(单词翻译:单击)

敦煌,它实在是太遥远了,也许正如余秋雨先生所说“它因华美而矜持,它因富有而远藏。它执意要让每一个朝圣者,用长途的艰辛来换取报偿”。

In fact, Dunhuang is the only place in the world where you can admire massive amounts of murals and sculptures that are the heritage of hundreds of years of cultural exchange and cross-influence.

But it is the forgotten part of history – the events and stories that were never recorded in any way – that is most intriguing.

For ten nights, a TV documentary series about the visible and invisible history of Dunhuang aired on CCTV, China's official national TV network.

I got the chance to talk to its director, Zhou Bing, who told me so much about both his documentary and the city that I just have to share it with you here.

Reporter:

One day in 1900, a young Taoist named Wang Yuanlu discovered a cave stuffed with aged silk scrolls.

It is impossible to know exactly how he encountered the cave, but in a letter to the then empress of China, Cixi, the man wrote: "My helpers and I happened to be digging into a hill with hoes, and there it was, this huge cave that contains tens of thousands of ancient scriptures, many of them Buddhist scriptures."

There were once hundreds of man-made caves with colorful murals painted on their inner walls, life-size, miniature and magnified sculptures of both Buddhist gods and believers, and more than 50,000 silk scrolls carrying Buddhist scriptures and secular documents, all accumulated just outside this small town.

But Wang Yuanlu sold about 9,000 scrolls to British expeditor Aurel Stein for a mere 220 pounds, which, according to Stein, was barely enough for one such scroll on the European market.

Following Aurel Stein, flocks of archeologists and looters came to Dunhuang from Britain, India, France and Japan.

They took away a significant part of the Mogao caves, stealing thousands of scrolls and even stripping murals from the walls.

That was how Dunhuang's unfathomable heritage was discovered and exposed - to both admiration and destruction.

It is also the beginning of Zhou Bing's documentary, which shares the same title with the city of Dunhuang.

It is rare for the news channel of CCTV to choose to air a documentary series about history and arts during a prime time slot.

It is even risky, considering that most TV viewers might prefer something more entertaining during the Spring Festival holiday.

But it is not difficult to see why CCTV has such high expectations for the production.

The overall image quality is quite pleasing; there are fascinating three-dimensional animated video footages; the narrator has an intoxicating voice.

But it is the narrative that sets it apart from previous documentaries on the same subject, which Zhou Bing had studied before he started shooting his own.

Zhou Bing: [in Chinese] "I have watched a documentary about Dunhuang's caves, made by an NHK team. What distinguishes my work from theirs is that they focus very much on the caves alone, while my team attempted to present a complete picture of the history and heritage of Dunhuang. To achieve that, we used some dramatic elements to tell the stories."

Instead of showing the history of Dunhuang in a safe, linear way, Zhou Bing decided his documentary should have its own characters, each of them involved with Dunhuang this way or another.

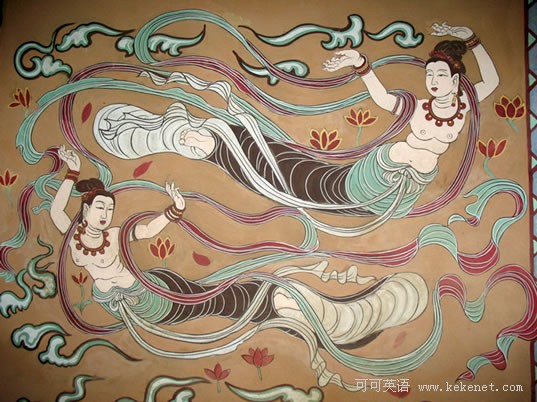

Zhou Bing: [in Chinese] "Most characters are people whose stories were recorded in history books. We also have characters that lived or still live in the modern time, mostly researchers and scholars who devoted their lives to studying and protecting Dunhuang's historical sites. Only one character was fictional. It was a dancer who fled to Dunhuang from the then capital city Chang'an amid a civil war."

The director says the reason he had to make up such a character is he couldn't find a real one in history books, and yet he needed a dancer to fill a blank in the picture.

