(单词翻译:单击)

How do you find a dinosaur? Sounds impossible, doesn't it? It's not.

你能找到恐龙吗?听起来不可思议,不是吗?其实并不难。

And the answer relies on a formula that all paleontologists use. And I'm going to tell you the secret.

古生物学家都会用到的一个公式可以帮助我们找到。而且我将会告诉你这个秘密。

First, find rocks of the right age. Second, those rocks must be sedimentary rocks.

首先,找到相应年代的岩石。第二点需要注意的是,这些岩石必须是沉积岩。

And third, layers of those rocks must be naturally exposed. That's it.

然后,岩石表面需要自然暴露在外。就这些。

Find those three things and get yourself on the ground, chances are good that you will find fossils.

满足这三点,你就可以开始了。找到化石的可能性还是很大的。

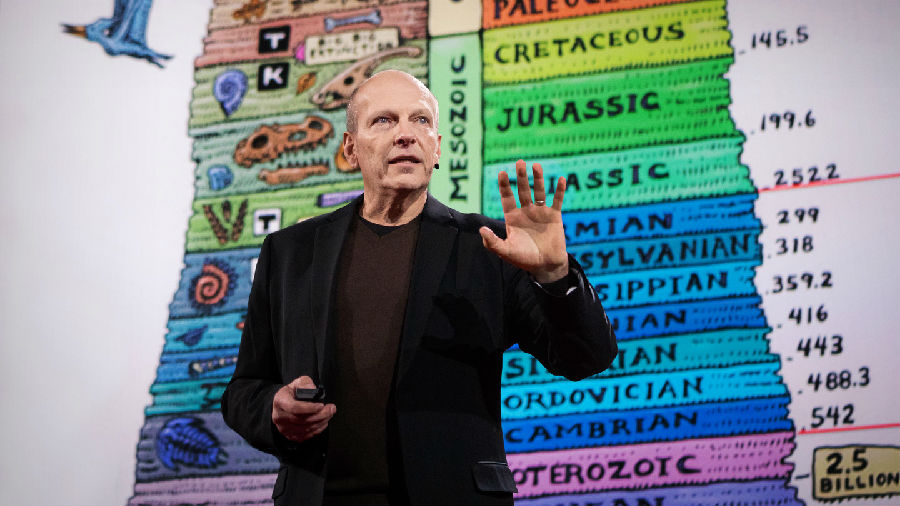

Now let me break down this formula. Organisms exist only during certain geological intervals.

接下来,咱们来具体分解一下这个公式。生物只在特定的地质间隔时期存活。

So you have to find rocks of the right age, depending on what your interests are.

因此你必须找到特定时期的岩石。这取决于你的兴趣。

If you want to find trilobites, you have to find the really, really old rocks of the Paleozoic

如果你想要找三叶虫,那你必须找非常古老的古生代地层岩石,

rocks between a half a billion and a quarter-billion years old.

年龄在5到2.5亿年间。

Now, if you want to find dinosaurs, don't look in the Paleozoic, you won't find them. They hadn't evolved yet.

那么问题来了,如果你想找到恐龙,别去看古生代的岩石,那里找不到。恐龙还没有演化呢。

You have to find the younger rocks of the Mesozoic, and in the case of dinosaurs, between 235 and 66 million years ago.

你需要去找中生代的岩石,并且是有恐龙存活的年代,大概是2.35亿至6600万年前。

Now, it's fairly easy to find rocks of the right age at this point, because the Earth is, to a coarse degree, geologically mapped.

目前找这些岩石还是挺容易的,因为我们已有了地球的大致地理地质面貌。

This is hard-won information. The annals of Earth history are written in rocks,

这可不是个简单的工程。地球的编年史可以说是由岩石写成的,

one chapter upon the next, such that the oldest pages are on bottom and the youngest on top.

一章接着一章,也就是说最久远的在最底层,年代最近的位于表面。

Now, were it quite that easy, geologists would rejoice. It's not.

然而,如果又真的这么简单,地理学家会欣喜若狂了。其实并不简单。

The library of Earth is an old one. It has no librarian to impose order.

