(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

IN THE BEWILDERMENT of her last years, úrsula had had very little free time to attend to the papal education of José Arcadio, and the time came for him to get ready to leave for the seminary right away. Meme, his sister, dividing her time between Fernanda's rigidity and Amaranta's bitterness, at almost the same moment reached the age set for her to be sent to the nuns' school, where they would make a virtuoso on the clavichord of her. úrsula felt tormented by grave doubts concerning the effectiveness of the methods with which she had molded the spirit of the languid apprentice Supreme Pontiff, but she did not put the blame on her staggering old age or the dark clouds that barely permitted her to make out the shape of things, but on something that she herself could not really define and that she conceived confusedly as a progressive breakdown of time. "The years nowadays don't pass the way the old ones used to," she would say, feeling that everyday reality was slipping through her hands. In the past, she thought, children took a long time to grow up. All one had to do was remember all the time needed for José Arcadio, the elder, to go away with the gypsies and all that happened before he came back painted like a snake and talking like an astronomer, and the things that happened in the house before Amaranta and Arca-dio forgot the language of the Indians and learned Spanish. One had to see only the days of sun and dew that poor José Arcadio Buendía went through under the chestnut tree and all the time weeded to mourn his death before they brought in a dying Colonel Aureli-ano Buendía, who after so much war and so much suffering from it was still not fifty years of age. In other times, after spending the whole day making candy animals, she had more than enough time for the children, to see from the whites of their eyes that they needed a dose of castor oil. Now, however, when she had nothing to do and would go about with José Arcadio riding on her hip from dawn to dusk, this bad kind of time compelled her toleave things half done. The truth was that úrsula resisted growing old even when she had already lost count of her age and she was a bother on all sides as she tried to meddle in everything and as she annoyed strangers with her questions as to whether they had left a plaster Saint Joseph to be kept until the rains were over during the days of the war. No one knew exactly when she had begun to lose her sight. Even in her later years, when she could no longer get out of bed, it seemed that she was simply defeated by decrepitude, but no one discovered that she was blind. She had noticed it before the birth of José Arcadio. At first she thought it was a matter of a passing debility and she secretly took marrow syrup and put honey on her eyes, but quite soon she began to realize that she was irrevocably sinking into the darkness, to a point where she never had a clear notion of the invention of the electric light, for when they put in the first bulbs she was only able to perceive the glow. She did not tell anyone about it because it would have been a public recognition of her uselessness. She concentrated on a silent schooling in the distances of things and peoples voices, so that she would still be able to see with her memory what the shadows of her cataracts no longer allowed her to. Later on she was to discover the unforeseen help of odors, which were defined in the shadows with a strength that was much more convincing than that of bulk and color, and which saved her finally from the shame of admitting defeat. In the darkness of the room she was able to thread a needle and sew a buttonhole and she knew when the milk was about to boil. She knew with so much certainty the location of everything that she herself forgot that she was blind at times. On one occasion Fernanda had the whole house upset because she had lost her wedding ring, and úrsula found it on a shelf in the children's bedroom. Quite simply, while the others were going carelessly all about, she watched them with her four senses so that they never took her by surprise, and after some time she discovered that every member of the family, without realizing it, repeated the same path every day, the same actions, and almost repeated the same words at the same hour. Only when they deviated from meticulous routine did they run the risk of losing something. So when she heard Fernanda all upset be cause she had lost her ring, úrsula remembered that the only thing different that she had done that day was to put the mattresses out in the sun because Meme had found a bedbug the might before. Since the children had been present at the fumigation, úrsula figured that Fernanda had put the ring in the only place where they could not reach it: the shelf. Fernanda, on the other hand, looked for it in vain along the paths of her everyday itinerary without knowing that the search for lost things is hindered by routine habits and that is why it is so difficult to find them.

The rearing of José Arcadio helped úrsula in the exhausting task of keeping herself up to date on the smallest changes in the house. When she realized that Amaranta was dressing the saints in the bedroom she pretended to show the boy the differences in the colors.

"Let's see," she would tell him. "Tell me what color the Archangel Raphael is wearing."