He feels confident about using the character because historical records show that a coup d'état resulted in a mass immigration of people who served at the imperial court to Dunhuang; among them, many dancers.

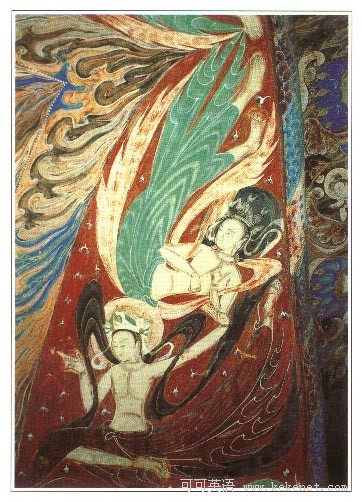

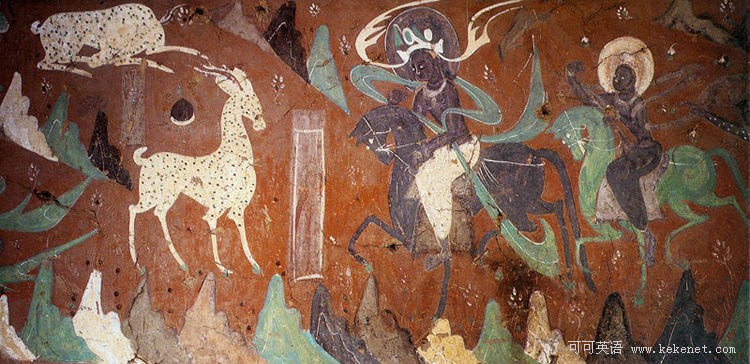

Furthermore, many murals in Dunhuang's caves feature scenes of music and dance performances clearly in the imperial court style.

Still, the director says he stands ready to defend himself against criticism.

Zhou Bing: [in Chinese] "I have braced myself for possible critiques on that, but I have consulted many scholars, domestic and from abroad, and they all assured me that it is a legitimate practice to incorporate fictional characters into a documentary of this nature."

He tells me that he deliberately created a "docudrama," which, just like the structure of the word, means blending documentary and feature film techniques.

Currently, this technique is commonly applied in educational and informative TV productions by prestigious networks such as the iconic Discovery channel of the United States and NHK of Japan.

But 15 years ago in China, it was Zhou Bing and his colleagues who first introduced it to the Chinese TV scene.

With 15 years of experience behind him, Zhou Bing thought he could take the risk of moving one step further.

Zhou Bing: [in Chinese] "Chinese audiences grew accustomed to docudramas years ago. The technique itself is not a novelty. But I took a risk by assigning fictional lines to the characters, something I have never done."

Narrator: [in Chinese] "Ever since her husband's death, Ah-long had not had enough hands to help on her farm. Her farmland went desolate, and the government mistook it for waste land and gave it to her nephew. That changed Ah-long's life."

Ah-long: [in Chinese] "That piece of land by the canal was under my name when I married into the Suo family. Apart from that land, I also got some other properties at that time.

So I had an expensive wedding. If I did not have that piece of land, how could I have had money to throw such a big wedding?"

It may sound too trivial to be included in a serious documentary, but as the director of the International Dunhuang Project, Susan Whitfield, explains, it is more than just a court record.

Susan Whitfield: "We have little windows into ordinary people's lives, and that's what's so exciting, because otherwise those people would have been completely unknown to us."

Seeing actors perform the scene, the audience cannot help but get involved, and according to Zhou Bing, that's exactly what he wants to achieve.

He tells me it was the experience of directing a play - also about Dunhuang's history - that led Zhou Bing to rethink the documentary's potential for being dramatic and interesting.

The 2007 avant-garde play did not fare too well at the box office, but making it inspired Zhou Bing to make his documentary.

Zhou Bing: [in Chinese] "Doing the play led me to think about what really interests people, and I think it is the details of history, not the big picture. For instance, Wang Yuanlu and Aurel Stein were also presented in some of the other documentaries about Dunhuang, but they were just treated as mere names. We, on the other hand, tried to explore the mental activities of them."

The whole first episode of the ten-part documentary series is about the rediscovery of Dunhuang in the early 1900s.