地球像是一个古老的图书馆。并没有管理员来为每一本书排序。

Operating over vast swaths of time, myriad geological processes offer every possible insult to the rocks of ages.

来管理如此大范围的时代,无数的地质进程又可能对岩石年龄的判断带来不利影响。

Most pages are destroyed soon after being written.

地理编年史中的书页,大多数也许刚被写成就遭到毁灭。

Some pages are overwritten, creating difficult-to-decipher palimpsests of long-gone landscapes.

有些书页又有重复,对早前的年代做了难解的重叠赘述。

Pages that do find sanctuary under the advancing sands of time are never truly safe.

在时间的流逝中找到庇护的历史,永远不是那么安全。

Unlike the Moon -- our dead, rocky companion -- the Earth is alive,

和月亮这样没有生命的顽石不同,地球是活的,

pulsing with creative and destructive forces that power its geological metabolism.

同时具备创造和毁灭的力量给了他生命,也促进其地质的新陈代谢。

Lunar rocks brought back by the Apollo astronauts all date back to about the age of the Solar System.

月球上的岩石由阿波罗宇航员带回,一直追溯到太阳系的年岁。

Moon rocks are forever. Earth rocks, on the other hand, face the perils of a living lithosphere.

月亮上的岩石是永恒的,而地球上的岩石

All will suffer ruination, through some combination of mutilation, compression, folding, tearing, scorching and baking.

在经历了撞击、压缩、折叠、撕裂和高温的作用后都会遭到破坏。

Thus, the volumes of Earth history are incomplete and disheveled.

因此,纵观地球历史是不完整而且是散乱的。

The library is vast and magnificent -- but decrepit.

地球这个图书馆年代久远而且藏书丰富。

And it was this tattered complexity in the rock record that obscured its meaning until relatively recently.

而且,岩石记录的复杂又使之丧失了原本的意义。

Nature provided no card catalog for geologists -- this would have to be invented.

大自然并没有为地理学家留下任何记录,而是让他们去总结。

Five thousand years after the Sumerians learned to record their thoughts on clay tablets,

在苏美尔人学着在岩土上记录想法的五千年后,

the Earth's volumes remained inscrutable to humans.

地质史对于人类来说还是高深莫测。

We were geologically illiterate, unaware of the antiquity of our own planet and ignorant of our connection to deep time.

我们可以说对地理其实是一无所知,对地球的古老也是一知半解,并对我们与“久远时间”的联系很无知。

It wasn't until the turn of the 19th century that our blinders were removed,

直到19世纪的到来,我们的无知才渐渐消失,

first, with the publication of James Hutton's "Theory of the Earth,"

首先,James Hotton所著的《地球理论》

in which he told us that the Earth reveals no vestige of a beginning and no prospect of an end;

向我们揭示了地球的初始毫无痕迹,终结也会毫无预兆。

and then, with the printing of William Smith's map of Britain, the first country-scale geological map,

随着William Smith绘制了第一张国家疆域范围的英国地图,

giving us for the first time predictive insight into where certain types of rocks might occur.

我们得以预见哪里会有特定年代的岩石。

After that, you could say things like, "If we go over there, we should be in the Jurassic,"

由此,你可以这样说:“我们去那儿能找到侏罗纪”,

or, "If we go up over that hill, we should find the Cretaceous."

“爬过这座山我们能找到白垩纪”。

So now, if you want to find trilobites, get yourself a good geological map and go to the rocks of the Paleozoic.

好吧,如果你现在想找三叶虫,先要有一张好的地图,寻找古生代的岩石。

If you want to find dinosaurs like I do, find the rocks of Mesozoic and go there.

如果你想像我一样去寻找恐龙的痕迹,那就先去找中生代的岩石。

Now of course, you can only make a fossil in a sedimentary rock, a rock made by sand and mud.

当然,你只能在沉积岩中找到化石。这种岩石又沙和泥土形成。

You can't have a fossil in an igneous rock formed by magma, like a granite,

岩浆形成的火成岩,比如花岗岩中,就没有化石。

or in a metamorphic rock that's been heated and squeezed. And you have to get yourself in a desert.

