffee shops became hideaways where jazz lovers could relax, hear new records and learn about trends like free jazz from others who knew the music well. In the ’60s, when jazz was allied with Japanese university counterculture, jazz kissa became organizing centers for the student protests that rocked Japan. But of course Japanese people no longer need to visit a bar or café to listen to recorded jazz. "Are jazz kissa going to survive?" I ask Catchpole.

在东京,为了理解现在日本的爵士文化,我找到了凯奇波尔。他是一位美国移民和爵士乐专家,周围追捧他的日本人送给他一个绰号为ok爵士先生。“当这种爵士咖啡馆在5、60年代刚刚兴起时,东京的房子还太小,所以不足以播放音乐。”他说道,“并且进口的磁碟非常昂贵。所以城市里的乐迷们只有在这种咖啡馆里才能听到自己喜欢的音乐。”这样的咖啡店成为爵士迷们放松心情的桃花源,来到这里欣赏新的乐曲,从深谙爵士乐的人那里了解像自由爵士乐一类的流行风尚。在60年代,当爵士乐与日本大学的反主流文化结盟后,爵士咖啡吧成为学生们组织抗议的根据地。但当然,日本人现在不再需要去酒吧或咖啡馆来欣赏磁带爵士乐了。我问凯奇波尔“那么爵士咖啡吧还会继续存在吗?”

"Go to Kissa Sakaiki and find out," he says.

“去sakaiki咖啡吧找答案吧”他说。

Tokyo's tiny cafés, bars and restaurants are notoriously difficult to locate. Even with a GPS-equipped iPhone, a print atlas and the help of police guarding a nearby embassy, I spend half an hour wandering the back streets of Yotsuya, a residential Tokyo neighborhood not far from Shinjuku, before I turn the corner and see the discreet sign for Sakaiki.

东京的微型咖啡店、酒吧和餐馆特别难找。即使用GPS定位功能的iphone,一张地图册,并且在附近大使馆保安的帮助下,我还是在临近新宿地区的yotsuya居民区的小街里转了半个小时,转过一个街角才发现隐秘的sakaiki店铺标志。

What makes places like Sakaiki or the Bob Dylan bar survive and sometimes prosper is the fragmentation of bar, café and restaurant culture in Tokyo. An eight-seat pub stands out in New York as supremely small, yet in Tokyo there are at least three nightlife neighborhoods consisting almost entirely of eight-seat bars. You don’t need many fans of whatever it is you’re into to support a bar, café or restaurant devoted to that obsession.

像sakaiki或者鲍勃迪伦酒吧做之所以能够生存甚至繁荣起来,主要应归因于东京破碎的酒吧、咖啡馆以及小餐馆文化。在纽约一个八个座位的酒吧会显得极其狭小,而在东京至少三个夜生活地区完全都是由这类型酒吧组成。无论如何,你并不需要太多乐迷来支撑这样专门的酒吧、咖啡厅或者餐馆。

When I enter Sakaiki, owner Fumito Fukuchi, wearing a gray newsboy cap turned backward, waves me to the bar. Seated next to me is a Swedish free-jazz clarinetist speaking English to a group of Japanese. I tell Fukuchi that Mr. OK Jazz sent me. He nods a welcome and serves me a cold beer. The place is small, warm and gently lit, with a green-shaded banker’s lamp shining on the album cover of the record he’s playing. I ask Fukuchi how he came to run Sakaiki.

当我进入sakaiki,带着灰色报童帽的老板fukuchi便向我招手,带我进去。坐在我旁边的是一个瑞典的自由爵士乐吹奏者,正在操着英语与一群日本人交谈。我告诉fukuchi是ok爵士先生叫我来的。他点头表示欢迎,给了我一杯冰镇啤酒。这地方很小,但很暖和。一盏墨绿色的银行家台灯在唱片封面上闪着柔和的光。我问fukuchi为什么要经营这这家sakaiki。

"I was a salaryman working in IT until 2007," he tells me, as he cleans, inspects and preps the next record in his rotation. "Jazz kissa were my hobby," he says, leading me to a coffee table covered in matchboxes from the jazz kissa of Tokyo. He picks up a matchbook that reads, "Eagle." "This is the first one I ever visited. It’s right here in Yotsuya. I read the owner’s book about jazz when I was a teenager in Hokkaido. As soon as I came to Tokyo, I headed for Eagle." Many of the matchbooks Fukuchi flips through are from jazz kissa that have long been closed. And all the other jazz kissa he knows of in Tokyo, he tells me, are run by men a decade or two older than he is—and he's 41.

