(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

Aureliano did not understand until then how much he loved his friends, how much he missed them, and how much he would have given to be with them at that moment. He put the child in the basket that his mother had prepared for him, covered the face of the corpse with a blanket, and wandered aimlessly through the town, searching for an entrance that went back to the past. He knocked at the door of the pharmacy, where he had not visited lately, and he found a carpenter shop. The old woman who opened the door with a lamp in her hand took pity on his delirium and insisted that, no, there had never been a pharmacy there, nor had she ever known a woman with a thin neck and sleepy eyes named Mercedes. He wept, leaning his brow against the door of the wise Catalonian’s former bookstore, conscious that he was paying with his tardy sobs for a death that he had refused to weep for on time so as not to break the spell of love. He smashed his fists against the cement wall of The Golden Child, calling for Pilar Ternera, indifferent to the luminous orange disks that were crossing the sky and that so many times on holiday nights he had contemplated with childish fascination from the courtyard of the curlews. In the last open salon of the tumbledown red-light district an accordion group was playing the songs of Rafael Escalona, the bishop’s nephew, heir to the secrets of Francisco the Man. The bartender, who had a withered and somewhat crumpled arm because he had raised it against his mother, invited Aureliano to have a bottle of cane liquor, and Aureliano then bought him one. The bartender spoke to him about the misfortune of his arm. Aureliano spoke to him about the misfortune of his heart, withered and somewhat crumpled for having been raised against his sister. They ended up weeping together and Aureliano felt for a moment that the pain was over. But when he was alone again in the last dawn of Macondo, he opened up his arms in the middle of the square, ready to wake up the whole world, and he shouted with all his might:

“Friends are a bunch of bastards!?

Nigromanta rescued him from a pool of vomit and tears. She took him to her room, cleaned him up, made him drink a cup of broth. Thinking that it would console him, she took a piece of charcoal and erased the innumerable loves that he still owed her for, and she voluntarily brought up her own most solitary sadnesses so as not to leave him alone in his weeping. When he awoke, after a dull and brief sleep, Aureliano recovered the awareness of his headache. He opened his eyes and remembered the child.

直到此刻,奥雷连诺·布恩蒂亚才感到自己多么热爱自已的朋友们,多么需要他们,为了在这一瞬间能和他们相处一起,他是愿意付出任何代价的。他把婴儿安放在阿玛兰塔·乌苏娜生前准备的摇篮里,又用被子蒙住死者的脸,然后就独自在空旷的小镇上踯躅,寻找通往昔日的小径,他先是敲那家药房的门。他已经好久没来这儿了,发现药房所在地变成了木器作坊,给他开门的是一个老太婆,手里提着一盏灯。她深表同情地原谅他敲错了门,但执拗地肯定说,这儿不是药房,从来不曾有过药居,她有生以来从没见过一个名叫梅尔塞德斯的、脖子纤细、睡眠惺怪的女人。当他把额头靠在博学的加泰隆尼亚人昔日的书店门上时,禁不住啜泣起来,他懊悔自己当初不愿摆脱爱情的迷惑,没能及时为博学的加泰隆尼亚人的逝世哀悼,如今只能献上一串串悔恨的眼泪。他又挥动拳头猛击“金童”的水泥围墙,不住地呼唤着皮拉·苔列娜。此时,他根本没有注意到天上掠过一长列闪闪发光的橙黄色小圆盘,而他过去曾在院子里怀着儿童的天真,不知多少次观看过这种小圆盘。在荒芜的妓院区里,在最后一个完好无损的沙龙里,几个拉手风琴的正在演奏弗兰西斯科人的秘密继承者———个主教的侄女——拉法埃尔·埃斯卡洛娜的歌曲。沙龙主人的一只手枯萎了,仿佛被烧过了,原来有一次他竟敢举手揍他的母亲。他邀奥雷连诺·布恩蒂亚共饮一瓶酒,奥雷连诺。 布恩蒂亚也请他喝了一瓶。沙龙主人向他讲了讲他那只手遭到的不幸,奥雷连诺·布恩蒂亚也向沙龙主人谈了谈他心灵的创伤,他的心也枯萎了,仿佛也被烧过了,因为他竟敢爱上了自己的姑姑。临了,他们两人都扑籁簌地掉下了眼泪,奥雷连诺。 布恩蒂亚感到自己的痛苦霎那间消失了。但他独自一人沐浴在马孔多历史上最后的晨曦中,站在广场中央的时候,禁不住张开手臂,象要唤醒整个世界似的,发自内心地高喊道:

“所有的朋友原来全是些狗崽子!”