那种经受高温和挤压的变质岩里也没有化石。你一定要去沙漠。

It's not that dinosaurs particularly lived in deserts; they lived on every land mass and in every imaginable environment.

不是说恐龙只生活在沙漠,他们生活在每一片大陆和所有可以想的到的环境中。

It's that you need to go to a place that's a desert today, a place that doesn't have too many plants covering up the rocks,

你需要去沙漠的原因是,沙漠中的岩石没有太多植被覆盖,

and a place where erosion is always exposing new bones at the surface.

并且其风蚀能够使岩石暴露于地表。

So find those three things: rocks of the right age, that are sedimentary rocks, in a desert,

所以,去寻找这三样东西吧:特定年代的岩石、沙漠的沉积岩,

and get yourself on the ground, and you literally walk until you see a bone sticking out of the rock.

然后让自己行走在地面上,直到你看到岩石表面有显露出来的骨化石。

Here's a picture that I took in Southern Patagonia. Every pebble that you see on the ground there is a piece of dinosaur bone.

这是一张南巴塔哥尼亚的图片。你现在看到的地上的每一片圆石都是恐龙的骨头。

So when you're in that right situation, it's not a question of whether you'll find fossils or not; you're going to find fossils.

所以当你身处这种环境下,能否找到化石已不再是问题,你一定会找到。

The question is: Will you find something that is scientifically significant?

问题是:你发现的东西是否具有科研价值?

And to help with that, I'm going to add a fourth part to our formula, which is this: get as far away from other paleontologists as possible.

为了帮助理解,我将为这个公式加上第四条。那就是: 离那些古生物学家越远越好。

It's not that I don't like other paleontologists. When you go to a place that's relatively unexplored,

并非我讨厌他们,而是如果你去一个相对未被探索的地方,

you have a much better chance of not only finding fossils but of finding something that's new to science.

你不仅更容易找到化石,而且更有可能为科学带来新发现。

So that's my formula for finding dinosaurs, and I've applied it all around the world.

这就是我的恐龙寻找攻略。我在全世界都使用过。

In the austral summer of 2004, I went to the bottom of South America, to the bottom of Patagonia, Argentina, to prospect for dinosaurs:

在2004夏季,我去到位于南半球南美的最南端,阿根廷的巴塔哥尼亚最南部,去探究恐龙:

a place that had terrestrial sedimentary rocks of the right age, in a desert, a place that had been barely visited by paleontologists.

在那片还未被古生物学家发掘过的沙漠,有特定年代的陆相沉积岩。

And we found this. This is a femur, a thigh bone, of a giant, plant-eating dinosaur.

我们找到了这个。这是一个巨型食草恐龙的股骨。

That bone is 2.2 meters across. That's over seven feet long.

这块股骨有2.2米宽,也就是7尺多长。

Now, unfortunately, that bone was isolated. We dug and dug and dug, and there wasn't another bone around.

遗憾的是,这是现存的唯一一块。我们不停地挖,然而再也没有别的发现。

But it made us hungry to go back the next year for more.

这使得我们来年又再一次踏上这片土地寻找。

And on the first day of that next field season, I found this:

在新探索的第一天,我发现了这个:

another two-meter femur, only this time not isolated, this time associated with 145 other bones of a giant plant eater.

第二块两米的股骨,这不是唯一的发现,我们又发现了145块食草恐龙的化石。

And after three more hard, really brutal field seasons, the quarry came to look like this.

在三次艰苦的现场挖掘后,挖掘现场场变成了这样。

And there you see the tail of that great beast wrapping around me.

你可以看到,这只大型野兽的尾骨在我身边蜷曲。

The giant that lay in this grave, the new species of dinosaur, we would eventually call "Dreadnoughtus schrani."

躺在挖掘现场的这个大型生物,是恐龙的新物种。最后它被命名为“Dreadnoughtus schrani”。

Dreadnoughtus was 85 feet from snout to tail.

Dreadnoughtus从头到尾有85英尺长。

It stood two-and-a-half stories at the shoulder, and all fleshed out in life, it weighed 65 tons.

