(单词翻译:单击)

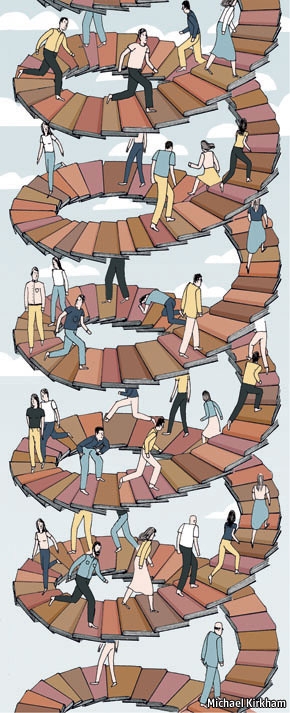

ON THE evening before All Saints' Day in 1517, Martin Luther nailed 95 theses to the door of a church in Wittenberg. In those days a thesis was simply a position one wanted to argue. Luther, an Augustinian friar, asserted that Christians could not buy their way to heaven. Today a doctoral thesis is both an idea and an account of a period of original research. Writing one is the aim of the hundreds of thousands of students who embark on a doctorate of philosophy (PhD) every year.

1517年10月31日,也就是万圣节前夜,马丁·路德在威登堡城堡大教堂门口以学术争论方式张贴出欢迎辩论的《九十五条论点》。在那个时代,论文只是阐述作者观点。这位新教创始人路德在论文中论证了基督教通往天国的道路,其实不是由金钱铺筑而成。而今天,学术论文不仅仅阐述作者观点,同时还代表作者的一段时期内的研究成果。每年都有成千上万的学生们想要拿到博士学位,前赴后继辛苦劳累,就是为了完成这样一篇博士论文。

In most countries a PhD is a basic requirement for a career in academia. It is an introduction to the world of independent research—a kind of intellectual masterpiece, created by an apprentice in close collaboration with a supervisor. The requirements to complete one vary enormously between countries, universities and even subjects. Some students will first have to spend two years working on a master's degree or diploma. Some will receive a stipend; others will pay their own way. Some PhDs involve only research, some require classes and examinations and some require the student to teach undergraduates. A thesis can be dozens of pages in mathematics, or many hundreds in history. As a result, newly minted PhDs can be as young as their early 20s or world-weary forty-somethings.

在大多数国家,博士学位是进入学术界的门槛,进入独立研究某个领域的敲门砖,也是与导师合作的研究成果。各个国家,不同大学,不同专业,要求也有所不同。有些要求学生两年时间才能拿到硕士学位,有的学生会得到一些补助,而有些完全是自费。获得博士学位只需要完成研究论文,而有些还需要参加一些必修课或选修课或是助教工作。一篇学术论文有几十页,甚至是几百页。这些博士有的还是二十出头的小伙儿,有些已经是知天命的四十岁中年人了。

One thing many PhD students have in common is dissatisfaction. Some describe their work as “slave labour”. Seven-day weeks, ten-hour days, low pay and uncertain prospects are widespread. You know you are a graduate student, goes one quip, when your office is better decorated than your home and you have a favourite flavour of instant noodle. “It isn't graduate school itself that is discouraging,” says one student, who confesses to rather enjoying the hunt for free pizza. “What's discouraging is realising the end point has been yanked out of reach.”

这些读博的学生们有一点是相同的:即对现状不满。有的把自己的工作描述为打工仔,每周七天无休息,二十四小时待命,薪酬很少,前途渺茫。这种情况很普遍。如果你已经博士毕业,回顾读博那段经历,可能会说,那个时候,我的办公室比现在的家都要阔气,而且经常吃方便面。一位求学者说,本质问题是研究本身让我感到枯燥。他很坦诚地说,天上不可能掉馅饼。

Whining PhD students are nothing new, but there seem to be genuine problems with the system that produces research doctorates (the practical “professional doctorates” in fields such as law, business and medicine have a more obvious value). There is an oversupply of PhDs. Although a doctorate is designed as training for a job in academia, the number of PhD positions is unrelated to the number of job openings. Meanwhile, business leaders complain about shortages of high-level skills, suggesting PhDs are not teaching the right things. The fiercest critics compare research doctorates to Ponzi or pyramid schemes.

