(单词翻译:单击)

Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending is a good novel. We know it's a good novel because lots of people like it, and because it won the Man Booker, one of the biggest prizes in English-language literature. But here’s the funny thing. After the book won the prize, people didn't like it as much! Its rating on the site Goodreads took a sudden plunge. And it wasn't the only book to suffer that fate. A recent paper by sociologists Balázs Kovács and Amanda J. Sharkey studied a group of 32 English-language novels that won major literary awards. After the prize, their ratings on Goodreads dropped from an average of just under 4 to about 3.75. A group of comparably rated novels that were short-listed for prizes, but didn't win, showed no such diminution.

朱利安·巴恩斯的小说The Sense of an Ending不错。很多人都喜欢这部小说,并且它还获得了布克奖——英语文学的重量级奖项之一。但是奇怪的事儿来了。在获奖之后,人们没有从前那么喜欢这部小说了。它在Goodreads上的排名骤然下滑,而且它并不是唯一遭此厄运的小说。最近社会学家巴拉兹·卡瓦茨和阿曼达·J·莎克里发表了一篇论文,其中研究了一组共32部英语小说,它们都曾获得过重要的文学奖项。在获奖之后,它们在Goodreads上的排名平均下滑3.75到4个位次。另外一组研究对象则是入围但是最终并未获奖的小说,它们跟获奖小说的水平相当,但是却未出现如此现象。

When a book wins a Booker, that ought to make us think it’s good. Every sociologist—OK, every human being over the age of 12—knows we like things more when we hear that other people like them. So what explains the Booker backlash?

如果一本书能够获得布克奖,我们会理所当然的认为它是本好书。每一位社会学家,好吧,每一个12岁以上的人,都知道如果我们听说有其他人也跟我们一样喜欢一样东西,那我们会更加喜欢它。那又如何来解释“布克反弹”现象呢?

At least in part, it’s a quirk of statistics called Berkson's fallacy. If you know one thing about correlation, it’s that correlation is not the same as causation. Two variables, like height and math scores in school kids, may be correlated, even though being good at math doesn’t make you taller, or vice versa. What’s going on is that older kids are both taller and better at math. Correlation can arise from a common cause that drives both variables in the same direction.

从某种程度来说,它是一种被称之为伯克逊谬误的统计失真。如果你对相关性略知一二,你会知道相关并不代表因果关系。比如两个变量,学生的身高和数学成绩,它们可能具有相关性。虽然数学成绩好并不能让你长高,同样的,你再长得高点,也不能提高你的数学成绩。事实是,年龄大一点的孩子通常个子高一些,同时他们的数学成绩也会好一些。基于一个共同的原因,使得两个变量朝着相同的方向发展,由此两者之间产生了相关性。

But that's not the only way misleading correlations can pop up. Joseph Berkson, the longtime head of the medical statistics division at the Mayo Clinic, observed in 1938 that correlations can also arise from a common effect. Berkson's research was about medical data in hospitals, but it’s easier to explain the phenomenon in terms of the Great Square of Men.

但是这并不是误导相关产生的唯一原因。约瑟夫·伯克逊,长期担任Mayo诊所的医学统计部领导,他在1938年发现共同的影响也可以导致相关性。伯克逊的研究是基于医院的医学数据,但是我们可以通过“大方块中的男人”这个例子,来更容易的解释这个现象。

Suppose you’re a person who dates men. You may have noticed that, among the men in your dating pool, the handsome ones tend not to be nice, and the nice ones tend not to be handsome. Is that because having a symmetrical face makes you cruel? Does it mean that being nice to people makes you ugly? Well, it could be. But it doesn't have to be.

假设你在和男人约会。你可能会注意到,在你的候选人员中,那些帅哥的脾气更加不好,而那些友好的男人又往往更丑些。这是否意味着对人友好会把人变丑?好吧,也许是的。不过不是非得这样。

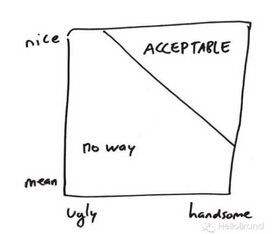

Behold the Great Square of Men. (And I'd like to note that you can find more stunning hand-drawn illustrations just like this one in How Not to Be Wrong.)

让我们回到“大方块中的男人”。(而且我想提醒你,在How Not to Be Wrong.中你会找到比下图更惊人的手绘插图)

Now, let’s take as a working hypothesis that men are in fact equidistributed all over this square. In particular, there are nice handsome ones, nice ugly ones, mean handsome ones, and mean ugly ones, in roughly equal numbers.

