(单词翻译:单击)

You've seen graffiti.

想必大家都见过涂鸦吧。

It ranges from elaborate murals ...to crude scribbles on bathroom walls.

从精致的壁画......到厕所门上那种粗糙的涂鸦。

Leaving your name, or "tag," on things that aren’t yours is an age-old practice in bragging rights – just to say, "I was here."

在不属于你的东西上留下你的名字或“记号”是一种由来已久的吹牛做法了——你不过是为了表达,“我来过这里。”

And the more intricate the tag or more challenging the spot, the better.

而且,你留下的记号越复杂地方越刺激越好

But, this story isn’t about the type of tag you’ve probably seen.

不过,我们今天要讲的这个故事和你们可能看到过的那些记号无关。

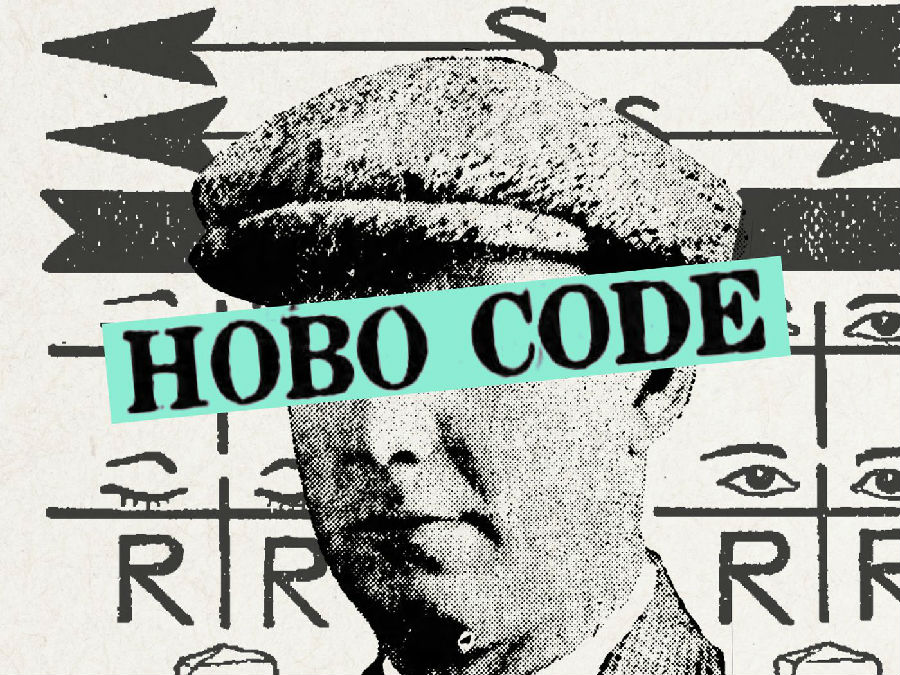

It’s about this one.

我们要讲的是这个记号。

The tag of the hobo.

这个流浪汉记号。

Hobos, or "tramps," were workers and wanderers that once roamed the countryside by illegally hopping freight trains.

“流浪汉”或“流浪汉”就是过去通过非法跳货运火车游荡在乡间的工人和流浪者。

Peak Hobodom in America began in the 1890s, continued through the 1930s,

美国的流浪汉高峰时期始于19世纪90年代,一直持续到20世纪30年代,

and usually coincided with periods of financial crisis and mass unemployment.

通常也是出现金融危机和大规模失业的时期。

Around the same time, the expansion of the railroad opened up new work opportunities in the West.

大约在同一时间,铁路的扩张在美国西部开辟了新的工作机会。

This kind of classic late 19th century hobo was someone who kind of navigated between jobs and not having jobs.

典型的19世纪晚期流浪汉是一种介于有工作和没工作之间的人。

You know, a lot of these jobs are temporary,

大家都知道,这种工作很多都是临时性的,

like seasonal agricultural work, or you know, "Thanks for building the bridge, now get out of here."

比如季节性的农活,或者,“感谢你们帮忙修了这座桥,好了,现在你们可以走人了。”

I’m Bill Daniel, I’m a photographer – I work in film, photo, and tall tales.

