(单词翻译:单击)

5.Not Really My Style

5.不是我的风格

In the middle of our list, we must address a more universal issue than simply how to use "hopefully" or sentence-starting conjunctions. As we've said, English grammar rules are unruly. While we (mostly) agree to follow a (mostly) set list of how to write or speak, we can't discount the myriad exceptions.

在这10个语法规则名单的中间位置,我们列出一个更普遍的问题,这一点要比前面我们提到的“如何使用'有希望地(hopefully)'这个词”或者“以连词开头造句”这种简单问题更普遍。正如我们所说,英语语法规则是难以驾驭的。尽管我们都认可沿用一系列的规则“如何写或说”,但也不得不考虑无数的例外。

Even more troubling: sometimes the exceptions are even accepted and standardized, becoming ... rules. How many times have you fought tooth and nail to prove that correct usage calls for the Oxford (or serial) comma? That's the one that puts a comma after every item in a list, including the one before "and." We hope never. Surely there's something on TV you could watch instead of picking grammar fights. But it's not just a waste of time; it also isn't wrong. The Chicago Manual of Style (which is commonly used in academics and publishing) says serial all the way, but the Associated Press Stylebook (used in journalism or Web copy) says to take that final comma out. The point is that sometimes we confuse "grammar rules" with the style we prefer. If you want to make a scene with someone about their usage, just make sure you're not simply imposing your personal favorite on your adversary.

更麻烦的是:有时候这些例外其实是被允许的或者标准化的,也变成了规则。有多少次你竭尽全力去证明使用“牛津(或系列)逗号”才是正确的语法?“牛津语法”指的是在英语中列举多个对象时,在最后的“和(and)”前也加上一个逗号。我们希望你永远都不要去证明这个问题。电视里总有精彩节目可看,你不一定非要“打语法战”。但是周旋于语法问题也不是纯粹浪费时间,更没什么不对。学术和出版业普遍使用的《芝加哥格式手册》支持使用“系列逗号”,而新闻报道或者网页文案普遍使用的《美联社写作指南》则认为应该把最后一个逗号去掉。关键是,有时我们会把“语法规则”和“语法风格”搞混。如果你想和某个人因为语法问题当众争论,那么请尽量保证不要将自己的个人喜好强加在对方身上。

4.I Could Care Less About Grammar

4.不必那么在意语法

Oh, to be at the grocery store with grammar jerks. Not only are they frowning at every handwritten sign to suss out split infinitives in the weekly sales, but they also refuse to use the express lane. "Ten items or less," they sniff. "Incorrect. Should be 10 items or fewer. Let's get in the other line to protest." You're pretty sure you heard that rule as well, so you hang your head in shame and follow your friend to the next line, behind the guy with 70 coupons and a checkbook. Not anymore. Centuries ago it started to become accepted that less would be used for items that couldn't be counted ("I ate less food," "There should be less contempt for my greed") and that fewer applied to countable objects ("I ate fewer cakes," "There should be fewer mean looks from people about the cakes I did eat"). Unfortunately, this has less to do with an actual "rule" and more to do with the preference of an author, one Robert Baker, that became widely disseminated. So go ahead and jump lines again to get out of the store as fast as possible. Try to lose the rude friend while you're at it.

嘿,跟你的“语法混蛋”朋友去逛超市吧!他们不仅会对“每周特价”标语里被拆分的不定式嗤之以鼻,而且还会拒绝使用超市的快速结算通道。在表达“购买十件商品以内”这句话时,超市会用“less”来形容商品,这些朋友就会抱怨道,“这是错误的,应该是用'fewer'来形容商品,我们去另外一条通道结算以示抗议吧。”你也知道有这么一条语法规则,所以你会羞愧地低下头,跟着朋友排到另一条结账队伍里、排到一个手拿着七折优惠券和支票簿的人后面。可是这样的事情不会再发生了。很久之前,“less”这个词用来形容不可数名词,比如“I ate less food”、“There should be less contempt for my greed”(译为“我饭量变小了”、“人们不该因为我贪食就如此鄙视我”);而“fewer”是用来形容可数名词,比如“I ate fewer cakes”、“There should be fewer mean looks from people about the cakes I did eat”(译为“我很少吃蛋糕”、“人们不该因我爱吃蛋糕就投来如此多的白眼”)。遗憾的是,这已经跟真正的“语法规则”相差甚远,而是跟作家“罗伯特·贝克”的偏好有关,这已经被传得家喻户晓了。所以走吧,重新换一条结账队伍,尽快付钱离开超市吧!如果你也有那种粗鲁的“语法混蛋”朋友,那么甩掉他吧!

3.It's the Sound, Not the Letter

3.是发声导致的错,并不是字母的错

If you're feeling a little shell-shocked about all the grammar rules you thought you knew but don't really, things are looking up: You probably know half of what you should about when to use "a" versus "an."

如果你正被上述这些本以为了解、但事实上不了解的语法规则弄得头晕脑胀,那么现在情况会有所改善:你可能大概了解什么时候该使用“a”和“an”。

Most of us learned (or at least have the vague memory) that we use the article "a" before a consonant and "an" before a vowel. If you're a native English speaker, this probably comes naturally to you, so naturally that you are wondering why it's even on this list. Again, we harken back to exceptions. Sure, when you walk into a restaurant you're going to have to wait "an" hour for a table, but you're going to hear that from "a" hostess. What in the world? It's not the vowel itself that makes the difference; it's the vowel sound. If the word starts with a vowel sound, add an "n" to that "a." If it's a consonant sound, it's an easy "a."