在最后几年的混乱中,乌苏娜还来不及抽出足够的空闲时间来好好地教育霍·阿卡蒂奥,使他能够当上一个教皇,而送他去神学院的时间就已到了,所以不得不慌仓仓地准备。霍·阿卡蒂奥的妹妹梅梅是由严峻的菲兰达和沮丧的阿玛兰塔共同照顾的,几乎同时达到了可以进入修道院学校的年龄;她们想在那儿把她培养成为一个出色的钢琴手。乌苏娜疑虑重重地觉得,把萎靡不振的人培养成为教皇,她的方法是不够有效的,但她并不归咎于自己的老迈,也不怪遮住视线的一片云曦,——透过这片云曦,她只能吃力地辨别周围各种东西的轮廓,——而一切都要怪她自己还不确切了解的某种现象,她只模糊地觉得那种现象就是世态的恶化。“现在的年月跟从前完全不同啦,”她感到自己把握不住每天的现实,抱怨地说。从前,她想,孩子长得挺慢嘛。只消回忆一下就够了:在她的大儿子霍·阿卡蒂奥跟吉卜赛人逃走之前,过了乡长的时间啊,而在他全身画得象一条蛇,说着星相家怪里怪气的话,回到家里的时候,发生了多少事情啊,而且在阿玛兰塔和阿卡蒂奥忘掉印第安语、学会西班牙语之前,家中什么事没有发生呀!再想想吧,可怜的霍·阿·布恩蒂亚在菜树下面呆了多少个日日夜夜,家里的人为他哀悼了多久,然后奄奄一总的奥雷连诺上校才给抬回家来,当时他还不满五十岁,并且经历了那么长久的战争和那么多的苦难。从前,她成天忙于自己的糖果,还能照顾子孙,凭他们的眼白就知道该把蓖麻油滴在他们眼里。现在她完全空闲下来,从早到晚仅仅照顾霍·阿卡蒂奥一个人的时候,由于时世不佳,她几乎无法把任何一件事儿干完了。实际上,乌苏娜即使年事已高,但是仍不服老:她什么事都要操心,任何事都要管,而且总是询问外来的人,他们曾否在战争时期把圣约瑟夫的石膏像留在这儿,等雨季过了就来取走。谁也不能确凿地说,乌苏娜是什么时候丧失视觉的。即使在她生前的最后几年,她已经不能起床时,大家还以为她只是老朽了,谁也没有发现她完全瞎了。乌苏娜自己是在霍·阿卡蒂奥出生之前不久感到自己快要失明的。起初,她以为这是暂时的虚弱,悄悄地喝点儿骨髓汤,在眼里滴点儿蜂蜜;可她很快就相信自己正在绝望地陷入黑暗。乌苏娜对电灯始终没有明确的概念,因为马孔多开始安装电灯时,她只能把它当成一种朦胧的亮光。她没有向任何人说她快要瞎了,因为这么一说就是公开承认自己无用了。乌苏娜背着大家,开始坚持不懈地研究各种东西之间的距离和人的声音,想在白内障的阴影完全挡住她的视线时,仍能凭记忆知道各种东西的位置。随后,她又意外地得到了气味的帮助;在黑暗中,气味比轮廓和颜色更容易辨别,终于使别人没有发现她是瞎子。尽管周围一片漆黑,乌苏娜还能穿针引线,缭扣门,及时发现牛奶就要煮沸。她把每件东西的位置记得那么清楚,有时甚至忘了自己眼瞎了。有一次,菲兰达向整座房子大叫大嚷,说她的订婚戒指不见了,乌苏娜却在小孩儿卧室里的隔板上找到了它。道理是很简单的:当其他的人在房子里漫不经心地来来去去时,乌苏娜就凭自己剩下的四种感官注意别人的活动,使得谁也不会突然撞着她;很快她就发现,而家里的每个人却没觉察到。他们每天走的都是同样的路,重复同样的动作,同样的时匆几乎说同样的话。只有偏离常规的时候,他们才会失掉什么东西。所以,听到菲兰达哭哭叫叫。乌苏娜就想起,菲兰达这一天所做的唯一不同的事儿,是把孩子床上的褥垫拿出去晒,因为昨夜在孩子床上发现了臭虫。因为收拾房间时孩子们在场,乌苏娜就以为菲兰达准把戒指放在孩子们唯一够不着的地方——隔板上。恰恰相反,菲兰达却在平常来来去去的地方寻找戒指,不知道正是日常的习惯使她难以找到失去的东西。