它站起来肩部有两层半楼这么高,活着的时候身体有65吨重。

People ask me sometimes, "Was Dreadnoughtus bigger than a T. rex?" That's the mass of eight or nine T. rex.

人们有时候问我,它比暴龙大吗?实际上,它有暴龙的8至9倍大。

Now, one of the really cool things about being a paleontologist is when you find a new species, you get to name it.

话说,成为古生物学家很棒的一点是,你可以为发现的新物种命名。

And I've always thought it a shame that these giant, plant-eating dinosaurs

我常常觉得羞愧的是,这些大型的食草恐龙

are too often portrayed as passive, lumbering platters of meat on the landscape.

往往被描绘成笨拙的一大团肉。

They're not. Big herbivores can be surly, and they can be territorial

然而并非如此。大型食草动物是很有领地意识的,

you do not want to mess with a hippo or a rhino or a water buffalo.

你不会想和河马、犀牛或是水牛这样的动物胡来。

The bison in Yellowstone injure far more people than do the grizzly bears.

黄石公园的野牛比灰熊伤的人要多得多。

So can you imagine a big bull, 65-ton Dreadnoughtus in the breeding season, defending a territory?

所以你能想象一个65吨的公牛,在繁殖季节,会怎样保护自己的领土?

That animal would have been incredibly dangerous, a menace to all around, and itself would have had nothing to fear.

它们会难以置信的危险。对于周围都是一种威胁,而它自己则无所畏惧。

And thus the name, "Dreadnoughtus," or, "fears nothing."

所以他才被称为“Dreadnoughtus”,意为“无所畏惧”。

Now, to grow so large, an animal like Dreadnoughtus would've had to have been a model of efficiency.

为了能长到像Dreadnoughtus这样体型的动物,他们生来就就很有效率。

That long neck and long tail help it radiate heat into the environment, passively controlling its temperature.

其长颈和长尾能够散热,间接地调节了自身的体温。

And that long neck also serves as a super-efficient feeding mechanism.

长颈提供了一个极度有效的进食机制。

Dreadnoughtus could stand in one place and with that neck clear out a huge envelope of vegetation,

Dreadnoughtus能够站在原地,用它长长的脖子把一大片植被一扫而光,

taking in tens of thousands of calories while expending very few.

摄入数以万计的卡路里而同时消耗很少。

And these animals evolved a bulldog-like wide-gait stance, giving them immense stability,

这些动物进化为牛头犬似的宽步动物。这样能够有更好的稳定性,

because when you're 65 tons, when you're literally as big as a house, the penalty for falling over is death.

因为如果你有65吨重,并且像房子那么大,摔倒的后果是死亡。

Yeah, these animals are big and tough, but they won't take a blow like that.

没错,这些动物又大又坚硬,但是他们承受不了这样的打击。

Dreadnoughtus falls over, ribs break and pierce lungs. Organs burst.

Dreadnoughtus摔倒后肋骨会断裂并且刺伤肺部,导致器官爆裂。

If you're a big 65-ton Dreadnoughtus, you don't get to fall down in life -- even once.

如果你是一只65吨的Dreadnoughtus,你绝不想摔倒,一次都不。

Now, after this particular Dreadnoughtus carcass was buried and de-fleshed by a multitude of bacteria, worms and insects,

现在,在这只恐龙的躯体被埋葬,肉体被各种细菌和虫类侵蚀之后,

its bones underwent a brief metamorphosis, exchanging molecules with the groundwater and becoming more and more like the entombing rock.

它的骨头会变质,和地下水进行分子交换,变得越来越接近埋葬它的石头。

As layer upon layer of sediment accumulated,

当一层一层的沉积岩慢慢积累,

pressure from all sides weighed in like a stony glove whose firm and enduring grip held each bone in a stabilizing embrace.

各方面的压力会像石膏套一样向内增压,其坚硬而持久的握力把每块石头牢牢的包裹在内。

And then came the long ... nothing. Epoch after epoch of sameness, nonevents without number.