Wang Yuanlu, the self-appointed guardian of the Dunhuang caves, and Aurel Stein, who bought one-fifth of Dunhuang's numerous scrolls for the price of just one, were the focus of the episode.

The director also tells me that he tried not to stereotype the two and pose them simply as the shameless looter and the greedy trafficker.

Instead, he let the characters speak for themselves, and thereby gave them the chance to defend what they did.

This approach is partly inspired by a book by Susan Whitfield entitled Life Along the Silk Road, in which the historian tells the life stories of ten ordinary people who once lived in Dunhuang. Recounting the lives of ten individuals who lived at different times during this period, Whitfield draws on contemporary sources and uses firsthand accounts whenever possible to reconstruct the history of the route through the personal experiences of these characters

Susan Whitfield, director of the International Dunhuang Project, says the paintings of Dunhuang

Susan Whitfield: "She's not in history otherwise. We only know her from history because of this wonderful court case, and the document survived purely by accident, and it was a wonderful opportunity."

The International Dunhuang Project is an ever-growing free online library of information and images of all the manuscripts, paintings, textiles and artifacts from Dunhuang and other archaeological sites along the Eastern Silk Road.

The paintings, she says, are particularly revealing.

Susan Whitfield: "The paintings of Dunhuang tell us a lot; they are the reflections of life at the time, and of people living at the time. And the artists of Dunhuang would draw the things he knew and people he saw. So we can see a lot from that. You get a piece from this part of the picture, and this part of the picture, and another piece here, and then you have to try to imagine, what the whole picture is."

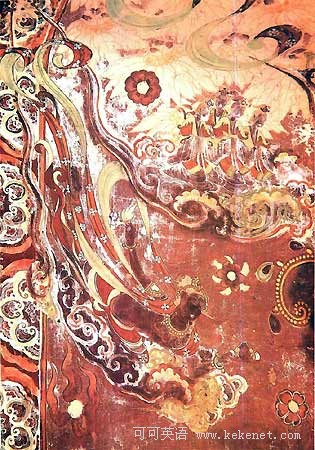

The documentary not only shows many breathtaking paintings from Dunhuang caves that are not open to the public, it also sheds light on how those paintings were probably produced.

Narrator: [in Chinese] "To paint murals, you need very strong shoulders, for you have nothing to rest your elbow on. If your shoulders cannot endure keeping the same position for a long time, your brush will falter… The pigment used by those painters was made of minerals, such as cinnabar, mica and malachite."

Likewise, it also goes to great lengths to explain in plain terms and vivid detail how sculptors worked to produce a huge statue of the Buddha.

Zhou Bing believes that by providing details, the documentary zooms in on the otherwise general account of what happened in Dunhuang during a period of some 1,000 years.

As Susan Whitfield says, it would be hard to imagine the fancy lives people lived in Dunhuang hundreds of years ago had it not been for these paintings.

Susan Whitfield: "They were living in a cosmopolitan city. There were many things to buy, many luxuries, many entertainments, very good music, dance, good restaurants to eat at, very good food to be had, lovely silks to buy, new things coming from abroad. Here you buy goods from all over the world."

But that life has gone, turned to dust, along with the people who once lived it.

As the sea emerged as the easiest way to transport goods, the Silk Road gradually lost its use.

So did the many stops along the road, including Dunhuang, now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Once an oasis located at a religious and cultural crossroads linking Europe, India, and the Far East, Dunhuang finally lost its glow and became the remote, tranquil little city it is now.

Director Zhou Bing tells me that after six years of shooting and production, he finally persuaded himself that maybe Dunhuang was never what we hoped it to be, that maybe it was never such a sensation.

Zhou Bing: [in Chinese] "Dunhuang never was a big place. I looked up the city annals, and found that its population was never more than 200,000. That makes it just a small town."

Yes, there were never many people there, but given the city's history of more than 1,000 years, no one can tell how many people left their footprints there.

The heritage of Dunhuang was built up by every one of those who came to Dunhuang at different times.

Time magnified the city's lost glory countless times over.

With his documentary, Zhou Bing brings the subtle textures of history to light, and thereby allows us to feel the touch of time.