“直到2007年之前我都是一个在IT行业工作的工薪族,”他一边清理、检查并且为下次循环记录做准备,一边和我说。“爵士咖啡馆是我的爱好”他边说边领着我到了放满了来自于东京爵士咖啡馆火柴盒的茶几边。他拾起一个火柴盒并读到“Eagle,这是我曾经去过的第一个爵士咖啡馆,它就在这儿,四谷。当我在北海道,还是个孩子的时候,我读了那间咖啡馆主人有关爵士的书籍。我一到东京,就直奔Eagle而去。”Fukuchi收集的许多火柴盒都来自于已经关闭许久了的爵士咖啡馆。他告诉我说,他所知道的在东京的所有其他咖啡馆都由比他大十几二十几的人在运营着——而他已经41岁了。

The obvious question is why go out of your way to hear recorded music with other people when technology has made it easy to listen alone? The answer comes to me as I look around the room at the people brought together by the music Sakaiki has collected: International jazz musicians, local workers and jazz fans from all over the city are here because they appreciate the act of listening to a record together. It’s a pleasure that anyone who grew up before the era of the Walkman and iTunes can appreciate. What’s uncertain is whether the next generation will cherish the same experience.

最显而易见的问题是为什么当现在技术已经使你很容易能找到想听的音乐的时候,你还需要和别人一块去听录制音乐?当我环顾房间,看见因为Sakaiki收集的音乐而聚集在一起的是什么类型的人时,答案就不言自明了:是国际爵士音乐家,当地的工人以及来自于这个城市各个地方的爵士粉丝们,他们来到这里是因为他们欣赏这种聚在一起听录制音乐的行为。很高兴在这个拥有Walkman和iTunes的时代之前长大的人能够欣赏这样的行为。但我并不确定我们的下一代是否将会珍惜这样的经历。

Work wear

工装

Takashi Tateno keeps an office in a simple studio above his wife’s hairdressing salon on the outskirts of Okayama, a medium-sized city in central Japan. In fashion circles, Okayama is famous for one thing: making the world’s best denim, using looms that date back to the 1950s. But Tateno isn’t a denim head. His brand, called Workers, adapts all sorts of American work wear from the 1900s to the ’60s—railroad jackets, canvas dusters, flannel shirts, double-kneed pants. Moreover, he’s obsessed by the American workers who manufactured these garments in their heyday, and the skills, techniques and tools used to produce such high-quality clothing on an industrial scale.

冈山是日本中部的一个中等城市。Tateno简陋的办公室坐落在在市郊,在他妻子经营的理发店上面。在时尚圈中,冈山以加工世界上最好的工装而著称,使用织布机的历史可以追溯到50年代。但Tateno的企业并非工装方面的领头羊。他创建了名为工人的工装品牌,产品由美国在1900年开始直至60年代的所有工装改进而来,包括:铁路工人的防护服、三防布、法兰绒衬衫、膝部加厚的工装裤。此外,他还一直着迷于在美国全盛时代生产这些工装的工人们,他们的技术、技能以及在如此高质量工装的工业化生产中所使用工具。

Before he hatched the idea of his own collection, Tateno spent years making clothes himself and working in a factory. At the same time, he launched a Japanese-language website that was absolutely alone in its single-minded pursuit of knowledge about the plans, patterns and procedures that old American work-wear manufacturers used to make their garments under such labels as Crown, W.M. Finck & Co. and Can’t Bust ’Em. Tateno journeyed to the United States multiple times to sift through archives and contact heirs to now-defunct clothing manufacturers to see if they had information about their ancestors’ businesses, and to buy up examples of the old clothes he loved so he could dissect their construction.

