(单词翻译:单击)

名著阅读

José Arcadio Buendía did not know exactly when his hands regained the useful strength with which he used to pull down horses. He grabbed Don Apolinar Moscote by the lapels and lifted him up to the level of his eyes.

"I'm doing this," he said, "because I would rather carry you around alive and not have to keep carrying you around dead for the rest of my life."

In that way he carried him through the middle of the street, suspended by the lapels, until he put him down on his two feet on the swamp road. A week later he was back with six barefoot and ragged soldiers, armed with shotguns, and an oxcart in which his wife and seven daughters were traveling. Two other carts arrived later with the furniture, the baggage, and the household utensils. He settled his family in the Hotel Jacob, while he looked for a house, and he went back to open his office under the protection of the soldiers. The founders of Macondo, resolving to expel the invaders, went with their older sons to put themselves at the disposal of José Arcadio Buendía. But he was against it, as he explained, because it was not manly to make trouble for someone in front of his family, and Don Apolinar had returned with his wife and daughters. So he decided to resolve the situation in a pleasant way.

Aureliano went with him. About that time he had begun to cultivate the black mustache with waxed tips and the somewhat stentorian voice that would characterize him in the war. Unarmed, without paying any attention to the guards, they went into the magistrate's office. Don Apolinar Moscote did not lose his calm. He introduced them to two of his daughters who happened to be there: Amparo, sixteen, dark like her mother, and Remedios, only nine, a pretty little girl with lily-colored skin and green eyes. They were gracious and well--mannered. As soon as the men came in, before being introduced, they gave them chairs to sit on. But they both remained standing.

"Very well, my friend," José Arcadio Buendía said, "you may stay here, not because you have those bandits with shotguns at the door, but out of consideration for your wife and daughters."

Don Apolinar Moscote was upset, but José Arcadio Buendía did not give him time to reply. "We only make two conditions," he went on. "The first: that everyone can paint his house the color he feels like. The second: that the soldiers leave at once. We will guarantee order for you." The magistrate raised his right hand with all the fingers extended.

"Your word of honor?"

"The word of your enemy," José Arcadio Buendía said. And he added in a bitter tone: "Because I must tell you one thing: you and I are still enemies."

The soldiers left that same afternoon. A few days later José Arcadio Buendía found a house for the magistrate's family. Everybody was at peace except Aureliano. The image of Remedios, the magistrate's younger daughter, who, because of her age, could have been his daughter, kept paining him in some part of his body. It was a physical sensation that almost bothered him when he walked, like a pebble in his shoe.

霍·阿·布恩蒂亚甚至没有发觉,他的双手刹那问又有了年轻人的力气,从前他靠这种力气曾把牲口按倒在地,他一把揪住阿·摩斯柯特的衣领,把他举到自己眼前。

“我这么做,”他说,“因为我认为我已到了余年,与其拖一个死人,不如花几分钟拖一个活人。”

就这样,他把悬在衣领上的阿·摩斯柯特先生沿着街道中间拎了过去,在马孔多到沼泽地的路上他才让他双脚着地。过了一个星期,阿·摩斯柯特又来了,带着六名褴褛、赤足、持枪的士兵,还有一辆牛车,车上坐着他的妻子和七个女儿。随后又来了两辆牛车,载着家具、箱子他和其他家庭用具。镇长暂时把一家人安顿在雅各旅店里,随后找到了房子,才在门外安了两名卫兵,开始办公,马孔多的老居民决定撵走这些不速之客,就带着自己年岁较大的几子去找霍·阿·布恩蒂亚,希望他担任指挥。可是霍·阿·布恩蒂亚反对他们的打算,因为据他解释,阿·摩斯柯特先生既然跟妻子和女儿一起回来了,在他的一家人面前侮辱他,就不是男子汉大丈夫了。事情应当和平解决。

奥雷连诺自愿陪伴父亲。这时,他已长了尖端翘起的黑胡髭,嗓音洪亮,这种嗓音在战争中是会使他大显威风的。他们没带武器,也没理睬卫兵,径直跨进了镇长办公室,阿·摩斯柯特先生毫不慌乱。他把他们介绍给他的两个女儿;她们是偶然来到办公室的:一个是十六岁的安芭萝,象她母亲一样满头乌发,一个是刚满九岁的雷麦黛丝,这小姑娘挺可爱,皮肤细嫩,两眼发绿。姐妹俩都挺文雅,很讲礼貌。布恩蒂亚父子两人刚刚进来,她俩还没听到介绍,就给客人端来椅子。可是他们不愿坐下。

“好啦,朋友,”霍·阿·布恩蒂亚说,“我们让你住在这儿,但这并不是因为门外站着几个带枪的强盗,而是由于尊敬你的夫人和女儿。”

阿·摩斯柯特张口结舌,可是霍·阿·布恩蒂亚没有让他反驳。“但是我们必须向你提出两个条件,”他补充说。“第一:每个人想把自己的房子刷成什么颜色就是什么颜色。第二:大兵们立即离开马孔多,镇上的秩序由我们负责。”镇长起誓似的举起手来。

“这是真话?”