现在,让我们做一个有效的假设,即方块中的男人实际上是等分布的。更具体点说,我们把这些男人分为4类,既友好又长得帅的,友好但是长得丑的,不友好但长得帅的和不友好又长得丑的,每一类的人数都差不多。

But niceness and handsomeness have a common effect: They put these men in the group of people that you notice. Be honest—the mean uglies are the ones you never even consider. So inside the Great Square is a Smaller Triangle of Acceptable Men:

但是友好和帅气具有一个共同的效应:只有这些人你才会注意到。说实话,那些脾气又臭长得又丑的男人根本不在你的考虑范围之内。因此在这个大方块中,只有一个小三角才是你的选择范围。

Now the source of the phenomenon is clear. The handsomest men in your triangle, over on the far right, run the gamut of personalities, from kindest to (almost) cruelest. On average, they are about as nice as the average person in the whole population, which, let’s face it, is not that nice. And by the same token, the nicest men are only averagely handsome. The ugly guys you like, though—they make up a tiny corner of the triangle, and they are pretty darn nice. They have to be, or they wouldn't be visible to you at all. The negative correlation between looks and personality in your dating pool is absolutely real. But the relation isn't causal. If you try to improve your boyfriend’s complexion by training him to act mean, you've fallen victim to Berkson's fallacy.

至此,这个现象产生的根源已经很清楚了,在你的三角中,最帅的人位于最右边的线上,它几乎囊括了人的所有品性,从最宽厚的到(几乎)最残忍的。平均而言,他们的友好程度跟全体男人的平均友好水平差不多,但是,我们必须正视,这个友好程度并不十分友好。同理可得,最友好的男人的相貌也只达到全体男人的平均水平。而那些你能看上的丑男们,他们可真是友好的不像话啊,虽然他们只占了三角中的一个很小的角落。不过他们必须得是这样的,否则怎么入得了你的法眼。约会对象的相貌和品性之间具有负相关性,这是绝对真实的。但是这种相关性并不具备因果关系。千万别想着通过训练男友行为卑劣,就能使他们的相貌增色几分,否则你就沦为伯克逊谬误的牺牲品了。

The fallacy works, too, as a driver of literary snobbery. Why are popular novels so terrible? It’s not because the masses don’t appreciate quality. It’s because the novels you read are the ones in the Acceptable Triangle, which are either popular or good. So within that group, the good ones are less likely to be popular, for the same reason the handsomer men are bigger jerks. If you force yourself to read unpopular novels chosen essentially at random—I've been on a jury for a literary prize, so I've actually done this—you find that most of them, just like the popular ones, are pretty bad. And I imagine if you dated men chosen completely at random from OkCupid, you’d find that the less attractive men were just as jerky as the chiseled hunks. But that’s an experiment I can’t recommend, not even for the sake of mathematical enlightenment.

此谬误也是文学上的势力现象产生的驱动力之一。为什么流行小说评价如此糟糕?并非是大众不懂得欣赏,而是因为每个人读的小说只在自己能接受的三角范围内,它们要么流行,要么很好。在这个范围内,好的小说更可能不那么流行,就好比那些比较帅气的男人更可能是个大混蛋!如果你强迫自己读一些完全随机选择的非流行小说(我曾经当过一个文学奖的评委,所以我确实这么干过),你会发现它们中的大多数,都非常的糟糕,就跟流行小说的表现一样。而且我能想像,如果你从OkCupid上完全随机的选择约会对象,你会发现那些不怎么具有吸引力的男人和俊朗的帅哥一样混蛋。不过我可不推荐这个实验,即便是打着数学启蒙的旗号。

And now what happened to Julian Barnes is pretty clear. There are two reasons you might have read The Sense of an Ending and rated it on Goodreads. It might be because it’s exactly the kind of novel you’re apt to like. Or it might be because it won the Booker Prize. When a book wins a prize, then its audience expands beyond the core group of fans already predisposed to love it. That’s what every author dreams of, but more frequently read inevitably means less universally liked.

至此,朱利安·巴恩斯的遭遇已经相当明了。你可能已经读过The Sense of an Ending,并且在Goodreads上给它打了分。这其中的原因可能有两个,一个是因为它恰好就是你会喜欢的那类小说,另一个是因为它获得了布克奖。如果一本书获了奖,那么它的读者就不仅仅是那些之前就已经很热爱它的核心粉丝群体了。获奖是每一个作家梦寐以求的事情,但是一本书被读到的越频繁,喜欢它的读者的比例就越低。