抚养和教育霍·阿卡蒂奥的事,也帮助乌苏娜知道了家中发生的甚至最小的变化。譬如,只要听见阿玛兰塔在给卧室里的圣像穿衣服,她就马上假装教孩子识别颜色。

“看,”她向孩子说,“现在告诉我吧:天使拉斐尔的衣服是啥颜色呀?”

背景阅读

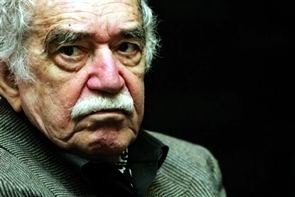

作者简介:

加西亚·马尔克斯(1927一)哥伦比亚作家,记者。生于马格达莱纳省阿拉卡塔卡镇。父亲是个电报报务员兼顺势疗法医生。他自小在外祖父家中长大。外祖父当过上校军官,性格善良、倔强,思想比较激进;外祖母博古通今,善讲神话传说及鬼怪故事,这对作家日后的文学创作有着重要的影响。

加西亚·马尔克斯作品的主要特色是幻想与现实的巧妙结合,以此来反映社会现实生活,审视人生和世界。重要作品有长篇小说《百年孤独》(1967)《家长的没落》(1975)、《霍乱时期的爱情》(1985)等。

本书简介:

《百年孤独》内容复杂,人物众多,情节离奇,手法新颖。马尔克斯在书中溶汇了南美洲特有的五彩缤纷的文化。他通过描写小镇马孔多的产生、兴盛到衰落、消亡,表现了拉丁美洲令人惊异的疯狂历史。小说以“汇集了不可思议的奇迹和最纯粹的现实生活”荣获1982年诺贝尔文学奖。

创作历程:

从1830年至十九世纪末的70年间,哥伦比亚爆发过几十次内战,使数十万人丧生。本书以很大的篇幅描述了这方面的史实,并且通过书中主人公带有传奇色彩的生涯集中表现出来。政客们的虚伪,统治者们的残忍,民众的盲从和愚昧等等都写得淋漓尽致。作家以生动的笔触,刻画了性格鲜明的众多人物,描绘了这个家族的孤独精神。在这个家族中,夫妻之间、父子之间、母女之间、兄弟姐妹之间,没有感情沟通,缺乏信任和了解。尽管很多人为打破孤独进行过种种艰苦的探索,但由于无法找到一种有效的办法把分散的力量统一起来,最后均以失败告终。这种孤独不仅弥漫在布恩迪亚家族和马孔多镇,而且渗入了狭隘思想,成为阻碍民族向上、国家进步的一大包袱。

作家写出这一点,是希望拉丁美洲民众团结起来,共同努力摆脱孤独。所以,《百年孤独》中浸淫着的孤独感,其主要内涵应该是对整个苦难的拉丁美洲被排斥现代文明世界的进程之外的愤懑[mèn]和抗议,是作家在对拉丁美洲近百年的历史、以及这块大陆上人民独特的生命力、生存状态、想象力进行独特的研究之后形成的倔强的自信。这个古老的家族也曾经在新文明的冲击下,努力的走出去寻找新的世界,尽管有过畏惧和退缩,可是他们还是抛弃了传统的外衣,希望溶入这个世界。可是外来文明以一种侵略的态度来吞噬这个家族,于是他们就在这样一个开放的文明世界中持续着“百年孤独”。作者表达着一种精神状态的孤独来批判外来者对拉美大陆的一种精神层面的侵略,以及西方文明对拉美的歧视与排斥。“羊皮纸手稿所记载的一切将永远不会重现,遭受百年孤独的家族,注定不会在大地上第二次出现了。” 作者用一个毁灭的结尾来表达了自己深深的愤懑。