(单词翻译:单击)

FOR as long as humans have romanced each other, others have wanted to meddle. Whether those others were parents, priests, friends or bureaucrats, their motive was largely the same: they thought they knew what it took to pair people off better than those people knew themselves.

只要一有人要找对象,周围人就喜欢掺和。这些人,不管是父母、牧师、朋友还是同事,他们的说辞都一个模样:你当局者迷啊,我旁观者清,我比你更知道你该找个什么样的,我来给你参谋参谋。

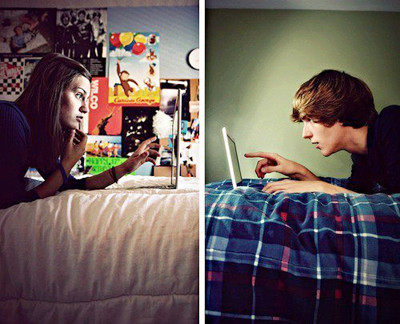

Today, though, there is a new matchmaker in the village: the internet. It differs from the old ones in two ways. First, its motive is purely profit. Second, single wannabe lovers are queuing up to use it, rather than resenting its nagging. For internet dating sites promise two things that neither traditional matchmakers nor chance encounters at bars, bus-stops and bar mitzvahs offer. One is a vastly greater choice of potential partners. The other is a scientifically proven way of matching suitable people together, enhancing the chance of "happily ever after".

如今,网络红娘新加入到这些人当中来。不同于传统媒人的是,这位新式红娘动机单纯到只为挣钱;并且单身人士竞相注册使用,他们一点儿也不像原来那样因讨厌别人的絮叨而感到烦恼。这是为什么呢?原来,婚恋网站许诺了两件事,这两件事旧式红娘办不到,街头邂逅也办不到。其一,网站为单身们提供了大量的候选人;其二,网站总是宣称他们可提供科学方法来帮助单身们找到合适人选,从而能增加伴侣们从此过上幸福生活的机率。

The greater choice is unarguable. But does it lead to better outcomes? And do the "scientifically tested algorithms" actually work, and deliver the goods in ways that traditional courtship (or, at least, flirtation) cannot manage? These are the questions asked by a team of psychologists led by Eli Finkel of Northwestern University, in Illinois, in a paper released—probably not coincidentally—a few days before St Valentine's day. This paper, published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, reviews studies carried out by many groups of psychologists since the earliest internet dating site, Match.com, opened for business in 1995. In it, Dr Finkel and his colleagues cast a sceptical eye over the whole multi-billion-dollar online dating industry, and they are deeply unconvinced.

更多选择这一点毫无疑问,可这确实能带来更好的结果吗?而所谓的科学验证过的算法真的有用吗?这些算法真的能提供传统的追求方式(至少是,调情方式)所办不到的事吗? 美国伊利诺斯州西北大学伊莱·芬克博士领导的一个心理学专家小组关心的正是这些问题,他们恰是在情人节前(也许真的不是巧合)发表了这么一篇论文。这篇论文,发表在《公众心理科学杂志》上,回顾了自最早的婚恋网站Match.com自1995年上线以来各路心理学家为此所做的各种研究成果。在这篇论文中,芬克博士和他的同事们对价值千亿美元的网络婚恋产业投去质疑的目光,而研究结论也确实令他们对本段开头所提的那些问题答案更为怀疑了。

Blueprint for a perfect partner?

完美伴侣蓝图?

The researchers' first observation is not so much what the studies they examined have shown, but what they have been unable to show, namely how any of the much-vaunted partner-matching algorithms actually work.

研究人员最先着手的问题是:被过分夸大的伴侣匹配算法在实战中是如何发挥作用的?这一点并非为之前的研究所验证过,而恰是它们未能展示的部分。

Commercially, that is fair enough. Many firms preserve their intellectual property as trade secrets, rather than making it public by patenting it, and there is no reason why internet dating sites should not be among them. But this makes claims of efficacy impossible to test objectively. There is thus no independent scientific evidence that any internet dating site's algorithm for matching people together actually does enhance the chance of their hitting it off when they meet. What papers have been published on the matter have been written by company insiders who do not reveal how the crucial computer programs do their stuff.

从商业角度看,这并无不妥。很多公司都会将其智力成果作为商业机密而加以保护,根本不会去申请专利而使之公开,那么婚恋网站就没理由不在其中啊。可这当然就会使得其所声称的有效性得不到客观验证。于是,根本就不存在独立客观的科学证据可以证明婚恋网站所发布的配对算法能够增加人们相遇后互相觉得投缘的机率。有关这方面的发表论文均出自网站内部工作人员,他们根本就不会透露这个关键的电脑程序是如何进行计算的。

It is, though, possible to test the value of a claim often made for these algorithms: that they match people with compatible personality traits. No doubt they do, given the number of questions on such matters on the average application form. What is assumed, but not tested, however, is that this is a good thing—that those with compatible personalities make more successful couples than those without. To examine this proposition, Dr Finkel draws on a study published in 2010 by Portia Dyrenforth of Hobart and William Smith Colleges, in Geneva, New York.