在总结出自己的理念之前,Tateno花费数年时间亲手制作服装并且在工厂参与工作。与此同时,他还创建了一个日语网站,完全一门心思的学习旧时美国工装制造商的设计、式样和加工工艺方面的知识。这些美国工厂创造了包括:皇冠、芬克以及康巴斯特在内的优秀品牌。Tateno来到美国花费大量时间查阅档案,联系已经落败了的旧时工厂的继承人,了解他们前辈在工厂经营方面的信息,并且还购买了他喜欢的那些老款服装样服,以剖析服装结构。

Tateno ushers me into his upstairs space. One room is filled with all kinds of clothing, everything from the work wear he collects to contemporary Italian jackets by Boglioli. There is also machinery, including an ancient riveting machine, plus old sewing-machine accessories that Tateno purchases so the factories he hires to produce his collection can make things to the exact specifications of, say, 1924 or 1942, with the same tools in use back then.

Tateno带我来到他楼上的房间。有一个屋子里堆满了各式各样的工装,从他收集的各式防护服到由贝格里尼设计的现代意大利夹克衫。还有他购买的老式缝纫机的零件,据他所说,1924年或42年购买了这些零件,目的是为了当时能够使用与美国同样的工具,生产规格完全一致的工装。

"When I learned to sew and tried to make these garments myself, I began to realize just how intricate the work was, what kind of tremendous skill level was required to turn out such huge quantities of high-quality garments," Tateno says. "These were produced at a time when American workers were the most knowledgeable and skilled in the world."

“当我学习到缝纫,并且尝试自己制作这些防护服时,才意识到这项工作是如此精细,需要极高的技能才能生产出大批如此高质量的工装。”Tateno说“生产这些服装的美国工人是当时全世界知识和技能水平最高的。”

Though the kind of skilled manufacturing he admired in these garments had largely disappeared in the United States—a consequence of apparel production moving abroad and garment workers no longer finding work—he saw older Japanese people around him in Okayama with high-level sewing skills. And so he realized that if he could unearth the manufacturing secrets behind these old garments, he could make them in Okayama—and perhaps make them even better than the originals.

由于美国将服装这类产品的生产转移海外,服装厂的工人们纷纷失业,尽管他所羡慕的这些技术熟练的美国服装企业中大部分已经倒闭,但他在冈山看到自己周边还有很多年长的日本人仍具备高超的缝纫技艺。因此他感到如果他能够揭开在这些老式防护服背后的技术机密。他便能够在冈山制造这些防护服,甚至或许比原来的更好。

The cult of the artisan is ensconced in contemporary urban American culture. This is the ideal of a person who can handcraft a pair of jeans or a necktie, conscious of the most minute details of fabric, workmanship and authenticity. The era Tateno’s clothing harks back to is not the age of the lone artisan laboring over a single creation, though; it’s the era of packed factories in Pennsylvania, Virginia and California churning out thousands and thousands of high-quality garments at a reasonable price, all because of the workers’ skill. The irony is that this ideal of the American worker, which sounds like something lifted from old-school union advertising copy, can be hard to find in America today.

对熟练技工的狂热已经躺倒美国现代城市文化的历史中。工人专注于纺织材料、加工技艺以及关乎可靠性的每个细节,手工打造一条牛仔裤或领结的情景已只存在理想之中。 然而Tateno的服装所处的已不是单个工匠独自创造的年代,而是宾夕法尼亚、弗吉尼亚和加利福尼亚的工厂中以低廉的价格成批出产千千万万套高质量服装的时候。所有的一切都因为工人的技艺问题。具有讽刺意味的是美国工人的那种似乎由老式学堂演化而来的理想,在今天的美国已经难觅踪影。

Burgers

汉堡

For years Matsumoto Kozo owned and ran a restaurant in Tokyo, cooking yoshoku, which is the Japanese word for the Western food that came to Japan over 100 years ago. Then Kozo got a chance to go to America and manage a couple of restaurants for Japanese investors. He moved to Los Angeles and lived in a strange little hotel called the Magic Castle, just a couple of blocks uphill from Hollywood’s tourist strip.

多年来,kozo在东京拥有并经营着一家餐馆,主营yoshoku,这是日语中对100多年前引入日本的西餐的称谓。之前kozo有机会来到美国,为日本投资者打理两家餐馆。他来到洛杉矶,住在名为魔法城堡的小旅馆,从好莱坞景区上坡,到旅馆只有两条街区。

One day there was a big barbecue party down by the pool. This was the early 1980s, and the glamorous, glittering, feline cast and crew of Cats were bunking at the Magic Castle, too. It was their day off. When they saw Kozo and his family come out of their unit, they insisted that he join the party. They were grilling burgers over an open flame. But it was 3 in the afternoon and Kozo had already eaten. So he asked if he could wrap up the burger to enjoy later. No way, the Cats said, you can’t save a burger like that. You’ve got to eat it here and now. It wasn’t his first hamburger—he’d eaten one before at McDonald’s in Tokyo and at MOS Burger, a Japanese chain. But this flame-grilled, all-beef patty was something categorically different.