在读博士抱怨满腹早已不是什么新鲜事,现象背后的本质问题在于培养博士体系本身。应用性博士,比如法学博士、商学博士和药学博士,实际上含金量很高。而博士泛滥成灾供过于求,尽管博士学位的设置是为进入学术界而考虑,但是现在存在的问题是,授予博士学位的数量和现有的研究岗位数量差距拉大。博士供过于求,而很多企业领导又说他们找不到所需的高级技术人才。从一方面也表明博士们并没有学到企业所需的知识技能。一些人甚至把研究型博士的培养体系比作旁氏原理。

Rich pickings For most of history even a first degree at a university was the privilege of a rich few, and many academic staff did not hold doctorates. But as higher education expanded after the second world war, so did the expectation that lecturers would hold advanced degrees. American universities geared up first: by 1970 America was producing just under a third of the world's university students and half of its science and technology PhDs (at that time it had only 6% of the global population). Since then America's annual output of PhDs has doubled, to 64,000.

从历史上看有相当一段时间,如果说进入一流大学读书还是少数富人才能得到的特权,甚至很多大学教师都没有博士学位。而二战后,高校不断扩招,于此同时大学讲师也需要有较高学历。到1970年,美国的大学就是如此,数量不到三分之一,却颁发了全球自然科学和工科博士的一半人数。在这段时期美国人口仅占全世界人口的6%,从此之后,美国每年博士数量不断翻倍,每年达到6.4万人。

Other countries are catching up. Between 1998 and 2006 the number of doctorates handed out in all OECD countries grew by 40%, compared with 22% for America. PhD production sped up most dramatically in Mexico, Portugal, Italy and Slovakia. Even Japan, where the number of young people is shrinking, churned out about 46% more PhDs. Part of that growth reflects the expansion of university education outside America. Richard Freeman, a labour economist at Harvard University, says that by 2006 America was enrolling just 12% of the world's students.

其他国家也纷纷赶上。在1998年至2006年,经合组织国家颁发的博士学位数量增长了40%,同时美国增长了22%。在墨西哥、葡萄牙、意大利、斯洛伐克等国家博士产出也增长很快。甚至在年轻人口减少的日本,也以46%的增速培养了大批博士。这些增长也看出美国以外的其他国家的高等教育在迅猛发展。哈佛大学劳动经济学家理查德·费里曼说,到2006年,美国高校招生数量占世界12%。

But universities have discovered that PhD students are cheap, highly motivated and disposable labour. With more PhD students they can do more research, and in some countries more teaching, with less money. A graduate assistant at Yale might earn $20,000 a year for nine months of teaching. The average pay of full professors in America was $109,000 in 2009—higher than the average for judges and magistrates.

同时,许多大学形成了一个共识,在读博士积极性很高,因而是可以任意指使的廉价劳动力。招手博士有助于学校开展研究项目,这些博士生还可用来发展教育,而且成本少。一位耶鲁大学研究生助教九个月的收入为2万美元,2009年全美在职教授平均年薪为10.9万美元,高于法官和地方官员。

Indeed, the production of PhDs has far outstripped demand for university lecturers. In a recent book, Andrew Hacker and Claudia Dreifus, an academic and a journalist, report that America produced more than 100,000 doctoral degrees between 2005 and 2009. In the same period there were just 16,000 new professorships. Using PhD students to do much of the undergraduate teaching cuts the number of full-time jobs. Even in Canada, where the output of PhD graduates has grown relatively modestly, universities conferred 4,800 doctorate degrees in 2007 but hired just 2,616 new full-time professors. Only a few fast-developing countries, such as Brazil and China, now seem short of PhDs.

博士年产量远远高出了大学对讲师的需求,最新出版一本书中,美国在2005年至2009年一共培养了10万名博士,与此同时,大学教师职位需求仅仅为1.6万人,这本书两位作者是一位学者和一名记者。在读博士去做助教更减少了对全职教师的需求。甚至在加拿大,博士毕业生增长较为合理的国家,2007年授予了48000人博士学位,同时增加了26160人做为全职教师,而一些增长较快的国家,比如巴西和中国,似乎对博士需求量大一些。

A short course in supply and demand In research the story is similar. PhD students and contract staff known as “postdocs”, described by one student as “the ugly underbelly of academia”, do much of the research these days. There is a glut of postdocs too. Dr Freeman concluded from pre-2000 data that if American faculty jobs in the life sciences were increasing at 5% a year, just 20% of students would land one. In Canada 80% of postdocs earn $38,600 or less per year before tax—the average salary of a construction worker. The rise of the postdoc has created another obstacle on the way to an academic post. In some areas five years as a postdoc is now a prerequisite for landing a secure full-time job.