然而,去验证这些算法所归纳的结论又似乎是可能的:网站总是挑出那些具备包容性格的人进行配对。假设他们在申请表中列上一些有关这类性格的问题,电脑肯定能做到这件事。可是,这种说法与其说是种验证不如说是种猜测——即假设那些具备包容性格的人比那些不太包容的人更容易找到对象。为了检验这个命题,芬克博士引用了刊登于2010年的一项研究成果,这项研究由位于美国纽约州日内瓦城的霍巴特威廉史密斯学院的波西亚·德莱佛斯(Portia Dyrenforth)所做。

Dr Dyrenforth asked more than 20,000 people about their relationships, and also assessed their personalities. Members of couples with similar personalities were indeed happier than those whose partners were dissimilar. But the difference was not exactly huge. It was 0.5%. As Dr Finkel puts it, "I wouldn't have a problem with companies claiming that their matching algorithm could increase the chances of developing a lasting relationship by a tiny amount; I get concerned, though, when companies claim they can find your soul mate for you."

德莱佛斯博士对超过2万人进行了调查,问题涉及人们的伴侣关系以及性格评估。伴侣双方性格相近的确实比性格差异较大的更觉幸福一些。但从数量上看,这个差别真的不大,只有0.5%的差距。芬克博士说:假如网站说其配对算式能够令人们配对成功的概率有小幅上升,我对此毫无意见。可是他们说网站能帮你找到真爱,我就觉得有问题了。

Surely, however, the chances of finding that magic other are increased by the second thing internet dating brings: oodles of choice? But here, too, things are not as simple as they might seem.

或许网络能带来的第二点益处——大量选择——能增加人们找到另一伴的机会?不过同样的,事实也并不像人们想得那么简单。

Some dating-site algorithms do not take the high-handed "we know best" approach but, rather, let the punter decide what he or she is looking for and then offer as many matches to those criteria as are on the website's books.

有些网站并不采用武断的我们最懂你策略,相反,他们让用户自已去决定想要找的类型,网站就是尽可能多的按照用户标准提供候选人。

The crucial assumption here, of course, is that what people think they want is what they actually need. That, it is true, is an assumption behind all consumer decisions. But changing your mind about a book or a washing machine chosen over the internet is not as emotionally fraught as changing your mind about a potential sexual partner. And here, too, the data suggest people are not good at knowing what they want. One of Dr Finkel's own studies, for example, showed that when they are engaged in internet dating's cousin, speed dating, people's stated preferences at the beginning of the process do not well match the characters of the individuals they actually like.

当然,这里有一个关键假设是人们总是认为他们想要的就是他们需要的。这个假设实际上适用于所有的消费者决定。对于上网选购一本书或一台洗衣机你可以这么做,可是上网去选择一位潜在的性伴你这么做就太过感性了吧。而且,有数据显示人们其实并不如自己想像中的那样了解自己的需求。举个芬克博士自己的研究成果来说吧,此案例显示:当人们沉溺于网络相亲,快速约会时,人们在这些活动初始时的表现出来的性格特征与喜好与他本身的个性特征是非常不一样的。

Indeed, even the very volume of alternatives may be a problem. Studies on consumer choice, from boxes of chocolates to restaurant wine lists, have shown that less is more. Half a dozen bonbons, or a dozen bottles, are easier to pick between than 30 or 40. And an internet dating site may come up with not just a few dozen, but thousands of allegedly suitable matches.

没错,甚至这巨大的可供选择量都可能是个问题。消费者心理学告诉我们,少即是多,从在超市选择一盒巧克力到在饭馆挑瓶葡萄酒,这都是已被证实了的一个道理。从6盒棒棒糖中挑出一盒,或从一打酒中选出一瓶总是比从30、40个中选更容易些。可是婚恋网站给你提供了多少选择?可不是几十个,那是好几千所谓适合你的人选啊。

The supermarket of love

爱情超市

Not surprisingly, the difficulty of choosing from abundance seems to apply to choice of people, too. Dr Finkel could find no study which addressed the question directly, in the context of internet dating. But speed-dating once again provided an answer. Here, he found studies which showed that when faced with abundant choice, people pay less attention to characteristics that require thinking and conversation to evaluate (occupational status and level of education, for example) and more to matters physical. Choice, in other words, dulls the critical faculties.

将 选择困难放到人身上同样适用,这没什么好奇怪的。不过将这一点放在婚恋网站中来考察,芬克博士确实没有找到相关研究。不过,有关快速约会的研究又一次告诉了我们答案。芬克发现这些研究表明,当人们面对大量选择时,对于那些需要通过交谈和思考才能了解的特质,人们倾注的注意力会减少(比如职业状况、教育背景等),反之对那些外在特征则更为关注。换句话说,大量选择屏蔽了人们对重要关键特质的判断力。

The upshot of Dr Finkel's review is thus that love is as hard to find on the internet as elsewhere. That is not a reason not to use it. But you may be just as likely to luck out in the local café, or by acting on the impulse to stop and talk to that stranger on the street whose glance you caught, as you are by clicking away with a mouse and hoping that, one day, Cupid's arrow will strike.

芬克博士研究的结论要点可以总结为:在网上寻找真爱并不比其他地方容易。但这并非是一条拒绝用网络的理由。你在街角的咖啡馆可能幸运地邂逅心上人;你也可以在踯躅于街头时,忽然被陌生人一个眼神所打动便冲动地停下来和人家搭讪;所以当然,你也可以动一动鼠标,并且祈祷忽然有一天,自己幸运地被丘比特神箭击中。