而后就是旷日持久的虚无。经历了一个又一个纪元,什么都没有发生。

All the while, the skeleton lay everlasting and unchanging in perfect equilibrium within its rocky grave.

恐龙的骨骼在它的石头坟墓里,长久的处于一种恒定不变的、完美平衡的状态。

Meanwhile, Earth history unfolded above.

同时,地球历史也随着展开。

The dinosaurs would reign for another 12 million years before their hegemony was snuffed out in a fiery apocalypse.

恐龙会统治另一个1200万年,直到他们在地球大灾难中灭绝。

The continents drifted. The mammals rose. The Ice Age came.

之后大陆漂移。哺乳动物随之而生。冰河时代来临。

And then, in East Africa, an unpromising species of ape evolved the odd trick of sentient thought.

然后,在东非,一种看来没出息的猿类出奇地在有情思维中进化出来。

These brainy primates were not particularly fast or strong.

这些聪明的灵长类并非特别快速或强壮。

But they excelled at covering ground, and in a remarkable diaspora surpassing even the dinosaurs' record of territorial conquest,

但它们擅长占领土地,并利用出色的散居的方式,超越恐龙征服领土的纪录,

they dispersed across the planet, ravishing every ecosystem they encountered,

它们分布在地球每一处,强占了每一个遇到的生态系统,

along the way, inventing culture and metalworking and painting and dance and music and science

在过程中,它们创造出文化、金工、绘画、舞蹈、音乐还有科学,

and rocket ships that would eventually take 12 particularly excellent apes to the surface of the Moon.

并用火箭载着12位特别杰出的猿人,飞到月球表面。

With seven billion peripatetic Homo sapiens on the planet, it was perhaps inevitable that

有七十亿人类在地球上来回走动,最终难免会有人

one of them would eventually trod on the grave of the magnificent titan buried beneath the badlands of Southern Patagonia.

踏上在南巴塔哥尼亚贫瘠的地表下的巨兽的坟墓。

I was that ape. And standing there, alone in the desert,

我就是那个猿人。独自站在那片沙漠上,

it was not lost on me that the chance of any one individual entering the fossil record is vanishingly small.

我没有忘记,每个人遇到化石的机会是十分渺小的。

But the Earth is very, very old. And over vast tracts of time, the improbable becomes the probable.

但地球非常的古老。而经过漫长的时间隧道,不可能成为可能。

That's the magic of the geological record.

这就是地理的魔力。

Thus, multitudinous creatures living and dying on an old planet leave behind immense numbers of fossils,

然而,大量的生物在这颗古老的星球上生存、死亡,留下了大量的化石,

each one a small miracle, but collectively, inevitable.

每一个体都是小小的奇迹,但集体而言,则是必然。

Sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid hits the Earth and wipes out the dinosaurs. This easily might not have been.

六千六百万年前,一颗小行星撞击地球,导致恐龙灭绝。再来一次,这很可能不会发生。

But we only get one history, and it's the one that we have. But this particular reality was not inevitable.

我们只有一个历史,就是现在我们所有的。但是这个特定的现实不是必然会发生的。

The tiniest perturbation of that asteroid far from Earth would have caused it to miss our planet by a wide margin.

任何对那颗遥远小陨石施加的微小扰动,也能使它远远的错过地球。

The pivotal, calamitous day during which the dinosaurs were wiped out,

那个关键的、灾难性的恐龙灭绝的日子,

setting the stage for the modern world as we know it didn't have to be.

为现代搭建了一个舞台,即使我们知道这并不必要。

It could've just been another day -- a Thursday, perhaps -- among the 63 billion days already enjoyed by the dinosaurs.

它也可以是另外一天--也许是星期四--在恐龙已经享有的六百三十亿个日子中的一天。

But over geological time, improbable, nearly impossible events do occur.

但是在地理时间中,这不可能的、几乎是不可能的事情,确实发生了。

Along the path from our wormy, Cambrian ancestors to primates dressed in suits,

从虫子,寒武纪的祖先,到穿着正式的人,

innumerable forks in the road led us to this very particular reality.

不可计数的岔路带领我们到了这个独特的处境。

The bones of Dreadnoughtus lay underground for 77 million years.