研究领域情况类似,在读博士学习期间做了大量的研究工作,学生们称为“软肋”,现在博士后也是供过于求,付瑞曼博士的结论是:数据表明,2000年美国生命科学领域教工需求每年增长5%,这些博士和博士后学生里面,仅仅有五分之一能找到工作。在加拿大,80%的博士后每年收入是3.86万美元甚至更少,而这是建筑工人的平均薪资,博士后数量增加成了博士们通往学术道路的一种阻碍,在有些国家,五年博士后才是获得一份全职工作的敲门砖。

These armies of low-paid PhD researchers and postdocs boost universities', and therefore countries', research capacity. Yet that is not always a good thing. Brilliant, well-trained minds can go to waste when fashions change. The post-Sputnik era drove the rapid growth in PhD physicists that came to an abrupt halt as the Vietnam war drained the science budget. Brian Schwartz, a professor of physics at the City University of New York, says that in the 1970s as many as 5,000 physicists had to find jobs in other areas.

这些如蚂蚁般不断增长的博士和博士后们使得大学的研究事业蒸蒸日上,同时也增加了一个国家科研能力,但并不能单纯看成是一件好事。在某些情况下,受到良好培训教育的高学历者自身才能极大的浪费了。美国在研究定点地球卫星时,物理学博士数量激增,而过后数量急剧下降,越南战争削减了科研计划。一位美国纽约城市大学的物理学教授史沃兹说,20世纪70年代,大约有5000位物理学家不得不该行另谋出路。

In America the rise of PhD teachers' unions reflects the breakdown of an implicit contract between universities and PhD students: crummy pay now for a good academic job later. Student teachers in public universities such as the University of Wisconsin-Madison formed unions as early as the 1960s, but the pace of unionisation has increased recently. Unions are now spreading to private universities; though Yale and Cornell, where university administrators and some faculty argue that PhD students who teach are not workers but apprentices, have resisted union drives. In 2002 New York University was the first private university to recognise a PhD teachers' union, but stopped negotiating with it three years later.

在美国,博士教师的工会也随之兴起,解决博士生教师与学校之间的一些矛盾。大学给他们花了一张大饼,即用今天的廉价劳动来换取未来的一份稳定学术工作。像威斯康星麦迪逊这样的大学,工会建立可以追溯到1960年。而真正的工会兴起还是近几年的事。如今,工会也深入到私立大学。在耶鲁和康奈尔大学,行政管理人员和教师说博士不能算是正式员工,只能是学徒而已。这些话受到了来自工会的压力。2002年,纽约城市大学作为第一个承认博士教师工会存在的私立大学,但三年之后,这所学校停止了工会活动。

In some countries, such as Britain and America, poor pay and job prospects are reflected in the number of foreign-born PhD students. Dr Freeman estimates that in 1966 only 23% of science and engineering PhDs in America were awarded to students born outside the country. By 2006 that proportion had increased to 48%. Foreign students tend to tolerate poorer working conditions, and the supply of cheap, brilliant, foreign labour also keeps wages down.

在美国和英国,很多博士都忍受着低收入低报酬的职业并且看不到前景。在1966年,仅仅23%的自然科学和工科博士文凭颁发给了外国学生。到2006年,这个比例增加到48&,与本土学生相比,国外学生更能忍受艰苦研究工作环境,与此同时,他们的薪酬大大降低。

Proponents of the PhD argue that it is worthwhile even if it does not lead to permanent academic employment. Not every student embarks on a PhD wanting a university career and many move successfully into private-sector jobs in, for instance, industrial research. That is true; but drop-out rates suggest that many students become dispirited. In America only 57% of doctoral students will have a PhD ten years after their first date of enrolment. In the humanities, where most students pay for their own PhDs, the figure is 49%. Worse still, whereas in other subject areas students tend to jump ship in the early years, in the humanities they cling like limpets before eventually falling off. And these students started out as the academic cream of the nation. Research at one American university found that those who finish are no cleverer than those who do not. Poor supervision, bad job prospects or lack of money cause them to run out of steam.