“敌人的话,”霍·阿·布恩蒂亚说。接着又苦楚地添了一句:“因为我得告诉你一点:你和我还是敌人。”

就在这一天下午,士兵们离开了市镇。过了几天,霍·阿·布恩蒂亚为镇长一家人找到了一座房子。除了奥雷连诺。大家都平静下来。镇长的小女儿雷麦黛丝,就年龄来说,也适于做奥雷连诺的女儿,可是她的形象却留在他的心里,使他经常感到痛苦。这是肉体上的感觉,几乎妨碍他走路,仿佛一块石子掉进了他的鞋里。

背景阅读

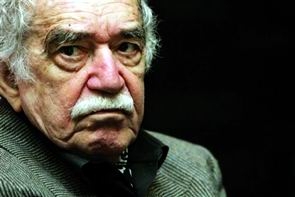

作者简介:

加西亚·马尔克斯(1927一)哥伦比亚作家,记者。生于马格达莱纳省阿拉卡塔卡镇。父亲是个电报报务员兼顺势疗法医生。他自小在外祖父家中长大。外祖父当过上校军官,性格善良、倔强,思想比较激进;外祖母博古通今,善讲神话传说及鬼怪故事,这对作家日后的文学创作有着重要的影响。

加西亚·马尔克斯作品的主要特色是幻想与现实的巧妙结合,以此来反映社会现实生活,审视人生和世界。重要作品有长篇小说《百年孤独》(1967)《家长的没落》(1975)、《霍乱时期的爱情》(1985)等。

本书简介:

《百年孤独》内容复杂,人物众多,情节离奇,手法新颖。马尔克斯在书中溶汇了南美洲特有的五彩缤纷的文化。他通过描写小镇马孔多的产生、兴盛到衰落、消亡,表现了拉丁美洲令人惊异的疯狂历史。小说以“汇集了不可思议的奇迹和最纯粹的现实生活”荣获1982年诺贝尔文学奖。

创作历程:

从1830年至十九世纪末的70年间,哥伦比亚爆发过几十次内战,使数十万人丧生。本书以很大的篇幅描述了这方面的史实,并且通过书中主人公带有传奇色彩的生涯集中表现出来。政客们的虚伪,统治者们的残忍,民众的盲从和愚昧等等都写得淋漓尽致。作家以生动的笔触,刻画了性格鲜明的众多人物,描绘了这个家族的孤独精神。在这个家族中,夫妻之间、父子之间、母女之间、兄弟姐妹之间,没有感情沟通,缺乏信任和了解。尽管很多人为打破孤独进行过种种艰苦的探索,但由于无法找到一种有效的办法把分散的力量统一起来,最后均以失败告终。这种孤独不仅弥漫在布恩迪亚家族和马孔多镇,而且渗入了狭隘思想,成为阻碍民族向上、国家进步的一大包袱。

作家写出这一点,是希望拉丁美洲民众团结起来,共同努力摆脱孤独。所以,《百年孤独》中浸淫着的孤独感,其主要内涵应该是对整个苦难的拉丁美洲被排斥现代文明世界的进程之外的愤懑[mèn]和抗议,是作家在对拉丁美洲近百年的历史、以及这块大陆上人民独特的生命力、生存状态、想象力进行独特的研究之后形成的倔强的自信。这个古老的家族也曾经在新文明的冲击下,努力的走出去寻找新的世界,尽管有过畏惧和退缩,可是他们还是抛弃了传统的外衣,希望溶入这个世界。可是外来文明以一种侵略的态度来吞噬这个家族,于是他们就在这样一个开放的文明世界中持续着“百年孤独”。作者表达着一种精神状态的孤独来批判外来者对拉美大陆的一种精神层面的侵略,以及西方文明对拉美的歧视与排斥。“羊皮纸手稿所记载的一切将永远不会重现,遭受百年孤独的家族,注定不会在大地上第二次出现了。” 作者用一个毁灭的结尾来表达了自己深深的愤懑。