最后,尼格罗曼塔把他从一汪泪水和一堆呕出的东西中拖了出来。她把他带到自己的房间里,把他身上擦干净,又让他喝了一碗热汤·想到自己的关心能够安慰他,尼格罗曼塔便一笔勾销了他至今还没偿还她的多日情场之账,故意提起自己最忧愁、最痛苦的心事,免得奥雷连诺。 布恩蒂亚独自一人哭泣。翌日拂晓,在短暂地沉睡了一觉之后,奥雷连诺。 布恩蒂亚醒了过来,他首先感到的是可怕的头痛,然后睁开眼睛,想起了自已的孩子。

背景阅读

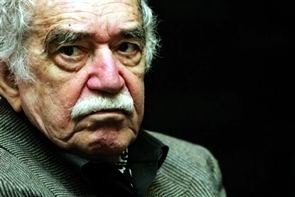

作者简介:

加西亚·马尔克斯(1927一)哥伦比亚作家,记者。生于马格达莱纳省阿拉卡塔卡镇。父亲是个电报报务员兼顺势疗法医生。他自小在外祖父家中长大。外祖父当过上校军官,性格善良、倔强,思想比较激进;外祖母博古通今,善讲神话传说及鬼怪故事,这对作家日后的文学创作有着重要的影响。

加西亚·马尔克斯作品的主要特色是幻想与现实的巧妙结合,以此来反映社会现实生活,审视人生和世界。重要作品有长篇小说《百年孤独》(1967)《家长的没落》(1975)、《霍乱时期的爱情》(1985)等。

本书简介:

《百年孤独》内容复杂,人物众多,情节离奇,手法新颖。马尔克斯在书中溶汇了南美洲特有的五彩缤纷的文化。他通过描写小镇马孔多的产生、兴盛到衰落、消亡,表现了拉丁美洲令人惊异的疯狂历史。小说以“汇集了不可思议的奇迹和最纯粹的现实生活”荣获1982年诺贝尔文学奖。

创作历程:

从1830年至十九世纪末的70年间,哥伦比亚爆发过几十次内战,使数十万人丧生。本书以很大的篇幅描述了这方面的史实,并且通过书中主人公带有传奇色彩的生涯集中表现出来。政客们的虚伪,统治者们的残忍,民众的盲从和愚昧等等都写得淋漓尽致。作家以生动的笔触,刻画了性格鲜明的众多人物,描绘了这个家族的孤独精神。在这个家族中,夫妻之间、父子之间、母女之间、兄弟姐妹之间,没有感情沟通,缺乏信任和了解。尽管很多人为打破孤独进行过种种艰苦的探索,但由于无法找到一种有效的办法把分散的力量统一起来,最后均以失败告终。这种孤独不仅弥漫在布恩迪亚家族和马孔多镇,而且渗入了狭隘思想,成为阻碍民族向上、国家进步的一大包袱。

作家写出这一点,是希望拉丁美洲民众团结起来,共同努力摆脱孤独。所以,《百年孤独》中浸淫着的孤独感,其主要内涵应该是对整个苦难的拉丁美洲被排斥现代文明世界的进程之外的愤懑[mèn]和抗议,是作家在对拉丁美洲近百年的历史、以及这块大陆上人民独特的生命力、生存状态、想象力进行独特的研究之后形成的倔强的自信。这个古老的家族也曾经在新文明的冲击下,努力的走出去寻找新的世界,尽管有过畏惧和退缩,可是他们还是抛弃了传统的外衣,希望溶入这个世界。可是外来文明以一种侵略的态度来吞噬这个家族,于是他们就在这样一个开放的文明世界中持续着“百年孤独”。作者表达着一种精神状态的孤独来批判外来者对拉美大陆的一种精神层面的侵略,以及西方文明对拉美的歧视与排斥。“羊皮纸手稿所记载的一切将永远不会重现,遭受百年孤独的家族,注定不会在大地上第二次出现了。” 作者用一个毁灭的结尾来表达了自己深深的愤懑。