我是比尔·丹尼尔,我是一名摄影师 - 我从事电影拍摄和照片拍摄工作,还讲一些夸张的故事。

By 1911, the number of hobos in America was estimated at 700,000.

据估计,1911年美国的流浪汉人数为70万。

Being on the road wasn’t easy.

流浪的生活不容易。

Hobos were unwelcome in many towns and were constantly chased by both local police and private railroad police.

很多城镇都不欢迎他们,当地的警察和私人铁路警察也会赶他们走。

And despite their reputation for being bums, 100 years ago, a skilled hobo was called a "professional," or, "profesh."

尽管100年前流浪还是一件受人尊敬的事,那时,经验丰富的流浪汉还被称为“专家”。

So a profesh is someone who’s, like, good at what they do,

专家就是对自己所做的事很在行的人,

they’re able to not get caught by the law, and you know, leave the camp clean for the next guy.

他们擅长钻法律的空子,还会原封不动地将帐篷留给下一个人。

And maybe most importantly, they didn’t draw attention to wherever hobos were.

也许,最重要的是,他们不会引起人们的注意,去关注流浪汉在哪里。

A profesh, you know, does not blow up the spot.

专业的流浪汉是不会只顾自己的。

Hobos were constantly on the move, but they found a way to communicate with each other — through graffiti.

流浪汉一直在路上,但他们找到了一种相互沟通的方式 - 通过涂鸦。

Search "hobo graffiti" online, and you’ll find these mysterious icons

上网搜“流浪者涂鸦”,就会弹出来这些神秘的图标,

that hobos supposedly used as a sort of coded graphic language.

据说是流浪者们用的一种编码图形语言。

Symbols that they would scratch or draw onto houses and fence posts

他们会在墙上或者篱桩上留下这些标记,

to let fellow wanderers know things like "kind lady lives here," "there are thieves about," or "good place for a handout."

告诉其他流浪者“这家的女主人很善良”,“附近小偷出没,”或“讨吃的的好地方”云云。

Stories surrounding these signs have been circulating for a long time.

长期以来,一直有围绕这些标记的故事流传。

Tramps have a sort of touch-and-go code.

他们有一种类似代码的语言。

This sign, for instance, means "no good."

比如,这个标志的意思是“没必要”。

They show up in the original hobo literature, too.

原版的流浪汉文学中也有这些符号。

Like in the books of Leon Ray Livingston, also known as A-No.1, once the world’s most famous hobo.

比如曾经最为著名的流浪汉Leon Ray Livingston,也即A-No.1 的作品。

In the early 20th century, A-No.1 published several books about hobo life and lore, and included symbols like these.

二十世纪早期,他出版了几本关于流浪汉生活和传说的书籍,书中就有这些符号。

And news articles at the time even claim to decode the "secret hobo language."

当时的新闻甚至声称要解读那些“流浪汉密语”。

This St. Louis Star article from 1921 even includes illustrations of how the signs were supposedly being used.

这篇1921年刊在《圣路易斯之星》上的文章甚至还收录了这些标志使用说明的插图。

The problem is, all this information came from hobos,

问题是,所有这些信息都来自于流浪汉,

a group that took pride in their elusiveness and embellished storytelling.

而他们又是一个以神出鬼没,夸夸其谈为荣的群体。

The truth is, there really isn’t any evidence that these signs were as widely used as the literature suggests.

事实上,没有任何证据表明,这些标记应用得像文献所说的那样广泛。

It’s hard for us to know what the facts were because I think hobos used their mythology as kind of a cover.

我们很难弄清事实,因为在我看来,流浪汉是在用他们的神话作为一种掩饰。

And so the tall tales, and the drawings,

那些离奇的故事,那些图画也是如此,

and even the books by A-No.1 were ways to project an image of themselves that both kind of, like, blew them up, but also kind of kept them hidden.

就连A-No.1的书都是为了把他们的形象塑造得既有一些夸张的成分, 又能够将他们的真实面貌隐藏起来。

Hobo graffiti was actually rooted in a graphic representation of their road persona, called a "moniker."

流浪者涂鸦实际上是从用符号代表他们常年漂泊的形象,即使用“代号”这一做法引申而来的。

Any hobo has a moniker that rides the rails. And different monikers fit different ’bos.