Dreadnoughtus的骨头在地下沉寂了7700万年。

Who could have imagined that a single species of shrew-like mammal living in the cracks of the dinosaur world

又有谁能想到那种精明的、在恐龙世界的缝隙中生存的哺乳动物,

would evolve into sentient beings capable of characterizing and understanding the very dinosaurs they must have dreaded?

却进化成一种能感知的、有能力去描绘与理解他们曾经害怕的恐龙的生物。

I once stood at the head of the Missouri River and bestraddled it.

我曾经站在密苏里河的源头,然后跨过它。

There, it's nothing more than a gurgle of water that issues forth from beneath a rock in a boulder in a pasture, high in the Bitterroot Mountains.

那只不过是汩汩的、从一块比特鲁特山脉上草地上的石头下流出的水罢了。

The stream next to it runs a few hundred yards and ends in a small pond.

它旁边的小溪只流了几百码,并停在了一个小池塘里。

Those two streams -- they look identical. But one is an anonymous trickle of water, and the other is the Missouri River.

这两条小溪,看上去一模一样。但一条是无名的涓流,但另一条是密苏里河。

Now go down to the mouth of the Missouri, near St. Louis, and it's pretty obvious that that river is a big deal.

现在来到密苏里河在圣路易斯的河口,很明显它是很大一条河。

But go up into the Bitterroots and look at the Missouri, and human prospection does not allow us to see it as anything special.

但是回到比特鲁特山脉,看看密苏里河,人类的眼光不足以让我们看出它有多么特别。

Now go back to the Cretaceous Period and look at our tiny, fuzzball ancestors.

再讲回白垩纪,看看我们渺小、毛球般的祖先。

You would never guess that they would amount to anything special, and they probably wouldn't have, were it not for that pesky asteroid.

你绝不会猜到他们将会特别有出息;若非那块讨厌的陨石,他们应该不会有。

Now, make a thousand more worlds and a thousand more solar systems and let them run. You will never get the same result.

现在,再创造1000个世界、1000个太阳系,让它们运行,你永远不会有同样的结果。

No doubt, those worlds would be both amazing and amazingly improbable,

毫无疑问,它们会很惊人,令人感到不可能的惊人,

but they would not be our world and they would not have our history.

但它们不会是我们的世界,也不会有我们的历史。

There are an infinite number of histories that we could've had.

这里有无穷我们可能经历的历史,

We only get one, and wow, did we ever get a good one.

而我们只能有一个,哇,我们所得到的真好。

Dinosaurs like Dreadnoughtus were real. Sea monsters like the mosasaur were real.

像Dreadnoughtus一样的恐龙是真实存在的。像沧龙一样的水怪也是真的。

Dragonflies with the wingspan of an eagle and pill bugs the length of a car really existed.

有着老鹰般翅膀的蜻蜓和如同汽车般大的虫子,也存在过。

Why study the ancient past? Because it gives us perspective and humility.

为什么要研究古老的过去?因为它让我们展望未来,并学会谦逊。

The dinosaurs died in the world's fifth mass extinction, snuffed out in a cosmic accident through no fault of their own.

恐龙在世界第五次大灭绝中灭亡,它们死于天灾而并非自己的过错。

They didn't see it coming, and they didn't have a choice. We, on the other hand, do have a choice.

它们无法预见灾难的发生,也没得选。另一方面,我们是可以选择的。

And the nature of the fossil record tells us that our place on this planet is both precarious and potentially fleeting.

化石揭露了人类在地球的处境,危机重重,同时可能转瞬即逝。

Right now, our species is propagating an environmental disaster of geological proportions that is so broad and so severe,

目前,人类正大规模传播生态灾难,这是场广泛和严重的全球性灾难,

it can rightly be called the sixth extinction. Only unlike the dinosaurs, we can see it coming.

绝对可以称作第六次大灭绝。但唯一不同于恐龙的是,我们能看到它即将来临。

And unlike the dinosaurs, we can do something about it. That choice is ours. Thank you.

与恐龙不同的是,我们可以做些什么。选择权在我们手里。谢谢。