有一天,在游泳池边组织了一场盛大的烧烤派对。当时是80年代初,当时歌剧《猫》的剧组人员正在参加派对。当看到kozo和家人走出房门,他们坚持kozo加入晚会。他们在篝火上烤汉堡。当时是下午三点钟,kozo已经吃了午餐。因此,他问是否允许他把汉堡打包稍后再吃。他们说不可以,你不能这样子保存汉堡,必须及时吃掉。这并不是他第一次吃汉堡,他之前在东京的麦当劳以及日本连锁店摩斯汉堡里都吃过,但这次的火焰烧烤、全牛汉堡完全不一样。

When he moved back to Japan a few years later, Kozo thought back to that afternoon at the Magic Castle. He found a place in a residential Tokyo district called Gotanda. It was big enough for a restaurant and a little garden. This was 1990. There were a handful of burger joints already in Japan, but they served burgers as a fast-food snack. (Now there are around 2,000 independent Japanese-run burger places, Kozo says.) He built a real restaurant with a station for grilling burgers in the middle. He enlisted the help of a friend to design a menu that was suitably American, printed on brown paper, with a logo that featured a chef holding a spatula and tossing a plate. He called it 7025 Franklin Avenue, the street address of the Magic Castle Hotel.

当几年后他回到日本,kozo想到了在魔法城堡的那个下午。他在东京的一个名为gotanda 的聚居区找到了一个地方,足够开个餐馆和一个小花园。那是1990年,日本已经有了几家汉堡连锁店,但他们只是把汉堡作为快餐来销售。(kozo说,现在日本已经有2000多家独立的汉堡店。)他开了一个餐馆,屋子中间有一个台子用于烤汉堡。他列出菜谱,一位朋友帮他设计了美国化的菜单。菜单印在棕色纸上,上面有个标识图案,显示一个厨师拿着铲子,摆弄着一个盘子。他把餐馆命名为富兰克林大道7025号,也就是魔法城堡在美国的地址。

Kozo still mans the grill nearly every day, though he does have a Nepalese chef who has been working by his side for years, and whose daughter cashiers and waits on tables. The cheeseburger I order, made from Australian beef, is simple and superior. The char is unmistakable, and the meat has a consistency and flavor, so familiar at home, that I have never seen replicated abroad.

虽然一个尼泊尔大厨已经在他身边工作了许多年,但kozo仍旧每天做着烧烤,大厨的女儿作为收银员和服务员。我点了一份干酪汉堡,由澳洲牛肉制成,简单却美味。烤的恰到火候,牛肉均匀,味道鲜美,像自己家里的味道一样。在国外我从未品尝过类似的汉堡。

I ask Kozo whether he’s been back to the Magic Castle or to the States since returning here in 1985. "I've never been back," he says, tears forming in his eyes. "I always wanted to go, but I haven't made it yet. Which is kind of amazing, since this whole business is thanks to America. This is what I found in America and wanted to bring back to Japan."

我问kozo1985年回国后,是否再回过魔法城堡或美国。“我再也没回去过”他眼中泛着泪花说。“我总想回去,但都没成行。这有点让人惊讶,因为我的所有生意都要归功于美国,我在美国发现了这种做法并且带到日本。”

Shirts

衬衫

A Japanese company called Kama-kura Shirts opened on Madison Avenue in Manhattan in 2012, just blocks from Brooks Brothers and J. Press, the icons of American preppy wear, what cognoscenti call "trad"and the Japanese call "Ivy style." (Never mind that Brooks Brothers is owned by the Italians, J. Press by the Japanese.) I track down Kamakura’s founder, Yoshio Sadasue, at his headquarters in Tokyo, above a Kamakura Shirts in Ebisu. He is sharply dressed in his trademark style: a button-down shirt with a distinctive collar roll, what Sadasue considers the essential feature of his design. I ask why a Japanese manufacturer opened a New York store to sell American-style shirts to Americans.