每一个扒火车的流浪者都有一个代号。不同的代号对应不同的流浪者。

Monikers usually said something about the person. Where they were from. A physical trait. If they were young or old.

这种代号通常也说明了那个人的身份。来自哪里?体型如何?年轻还是年长?

How hobos used their monikers sort of falls into two camps:

流浪汉在使用他们的代号时大致可以分为两类:

leaving their tag on boxcars moving across the country, and something Bill calls "tramp writing."

一类人将他们的代号留在全国各地的棚车上,另一类就是比尔所说的进行“流浪汉写作”的人。

Early original tramp writing has to do with addressing the issues of mobility and travel –

早期的独创性流浪汉写作与解决流动和旅行问题有关 -

announcing your place and direction and where you are.

告知你的所在地,方向以及你所处的位置。

The original graffiti included arrows and letters indicating which direction that hobo was heading next.

原创性涂鸦包括说明流浪汉接下来准备去哪里的箭头和字母。

Sort of like a hobo tracker.

有点儿流浪汉追踪仪的意思。

Tramps are generally making these marks on water tanks or stationary things, you know, where they were camped out.

流浪者通常会把这些标记留在水箱或固定物上,也就是他们野营的地方。

So it worked as kind of a personal telegraph. You know, like, "I’m here, you know, is anybody around?"

所以,这种符号差不多起到了个人电报的作用。你懂的,好像在说,“我在这里,附近有人吗?”

Tinder for tramps.

这些符号对他们来说就像是一个燎原的火种。

And it wasn’t long before the drawings moved from stationary objects like water tanks to railcars.

不久之后,这些原本只留在水箱等固定物体上的记号开始转移到了火车车厢上。

I think there was just an evolution,

我觉得这只是一种变化,

kind of like what happened in New York, with, like,

跟在纽约发生的事情差不多,好像是在说,

"Oh I can write on my street corner, but if I write on this train, boom! it’s going everywhere."

“啊,与其在街角涂鸦,倒不如在火车上涂鸦的话,涂在火车上我的涂鸦就会变得到处都是呢。”

And hobos weren’t the only ones doing this kind of graffiti.

而且,流浪汉并不是唯一涂这种涂鸦的人。

Rail workers, stuck in the same trainyard for years, marked passing boxcars with monikers of their own.

多年来,一直停留在同一个火车站的铁路工人,也在用自己的外号标记来往的箱子。

I started doing it October of ‘68.

我从1986年10月就开始干这个了。

A lot of them guys would go on vacation, and they’d say,

很多人都会去度假,

and they'd say "Well I seen one of your damn drawings in Canada, or Mexico, or California, you know?"

他们就会跟我说“我去,我在加拿大,或者墨西哥,或者加州都看到了你小子的涂鸦了,你知道吗?

I thought well, I’ll never get there, might as well send something.

我就想,我恐怕是这辈子也去不了那些地方了,那我不妨派点儿东西代表我去好了。

Monikers aren’t used for communication anymore, but they do still exist in freight graffiti.

人们现在已经不用记号来交流了,但货物涂鸦依然存在。

And it’s kind of come to mean specifically this type of drawing.

而且基本上仅限于这一种涂鸦了。

You know, usually oil stick or chalk-based drawing that’s usually an identity proclamation,

通常是用油画棒或粉笔画的涂鸦,

usually a sketch, a lot of times a self portrait.

通常都是一副速写画,而且很多时候都是自画像。

Moniker just kind of is the perfect word to describe this type of art writing."

代号恰好就是描述这种艺术写作的那个完美的词汇。

At its core, all graffiti is a messaging system, even if the message is as simple as "I was here."

从本质上来讲,所有的涂鸦都是一个消息系统,即便传达的只是“我在这里”这样简单的信息。

Tramp writing, you know, tramp marking, has that in common with graffiti

流浪汉写作,流浪汉记号和涂鸦有一个共同之处,

that it has a little bit to do with making a connection with somebody in a really remote place, even when they’re not there.

那就是它们都和与在遥远的某个地方的某人建立某种联系有点关系,即使他们并不在那里。

Just this ability to say, like, "Whoa, you got here too."

只是能够表达,“哇,你也来过这里耶。”之类的意思。