很多时候我们知道(或至少有一个模糊概念)在辅音单词前使用冠词“a”,在元音前使用冠词“an”。如果你母语是英语,这对你来说是一件很自然的事情,自然到你想知道本文为什么会列出这一条语法规则。那就让我们再来看一下这种特例。当你走进一间餐厅,你必须要等一个小时才能有空位子,但是你需要一个服务员来通知你。这究竟是为什么?并不是因为元音本身导致了这种区别,而是因为发元音的音标。如果一个单词的首字母发元音,就要加“an”,如果首个字母发辅音,那就是一个简单的“a”。

2.To Infinitives and Between

2.不定式和中间插入语

While "splitting infinitives" sounds like something Superman would do to save Metropolis, our English teachers might've had us believe that it was only fit for villains.

虽然“分裂不定式”听起来很像是超人拯救城市时会做的伟大举动,但是英语老师让我们相信它只适用于反派人物。

The full infinitive is the "true" form of the verb; that is, the verb without conjugation. To go, to eat, to do, to split an infinitive -- you get the idea. When we talk about splitting infinitives, we mean we stick an adverb in the middle of the full infinitive. To bravely ask. To boldly go. To tediously list. Scandalized, aren't you? How dare we ... put those adverbs there. Exactly. It doesn't sound wrong. But in the 19th century, an English grammar book argued that it wasn't common usage. In addition, you can't split infinitives in Latin since they're one word (currere) rather than two (to run), and Latin was still a big deal back then. Accordingly, people went along with the decree forbidding split infinitives . But it didn't entirely catch on because pesky "common usage" really did win out. We split infinitives, with perfect comprehension, all the time. Now we can choose to keep them together or to split them smugly, knowing we're on the right side of grammar.

带to的不定式是动词的“真正”形式,是没有词形变化的动词。去(某个地方),去吃,去做,去分裂一个不定式——你知道这些不定式的意思。当我们说到分裂不定式时,我们的意思是将一个副词插入到带to的不定式之中。“To bravely ask”、“ To boldly go”、“ To tediously list”(译为“去勇敢地问”、“向前大胆地走”、“沉闷地列出来”),这些表述让人觉得反感,不是吗?我们怎么能把这些副词放在那里呢?的确,它听起来没有什么错误。但是19世纪的一本英语语法书中曾指出,分裂不定式不是习惯用语。此外,拉丁语里的不定式不可分裂,因为在拉丁语中不定式是由一个单词(currere)构成而不是两个单词(to run)。而在那个时代,拉丁语的地位非常重要。因此,人们遵守着禁止分裂不定式这个规则。由于烦人的“习惯用语”说法真的胜出了,分裂不定式没有完全流行起来。但是,我们一直都运用着完美的理解能力来分裂不定式。现在我们知道,不管选择把它们放到一起还是得意地将它们分裂开来,在语法上都没有错。

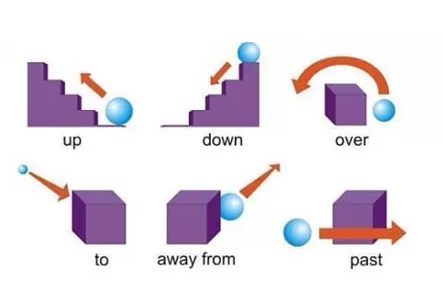

1.Don't Preposition Me

1.不要用介词难倒我

This is a grammar myth that won't die. More specifically, it's a grammar myth that a billion well-meaning know-it-alls won't let die. Ending a sentence with a preposition -- something like "She's not someone I would go to the batting cage with" -- is perfectly fine. The sentence is clear, and no one would argue its structure. (Although why you wouldn't go to the batting cage with someone is more of a mystery. What will she do to you?!)

这是永远不会消失的语法传奇。更具体地说,这是十亿善意的万事通们都不愿让之消失的语法传奇。用一个介词来结束一句话——比如“She's not someone I would go to the batting cage with(译为我不会跟她一起去打棒球的)”——这样是很好的。句子清晰,没有人会质疑它的结构。(尽管为什么你不会和某人去打棒球更像是个谜。她会对你怎样啊?!)

So why do we have this idea that ending a sentence with a preposition makes for an inexpert turn of phrase? It makes sense if you're Julius Caesar but probably doesn't apply to you or me. In Latin, ending a sentence with a preposition really was incorrect. In 1762, an Anglican bishop printed a book of grammar and basically co-opted the Latin rule for English. A good try, but English-speaking peoples had been ending sentences with prepositions for ages, and the practice persisted.

所以,为什么我们会认为用介词结尾的句子看起来很笨拙呢?如果你是凯撒大帝,那么确实会有这样得的想法,但是显然它并不适合你我。在拉丁语里,用一个介词来结束一句话确实是错误的。1762年,英国的圣公会主教出版了一本关于语法的书籍,并为英语制定了拉丁语语法规则。虽然这是一个很好的尝试,但是说英语的人们已经用介词结束句子太久了,他们现在依然延续着这种惯例。

审校:Freya然 编辑:Freya然 来源:前十网