一家名为kamakura的生产衬衫的日本公司2012年在曼哈顿的麦迪逊广场开业了。距离布鲁克斯兄弟和普莱斯店面只有几个街区之远。这两家公司是美国生产毕业生礼服的代表性企业,行家们把这种服装称为“传统式”,而日本人称作“艾维式”。(不用说布鲁克斯兄弟公司老板是意大利人,而普莱斯的老板是日本人。)我在位于东京ebisu的公司总部找到了kamakura的创始人,sadasue。他笔挺地穿着该公司标志性产品,领尖带有纽扣的衬衫以及独特的领口设计——sadasue认为这是该公司产品的重要特征。我问到为何日本公司会在纽约开店,售卖美式的衬衫给美国人。

"This style originated in America, of course," Sadasue says. "But there was a period of time when Americans forgot their own style."

他说“这种式样确实产生于美国,但美国人忘记了他们自己的这种样式已经很久了。”

Kamakura Shirts are made in Japan. Sadasue doesn’t sell them through department stores or other retailers because he wants to keep prices low and profits high, particularly for the independent factories that produce for him. As with Tateno at Workers, there is an undercurrent of respect for what those factories do and a strong desire to make sure that they can keep doing it in Japan.

kamakura衬衫在日本制造。sadasue并没有通过百货商店或者其他零售商出售,因为他想保持低价,获取高利润,特别是要让为他们生产产品的工厂获得低价和高利润。就像Workers品牌创始人Tateno一样,这些企业家对日本工厂总是充满敬意,并且强烈的希望这些日本工厂可以继续坚持下去。

This movement of American style across the ocean to Japan and back to America with a Japanese twist is happening more frequently. The most famous example is probably Daiki Suzuki, who was design director for the quintessentially American brand Woolrich Woolen Mills and now produces his own menswear line—Engineered Garments, a Japanese-run American brand that manufactures its unique take on vintage Americana in New York and sells it in both Japan and the U.S. One of his former employees, Shinya Hasegawa, now has a Brooklyn-based line called Battenwear that offers his interpretation of American outdoor wear from the ’60s to the ’80s. I had never encountered the brand in the States, but I found it in Kyoto.

美国风格漂洋过海来到日本,再经过日本改造后返回美国,这样的情景屡见不鲜。最著名的例子或许是suzki,他曾是经典的美国品牌Wolrich woolen mills的总设计师,目前建立了自己的男装企业——工程用服装公司——这是在纽约的一个日本人经营的美国企业,产品采用独特的老款美国设计,向日本和美国出售。曾经的职员hasegawa现在也在布鲁克林拥有了一家名为battenwear的工厂,对60到80年代的美国户外服装进行自己的诠释和生产。我从未在美国见过这个品牌,但我在东京发现了它。

Part of what’s going on is simply the globalization of taste, culture, cuisine and the way that, in the modern world, you can get almost anything everywhere. But Japanese Americana is more than that. There’s a special way that the Japanese sensibility has focused on what is great, distinctive and worthy of protection in American culture, even when Americans have not realized the same thing. It isn’t a passing fad. It’s a long-standing part of Japanese culture, and, come to think of it, as more Americans are exposed to U.S. products revived or reinterpreted by Japanese designers, the aesthetic is becoming part of American culture, too. If you ever wonder which of the reigning American tastes, sounds, designs or styles will last into the future, there’s no better place to answer that question than in the stores and restaurants, the bars and studios of Japan. They often know us better than we know ourselves.

在现代,品味,文化,美食和烹饪方式正在发生全球化, 你几乎可以在任何地方获得任何东西。但是日本人对美国文化的应用并非如此而已。当美国人自身还未察觉的时候,日本人却能凭借敏感的审美找到美国文化中那些好的,独特的,有保护价值的精华。这并非是他们一时的兴趣,而是一种长久以来就存在的日本文化。而且,想想看,当更多美国人接触到了被日本设计师们复兴并重新诠释的的美国商品时,这种日本的审美也逐渐变成了美国文化的一部分。如果你还想知道哪些地方将会在未来引领美国人的味觉、听觉、设计以及风格样式的潮流, 那最好的答案就是日本的商店、餐馆、酒吧和工作室,因为他们通常比我们更加了解我们自己。