支持读博士的人也许会说,即使不能得到一份稳定的研究工作,读博也是值得的。并非每一位读博士的人都想进入大学,也有很多在私营企业,或是企业研发等,都取得了不错的成绩。这的确是事实,但是凡事都有两面,我们看到的事实,博士生退学者增多,很多在读博士很郁闷。在美国,仅仅57%的博士在十年以后继续攻读博士,也就是说其他的都退学了。在人文社会学科领域,自费读博士的学生退学比例是49%。更糟糕的是,其他在读博士,在博士一年级就在不同专业跳来跳去,很多人文学科在读博士坚守着自己的领域,最终很多人不得不放弃了。而辍学者往往成为了国家的学术精英。美国大学一个研究报告表明,按时完成博士学习的人,并不比辍学者睿智多少。缺少职业指导,前途渺茫,经济拮据成了他们最终放弃的原因。

Even graduates who find work outside universities may not fare all that well. PhD courses are so specialised that university careers offices struggle to assist graduates looking for jobs, and supervisors tend to have little interest in students who are leaving academia. One OECD study shows that five years after receiving their degrees, more than 60% of PhDs in Slovakia and more than 45% in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany and Spain were still on temporary contracts. Many were postdocs. About one-third of Austria's PhD graduates take jobs unrelated to their degrees. In Germany 13% of all PhD graduates end up in lowly occupations. In the Netherlands the proportion is 21%.

就算完成了学业,也并非前途光芒。由于博士专业太细,就业工作人员费尽心思帮助博士们求职,而企业老总们对这些想要离开学术的博士生们兴趣不大。经合组织一项研究表明,博士们在取得博士学位后五年,很多还在做临时工作,这一比例在斯洛伐克超过了60%,比利时、捷克、德国和西班牙超过了45%。而大约三分之一的澳大利亚博士们从事与博士专业毫无关系的工作。在德国,13%的博士毕业生从事其他工作,荷兰的比例是21%。

A very slim premium

微薄的回报

PhD graduates do at least earn more than those with a bachelor's degree. A study in the Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management by Bernard Casey shows that British men with a bachelor's degree earn 14% more than those who could have gone to university but chose not to. The earnings premium for a PhD is 26%. But the premium for a master's degree, which can be accomplished in as little as one year, is almost as high, at 23%. In some subjects the premium for a PhD vanishes entirely. PhDs in maths and computing, social sciences and languages earn no more than those with master's degrees. The premium for a PhD is actually smaller than for a master's degree in engineering and technology, architecture and education. Only in medicine, other sciences, and business and financial studies is it high enough to be worthwhile. Over all subjects, a PhD commands only a 3% premium over a master's degree.

博士毕业生的确比本科生薪酬高,《高等教育政策管理》杂志刊登了卡塞的一项研究,在英国,大学毕业生比未上大学者收入高14%。身为博士,回报差只有26%。硕士学位回报同样比博士高,有的硕士一年就可拿到。有些领域博士学位没有任何优势。在数学、计算机、社会科学和语言等领域,博士收入与硕士差不多。在工程、工业技术、建筑和教育领域,博士和硕士收入也差不多。在制药、商学、金融等领域,博士回报与付出差不多。总体说来,博士学位仅仅比硕士学位收入高3%。

Dr Schwartz, the New York physicist, says the skills learned in the course of a PhD can be readily acquired through much shorter courses. Thirty years ago, he says, Wall Street firms realised that some physicists could work out differential equations and recruited them to become “quants”, analysts and traders. Today several short courses offer the advanced maths useful for finance. “A PhD physicist with one course on differential equations is not competitive,” says Dr Schwartz.

纽约一位政治家史沃兹博士说,博士课程中有很多可以用更短课程取代,他说,华尔街发现很多物理学家能够解出微分方程,于是聘请他们做定量分析。但是如今教授却用一些很简单的高等数学课程,因此,一个会解微分方程的博士生不再具有竞争力。

Many students say they are pursuing their subject out of love, and that education is an end in itself. Some give little thought to where the qualification might lead. In one study of British PhD graduates, about a third admitted that they were doing their doctorate partly to go on being a student, or put off job hunting. Nearly half of engineering students admitted to this. Scientists can easily get stipends, and therefore drift into doing a PhD. But there are penalties, as well as benefits, to staying at university. Workers with “surplus schooling”—more education than a job requires—are likely to be less satisfied, less productive and more likely to say they are going to leave their jobs.

很多学生做研究是出于热爱,现在教育却成了终结了他们的热爱。很少人知道路在何方,英国一项对博士毕业生研究数据表明,三分之一人读博只是为了继续做学生,或是延迟就业。大概一半学生说,科学家可以有很高的年薪,因此就随波逐流读博。但是呆在校园,喜忧参半。高学历者更容易不满足更容易跳槽。

The interests of universities and tenured academics are misaligned with those of PhD studentsAcademics tend to regard asking whether a PhD is worthwhile as analogous to wondering whether there is too much art or culture in the world. They believe that knowledge spills from universities into society, making it more productive and healthier. That may well be true; but doing a PhD may still be a bad choice for an individual.

一些人开始怀疑读博是否值得,如同怀疑这个世界太多的艺术和文化。他们认为,知识会从大学渗透到社会各个领域,社会物质文明高度发展,会朝着更加健康的方向。在宏观上是这样,微观方面,读博的确是一个很糟的选择。

The interests of academics and universities on the one hand and PhD students on the other are not well aligned. The more bright students stay at universities, the better it is for academics. Postgraduate students bring in grants and beef up their supervisors' publication records. Academics pick bright undergraduate students and groom them as potential graduate students. It isn't in their interests to turn the smart kids away, at least at the beginning. One female student spoke of being told of glowing opportunities at the outset, but after seven years of hard slog she was fobbed off with a joke about finding a rich husband.

学术研究者、大学、博士生利益各不同。呆在大学的学生更聪明只是对学术有利。硕士研究生可以带来带来更多的财政经费,为导师的学术论文增加数量。这些孩子毕业走出校门,这些对他们来说毫无好处。一位女学生曾经被导师认为前途无量,但七年学术后,最后导师送她一句话,早点嫁人吧。然后导师把她请出了校门。

Monica Harris, a professor of psychology at the University of Kentucky, is a rare exception. She believes that too many PhDs are being produced, and has stopped admitting them. But such unilateral academic birth control is rare. One Ivy-League president, asked recently about PhD oversupply, said that if the top universities cut back others will step in to offer them instead.

肯塔基州大学心理学教授莫里1卡哈里斯说,这样的教授是少数。她认为单方面想要控制博士数量行为很少见到。一位常青藤学校校长被问到博士数量过多时,他回答,即便我们这些学校减少招生博士生,其他学校也会把我们减少的部分给增加上去的。

Noble pursuits

高贵的追求

Many of the drawbacks of doing a PhD are well known. Your correspondent was aware of them over a decade ago while she slogged through a largely pointless PhD in theoretical ecology. As Europeans try to harmonise higher education, some institutions are pushing the more structured learning that comes with an American PhD.

读博士的种种弊端已经众所周知,本文的作者十年前就劝说一位理论生态学方向博士不要继续,当时欧洲也正在促使高等教育体系更完善,一些机构也大力推动。

The organisations that pay for research have realised that many PhDs find it tough to transfer their skills into the job market. Writing lab reports, giving academic presentations and conducting six-month literature reviews can be surprisingly unhelpful in a world where technical knowledge has to be assimilated quickly and presented simply to a wide audience. Some universities are now offering their PhD students training in soft skills such as communication and teamwork that may be useful in the labour market. In Britain a four-year NewRoutePhD claims to develop just such skills in graduates.

资助基金组织已经意识到,博士在劳动力市场中,技能难以发挥。他们会写实验研究报告,会做学术报告,做文献查阅等,但如今这个知识技术快速传播的时代,显得毫无用处。一些大学为博士生开设了其他课程,比如沟通能力、团队合作能力等。这些在求职时或许派上用。在英国有一个四年的博士,他们要为博士开设以上课程。

Measurements and incentives might be changed, too. Some university departments and academics regard numbers of PhD graduates as an indicator of success and compete to produce more. For the students, a measure of how quickly those students get a permanent job, and what they earn, would be more useful. Where penalties are levied on academics who allow PhDs to overrun, the number of students who complete rises abruptly, suggesting that students were previously allowed to fester.

一些大学和科研院所把培养博士数量作为一项指标,并准备培养更多。对学生来说,找到一份实际的固定工作,收入会有多少才更重要。而博士数量已经太多了,博士生不得不面对整体水平越来越下降的窘境。

Many of those who embark on a PhD are the smartest in their class and will have been the best at everything they have done. They will have amassed awards and prizes. As this year's new crop of graduate students bounce into their research, few will be willing to accept that the system they are entering could be designed for the benefit of others, that even hard work and brilliance may well not be enough to succeed, and that they would be better off doing something else. They might use their research skills to look harder at the lot of the disposable academic. Someone should write a thesis about that.

很多读博的人都是班上聪明的学生,他们可以把想做的事做到最好。在人生旅途上得到鲜花和奖赞。每年博士新生都不愿意去相信,他们正在为整个文凭体系效力,我们不要完全否认而得益者不是他们。仅仅有追梁刺骨的刻苦精神与自以为聪明过人不会取得人生的成功。如果把这些精力和时间用到别处或许会做得更好。